For a brief period of my life, the Hubble Space Telescope would shoot me an email with a link about once every two weeks. Then I would click and wait.

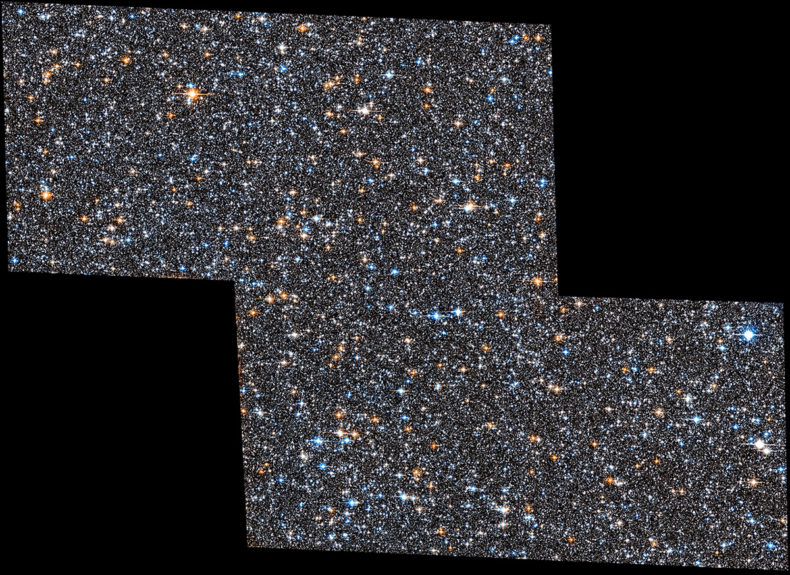

Then hundreds of thousands of stars would spill across my monitor, lighting up cells in my eyes with photons from a screen from a file from silicon chips circling earth behind a giant, almost but not-quite-perfect mirror that had just wrangled together beams of starlight shining from halfway across the galaxy.

I write that now, as a science journalist, with a sense of how cool it was. At the time it felt normal. Just out of college, I had gone to work as a data analyst for Hubble, at the observatory’s science center in Baltimore. One of my smaller responsibilities was to glance over new pictures that one of my bosses was taking of the galactic bulge, the Milky Way’s pudgy, starry midsection.

Here’s how it worked. I would fetch those fresh images obtained up high through an archive system. Then I’d open them up in DS9, a software application that is probably running right now on the desktop of every astronomer in the world. Developed at Harvard in the 90s, it succeeded another program called TNG, and if you don’t get the pattern I honestly just feel sad for you.

With DS9, I could blink* between frames, or fiddle with the grayscale of the images. With one set of parameters, only the brightest stars would pop out from a black screen. With another, you could see the very faintest but still-distinct stars, the kinds of fine details no other piece of technology but Hubble could capture.

Later, our team would try to gauge the brightness of every single star in the image and then measure them waxing and waning over time. Discoveries would hopefully follow. But this was just a quick visual check to make sure nothing had gone wrong with the telescope. After I finished, I would just close the files, stop thinking about it, and go right back to whatever else I had to do.

See, in science, somebody sees the data first. We science writers tell stories that fetishize the eureka moment of knowing, the solitary scene of Moses on the mountain grasping at an underlying truth that has been out there all along. Think Galileo squinting at the specks — moons! — around Jupiter. Or Einstein’s thoughts about gravity suddenly, vertiginously falling into place.

But I’m describing a much lesser moment, the sense of simply experiencing a little unmapped bit of the universe. Like standing at a roadside lookout that no one has ever stopped at before.

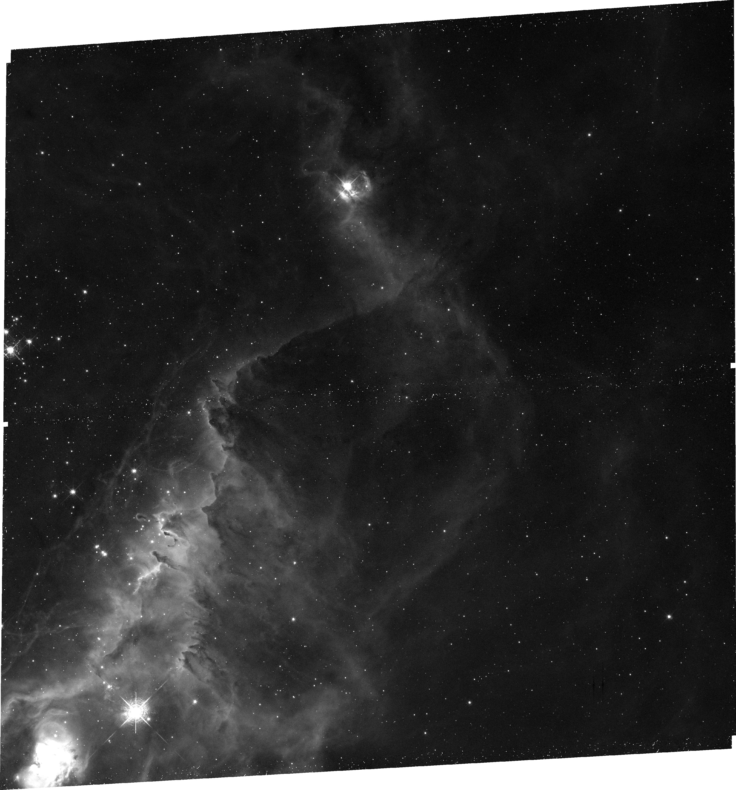

I was reminded of this sensation near the end of April, when NASA began hyping an image to celebrate the 30 year anniversary of Hubble’s launch back in 1990. It turned out ethereal and mind blowing and also about what you’d expect: a photo showing two distant star-forming nebulae, snapped through a few different filters, stitched together, and then rendered in hyperreal hues thanks to a color sensitivity far beyond our own puny eyes.

Losing myself in that image, I thought, “someone saw this first.” Someone got to stand at that vista before anyone else.

First they got the files. Then they probably ogled those wispy clouds full of embedded, difraction-spiked** stars in DS9, gawking at a cosmic still-life that had been posing out there all along, but that nothing except Hubble, looking in this particular way for this particular length of time, could have seen.

I thought about what that might be like. How seeing a little farther out into the black before anyone else, you could feel consuming awe or completely normalized or, most likely, a little bit of both.

And then I remembered, hey, I used to know this. And now, hopefully, you do too.

________

*Blinking between frames means lining up two different images of the same block of sky, then switching back and forth. You notice how well stars align between frames, or if they seem to move or change.

**Stars in pictures often sport a twinkly crosshair pattern, like the big one in the bottom left of the last image. This happens in the telescope through diffraction, from waves of starlight lapping against each other and against the struts that hold up Hubble’s mirrors. (Also notice the vertical spikes around that same star, which happen when a star is so bright that its signal bleeds into other pixels in the same column.)

_________

Bio: I’m an award-winning independent freelance science writer. I like things like planets and fossils, plus the scientific systems we’ve built around studying them. Based in Boston, I sometimes walk over to talks at MIT and Harvard for stories, but not as much as I should. You can check out my work at joshuasokol.com, or say hi at @josh_sokol.

___________

Photo credits, from top to bottom: the SWEEPS field full of stars by NASA, ESA, A. Calamida and K. Sahu (STScI), and the SWEEPS Science Team; the next two images of giant red nebula (NGC 2014) and its smaller blue neighbor (NGC 2020) by NASA, ESA, and STScI.

I enjoyed this. It’s easy to forget that someone else saw these images in a relatively mundane format. Afterall, someone saw the Grand Canyon first. Thanks for the links. I’ve always wondered what these pictures looked like before all the photo processing and filters and colorizers get applied. A great way to fill some time.

Thanks

The urge to “see things first” drives some truly great discoveries! Thank you for sharing your explorations. (from a former underwater cave explorer and cartographer)