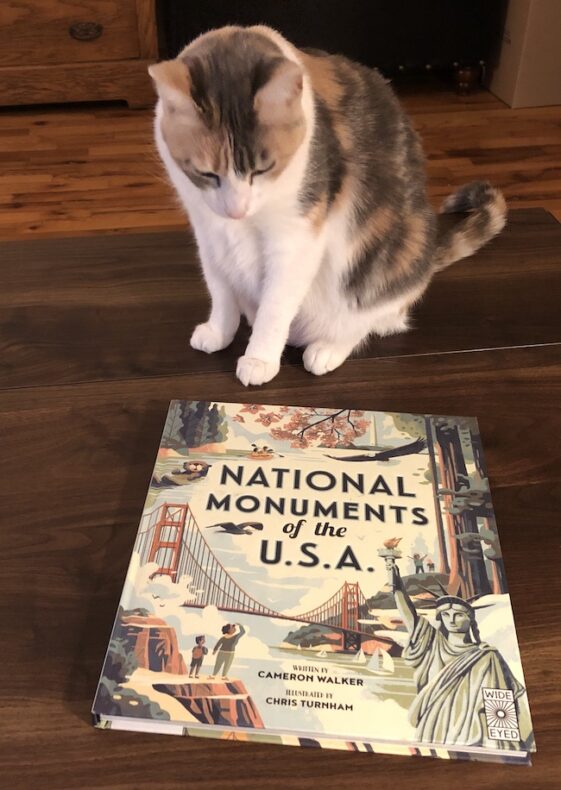

Cameron’s new children’s book, National Monuments of the USA, hadn’t gone to print when she and I met up for tea at the annual science writers conference in Memphis last October. She was still fact-checking and finalizing, and having a (tiny!)(Cameron: big!) freakout about how the book would be received.

To teach history to children isn’t easy, ever. When I read Cameron’s book I understood what a challenge she’d accepted. How to celebrate what’s inspiring and beautiful about America, without blotting out the painful truths many monuments were built to commemorate? We talked about that and other things, now that the book is out and the reviews are in.

Emily: Cameron, how’d this project come about?

Cameron: So my friend Kate Siber, who I met working at Outside magazine many years ago, had done a book about the national parks that has the same wonderful illustrator, Chris Turnham, which had the same format: an introduction, full spreads with illustrations of a selection of the parks, and short write-ups about things to see and do in each park. She had done a few books for the same publisher, and she gave them my name. (Thank you, Kate!)

I learned a lot from this book. There were places I’ve never heard of, especially on the East Coast. Growing up in California — I don’t know what your history and civics education was like — but mine was very, ahem, local.

I feel the same. You probably went to California missions in fourth grade, or things like that? I did, too.

Yes, we made Spanish colonial missions out of sugar cubes. It was weird. Did you visit monuments as part of the writing process? Or was it mostly reported from afar?

A lot of it was reported from afar, because when I started doing the reporting a lot of the monuments were still closed or hard to get to. Once some of the travel restrictions were lifted, I thought, this will be perfect: My kids are being homeschooled, basically. Why don’t we rent an RV and go on a road trip for six months? But as the pandemic continued, I realized, no, my kids really need to be at home and have a steady routine, and I do, too. (Also: renting an RV is expensive!). So we didn’t have our full pandemic road trip, but we did take a short pandemic road trip to see six or seven monuments. We also saw a couple in California on other trips, and I had been to several of the national monuments elsewhere in the past.

Were you talking to the boys about it as you wrote the book? Did they have feedback?

Yeah, they did. They had strong feedback about what they liked and what they didn’t like. And by the end of our road trip, it was like, “Mom, do we really have to go to see another monument?”

I remember talking with one of the boys about Tule Lake National Monument, because he was studying World War II and Japanese incarceration in his history class. I was really having trouble with what language to use [for the camps where Japanese Americans were imprisoned]. We often call them internment camps, but I guess that’s really not correct. Internment camps are for foreign nationals, but most of the people in these camps were U.S. citizens.

These were concentration camps. FDR even said that in memos, his staff said that in memos. But there’s so much feeling about the word “concentration camp” connected with the Holocaust that I wasn’t quite sure what to do. I wanted to use the real word, but also, I didn’t want to stop people in their tracks and have them stop reading and not learn more about Tule Lake because they’re so disturbed by calling these places “concentration camps.” So I was talking to my son about it for a while, and he really got what I was struggling with. At one point, I said, “What if I said they were imprisoned in these camps?” And he thought that was a good solution–saying what was actually happening there.

So that’s what I ended up doing. I also sent the text to a Japanese-American history organization and to the ranger at the site, and so I had background on the camps from them, too, and a sensitivity reader looked at the whole book toward the end of the process. And it was also really great to talk with my son to get the perspective of a kid who’d be reading this.

Do you feel like you learned anything about how to talk to kids about the disturbing history of some of these places?

Yes, through trial and error. Working with the sensitivity reader was really interesting, because there were a lot of things I was concerned about, and was really careful about–and those things didn’t seem to be an issue. But then there were other things that I hadn’t even thought of that the reader pointed out.

One of them was the Statue of Liberty National Monument. When we were choosing which monuments to include, we knew we were going to cover the Statue of Liberty because it’s so iconic. So my initial write-up of the introduction to that monument was about coming to a new land, having a fresh start, and the Statue as a hopeful symbol of all of these things. And the reader said something to the effect of, you really want to recognize that that is just one story of coming to this country. There are all these other immigration stories that didn’t happen that way. And not everyone sees the Statue of Liberty as this great symbol of independence and openness.

And the reader was right. And, also: this book is for kids, and the intention of the book is to introduce them to these places in a way that they’ll feel welcome and curious and want to learn more. So that was a really interesting balance to strike. But having that input from the sensitivity and working to try to address those issues felt good to me.

I really like the mix of culture, people, history, plants, different creatures you include for each monument.

That’s what’s so fun about the national monuments, they are all those things. If you were interested in plants, you could go and just focus on plants. Or you could just focus on history. There’s so much to learn about, wherever you go.

Are there any monuments that you’re dying to go to now?

I really want to go to Jewel Cave, because it sounds so cool. The ranger I talked to said, “You come down, and it’s like stepping into this geode. I was like, “Oh, my gosh, I want to step into a geode! That sounds amazing!”

Would you usually call somebody at the monument for the research?

I called a ranger or an educational specialist at each monument. A lot of the monuments have “Friends of the Monument” groups, so I would call those groups. If there was information about Indigenous people I wanted to include, I’d try to contact that tribal nation or someone who was really familiar with and worked with Indigenous groups in the area. For Katahdin Woods and Waters, I got to talk to a local naturalist who was super cool and knew all about the monument. I love talking to people about the places they love.

Did your perspective on the US change while you were writing this?

Yeah, I think it did. I saw the history as more of an interconnected web instead of, you know — the Civil War —and then — railroads — and then — civil rights, each in a little box. The Pullman Porters were Black men who were recruited for those jobs after Emancipation, so their history is tied to all of those things: the Civil War, railroad history, labor rights, civil rights. And one of the forts in Florida, Castillo de San Marcos National Monument, was a prison camp for Indigenous people who had come from land that’s now a monument in Arizona. All of these things were working together in a way that I didn’t realize.

And of course that’s how it is. Everything’s connected. But it was interesting to see that play out in these monuments. And obviously, all those things are connected to today — we are where we are now because of these things that happened.

What were you afraid people would say about this book? I remember you were originally really worried about the feedback you might get.

Let’s see, I think I was worried about — both with civil rights and Indigenous issues — that I shouldn’t be writing about them as a white person from California. Particularly with the civil rights-related monuments, I felt like an idiot sitting here at my desk making phone calls, trying to take this huge, complicated history and make it really simple for kids.

After I saw you in Memphis, I also went to Alabama to go to both Birmingham Civil Rights and Freedom Riders national monuments. I’m so glad I took those trips, because I felt more confident — not overconfident! — but I felt that it was important that we were talking about these monuments even if I was going to mess up while writing about them. I was at least confident that these are stories that need to be told, even if I might not be the perfect person to tell them.

And of course, kids are a huge part of these monuments already–thousands of children marched in Birmingham for civil rights, and there’s a story of a little girl that helped the Freedom Riders. It was great to be able to celebrate kids as part of writing about these places, and to know they would understand the complexity of these stories, because. They’re more clear-eyed about it than most grownups, I think.

Have you gotten any of the negative feedback you dreaded?

I have not read the Amazon reviews–I’m sure there are negative reviews in there! Chris, the illustrator, posted one of them on Instagram: the reviewer wrote that the book was inappropriate for kids because Stonewall National Monument is in there, and there’s an illustration of a drag queen. But that kind of negative feedback felt different than I thought it would: it just made me feel really glad we did Stonewall. It’s still so relevant today. How could we not include it?

And the positive feedback has really been amazing. I’ve done a couple of events for the book, and each time, people have come up and wanted to tell stories of what the national parks and national monuments meant to them, remembering camping with their families or going to certain places. That was when I realized how much these places mean to so many people, from different backgrounds and different places in the country. One woman was about to join the military, and she was talking about how this is such an important part of the country she loves, having these protected spaces.

Speaking of protected spaces, this summer Biden designated a new monument! The Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni – Ancestral Footprints of the Grand Canyon National Monument, right?

Yeah! And there’s Avi Kwa Ame National Monument, another new one, in Nevada. He’s designated five, so far, in the last year.

Is that a lot by presidential standards?

That’s a good question, who did the most. (Ok, I looked it up: it’s Barack Obama, with 29 national monuments). During the Trump administration there were also five new national monuments, but he did not designate them himself. They were part of a congressional act that he signed. And of course, during that time, the president was also working to reduce the size of several existing national monuments. So it’s definitely a change from those years in the sense that the current president is actively designating these places.

I’d be interested in reading about why presidents have made the choices they did about specific monuments during their administrations.

There’s a great book about national monuments for adults, This Contested Land, that you might like. It’s by McKenzie Long, and it’s a very nuanced, in-depth look at the national monuments. She visits thirteen national monuments in the book and really digs into the political, cultural and environmental history of these places.

That sounds like something our LWON readers would enjoy. Any other monument resources you’d like to share?

Yes! I would like to tell people about a program called Every Kid Outdoors. If you’re in fourth grade, you get free admission to national parks, national monuments, and other federal lands, It’s good for you and your family for the whole year of fourth grade. And you just sign up online ( if anyone needs help signing up, I’m happy to help!). But I think people don’t know about it, and it’s so awesome–I’d love for every fourth grader to know about it!