Some smart cookie timed the release of the movie about Robert Oppenheimer to the week of the anniversary of Trinity, the first test of the first nuclear weapon. (Another smart cookie threw in the release of a Barbie movie and a notable Barbenheimer genre was born, but that’s not what this post is about right now.) Anyway. Oppenheimer’s leadership of the Manhattan Project that led to Trinity is so famous that most of us (me) forget that he also did brilliant — at least for a while — physics. This first ran August 21, 2013, Oppenheimer and Wheeler had both died already, and Dyson has died since. The comments on the original post are probably better than the post.

Physicists, like the ancient Greeks, like to gossip about their gods. Three physicists* happened to be talking on Twitter** about a review by a fourth physicist, Freeman Dyson, of a biography of one of these gods, J. Robert Oppenheimer, and about his war with another one, John Archibald Wheeler.

Physicist #1: Oppenheimer did the breakthrough work on black holes.

Physicist #2: Isn’t it ironic that Wheeler gets credit for inventing black holes?

Physicist #3: Dyson’s review doesn’t talk about Wheeler’s bitter rejection of Oppenheimer’s black holes and Oppenheimer’s antipathy toward Wheeler.

Physicist #2: So interesting. Maybe Oppenheimer wasn’t accustomed to challenges? And then Wheeler invents the phrase, “black hole”, and Oppenheimer never uses it.

Physicist #1: “. . .[the star] like the Cheshire cat, fades from view. One leaves behind only its grin, the other . . .”

Physicist #1: “. . . only its gravitational attraction.” – John Wheeler 1967

Physicist #3: I heard Oppenheimer sat outside the auditorium when Wheeler was giving the talk that conceded that black holes form.

Physicist #2: I remember now, that story is in Kip Thorne’s book***.

Me: Oh my what a story!

Physicist #1: I’d just like to 100% endorse @AnnFinkbeiner’s tracking it all down.

And off I go to find Kip Thorne’s book. And Wheeler’s autobiography. And Dyson’s review. And the Web of Stories online interviews. And to fall thoroughly down the rabbit hole, where it’s dark and lonely but, you know. Interesting.

§

Oppenheimer was called Oppie and Wheeler was called Johnny. They were both so smart that no mere mortal could know how smart they were. Oppenheimer was a show-off and good at it, also restless and impatient; Wheeler talked quietly with pauses so long that every time I interviewed him, I thought he’d gone to sleep. Oppenheimer was personally remote; Wheeler was curious about everyone – “what is your great white hope?” he liked to ask. Oppenheimer looked like he knew things you wouldn’t care to; Wheeler looked blue-eyed and innocent. Oppenheimer was older: Wheeler had considered then decided against being Oppenheimer’s student. They spent much of their careers together, in small-town Princeton, NJ. Kip Thorne says their confrontation was inevitable. Freeman Dyson was there then too, so they all had plenty of chances to get on each others’ nerves

§

On September 1, 1939, Oppenheimer published the theory of how a giant star runs on thermonuclear fusion until it’s out of fuel, then implodes and cuts itself off from the rest of the universe. On the same day, Wheeler published with Niels Bohr the explanation of atomic fission, how an atomic can split apart and release its energy. Also that day, Hitler invaded Poland. Put those last two sentences together and you know what the next sentence has to be.

Before Oppenheimer could follow up on the gravitational cutoff idea, he became head of the Manhattan Project and directed the building of the fission bomb. “In some sort of crude sense which no vulgarity, no humor, no overstatement can quite extinguish,” he said, “the physicists have known sin; and this is a knowledge which they cannot lose.”

Wheeler also paused his pure research and became scientist in charge of producing the bomb’s plutonium fuel at the Manhattan Project’s Hanford plant. While Wheeler was there, he heard that his brother, who was fighting in Italy, was missing in action. “It was a year and a half before his body was found – well, I can’t call it his body – his skull and his skeleton,” he said. “I always think to myself that if I’d only gotten going sooner on making plutonium for a bomb, I could have saved his life.”

By 1949, the Manhattan Project had succeeded, Hiroshima had been flattened, and the next bomb up — the hydrogen bomb that operated not on fission but fusion — was being designed. Wheeler and Edward Teller were in favor of building it and Wheeler, probably with his brother in mind, directed some of the massive design calculations. Oppenheimer was opposed to it: it was sin all over again, could be used only to slaughter civilians, and almost certainly wouldn’t work. Wheeler heard that Oppenheimer had said, “Let Teller and Wheeler go ahead. Let them fall on their faces.” But the calculations showed the design would in fact would work and those calculations, Wheeler wrote, “turned Oppie around.” By 1952, Oppenheimer was saying the hydrogen bomb was so “technically so sweet” that he couldn’t argue with it.

§

One night in January, 1953, Wheeler took some classified documents – violating common sense and every security regulation — to Washington DC on the train. He left his seat and went to the bathroom and when he came back, the documents were gone. He looked everywhere, asked the porter and fellow passengers, no luck. Once the train got to DC, the car was disconnected from the rest of the train and searched, as was the train track from Trenton to DC, as were Wheeler’s home and office. The documents were never found. Wheeler was yelled at by the highest authorities.

The lost documents were on lithium 6, one of the fuels then being considered for the hydrogen bomb and may or may not have also included information about nuclear spying. The documents had been put together by a colleague of a Congressional staffer named Bill Borden. Borden was convinced that some traitor was blocking the plans for using lithium 6 and slowing the development of the hydrogen bomb, and that furthermore, Oppenheimer was probably an agent of the Soviet Union — which he was not. A later story went around that Wheeler’s lost documents helped trigger the cascade of investigations into Oppenheimer’s loyalty. The story is almost certainly purest blue-sky nonsense, but it still floats around and confuses the innocent.

Regardless, in 1954, Oppenheimer was subject to a security hearing. The night before Edward Teller’s killer testimony helped condemn Oppenheimer, Teller and Wheeler sat in a DC hotel room, Teller unhappily trying to figure out how to testify. “Edward,” Wheeler said, “tell the story as you see it.” Oppenheimer lost his clearances and much of his position on the national stage.

§

By the time all this was over, Oppie no longer cared about the deaths of massive stars. But Johnny was interested in it and what it implied about gravity, and he went back to what came to be called relativistic astrophysics.

In 1958, they both went to the same conference on cosmology in Brussels. Wheeler gave a talk arguing with Oppenheimer’s research from 20 years before. Wheeler said he couldn’t believe that a star of great mass would implode into anything denser than a neutron star. Oppenheimer politely asked from the audience whether the simplest scenario wouldn’t have the mass gravitationally condensing to the point of disappearing from the universe. Wheeler politely disagreed; he couldn’t believe it was physically plausible.

A year or so later, computer simulations based on the codes used to simulate fusion bombs showed that a massive star living on thermonuclear fusion would die by imploding into invisibility. Wheeler was convinced and — as Oppenheimer had a few years before about the fusion bomb — changed his mind. But Oppenheimer didn’t seem to care, certainly wasn’t pleased.

In 1963, Wheeler and Oppenheimer were at another conference together. Wheeler gave a talk full of enthusiasm about imploding stars and conceding the correctness of Oppenheimer’s early idea that they’d disappear. While Wheeler was talking, Oppenheimer was sitting outside the hall on a bench, Thorne wrote, “chatting with friends about other things.”

In 1967, Wheeler was giving yet another talk and said offhand that after you say “gravitationally completely collapsed objects” enough times, you start looking for another name. Somebody from the audience yelled, “How about black hole?” Wheeler said he’d been looking for the right name for months – in his car, in his bed, in the bathtub – and suddenly this name seemed exactly right. He decided to use “black hole” casually “as if it were an old familiar friend,” and wondered, “Would it catch on? Indeed it did.” Every schoolchild uses it, he wrote. ****

Dyson thought that Oppenheimer’s early work was among “really the most substantial contributions to physics that he had ever made.” Oppenheimer “lived for twenty-seven years after the discovery, never spoke about it, and never came back to work on it,” Dyson said. “Several times, I asked him why he did not come back to it. He never answered my question, but always changed the conversation to some other subject.”

§

Oppie’s and Johnny’s war doesn’t sound titanic. Their arguments were the usual scientific disagreements and ended in not-unusual ways, with mathematics and/or evidence forcing agreement. Their antipathy seemed personal. Dyson wrote that Oppenheimer never took Wheeler’s work seriously. Wheeler wrote that Oppenheimer was so complex, “I never felt that I really understood him. I always felt that I had to have my guard up.” (Dyson didn’t much like Oppenheimer either, said he was disappointing.) Thorne quotes a physicist and close friend of Oppenheimer’s saying that Oppenheimer was widely interested in religions and felt uncomfortable at the outer borders of physics. Anyone meeting Wheeler knew that the outer borders of physics, or just outside them, was where he lived.

So what to make of their long war? Maybe just what humans have always made of the wars of the gods: awe, some confusion, and good for a gossip.

*I count astrophysicists.

**I paraphrase without necessarily assigning the tweets to the right physicists.

***Kip Thorne was Wheeler’s student; later they co-wrote, with Charles Misner, what is still the standard text on gravitation, called Gravitation. In 2017, Thorne won a Nobel Prize for his work on gravity.

**** I deleted a sentence about Oppenheimer never using the phrase, “black hole,” because it turned out to not be true. See the original comments.

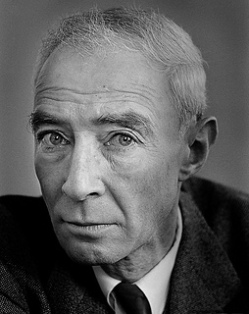

Photo credits: John Archibald Wheeler – used with the kind permission of Dr. Roy Bishop, via the AIP Emilio Segre Visual Archives; J. Robert Oppenheimer – by Alfred Eistenstaedt, via Flickr user, James Vaughan

Brava! Fascinating and deftly done! Who doesn’t love a tale of two egos?

I do thank you, Adrian! And your interview with David Cassidy in Science is excellent for any reader who might want, you know, actual authority and context: https://www.science.org/content/article/movie-adds-oppenheimer-s-celebrity-just-how-good-physicist-was-he

I have a good friend who sometimes tells his wife, also a good friend, that she is like a black hole. In the academic building where we both hang out & sometimes do work, the wife and I often return to this idea of her being like a black hole. We never really try to explain it or get to the bottom of why he thinks of her this way. Sometimes her being like a black hole is a sort of painful joke that we mention in order to make the idea lighter. Sometimes we approach the idea of her being like a black hole with a sort of reverence. Ah yes, we think, this explains something. But what? Then we pause, knowing all the time that the way her husband thinks of her probably says more about him than her.

So, I think of black holes and I think of love and our inherent (very human) mysteries and friendship. Thanks, Ann Finkbeiner, for complicating my notion of friendship and black holes!

I revere those (and today) scientists as muchas the public loves the big stars of sports, they are my Shohei, James, Messi, and does not diminises my appreciation for them that in the relations with people, or between themselves, they were (and are) just like normal people, because they are just human beings. Thanks for the delightful reading.

I wonder if being called a “black hole” implies some irresistible attraction? I also wonder if Oppenheimer

intuited (perhaps erroneously) some weapon beyond the fusion bomb (say, a gravity bomb?) causing him

to cease in pursuing that direction. Thanks for the read.