Ann: Nine, or who’s counting, ten years ago the consummate professional and pot-stirrer, Dan Vergano, and I posted a conversation about the science writer’s sad place in the media. Dan called this place the science ghetto, though I’m pretty sure we can come up with a better term — a bubble? A walled garden? The post’s commenters, who included what seemed like half the science writing community, argued about whether science journalism is or is not, and should or should not be, in its own small, walled hilltop town.

But in the last nine years, we’ve been through a lot, yes we have. And maybe the big problem isn’t that science writers are not proportionately represented on front pages. That is, something is very different now.

So we’re talking about it again. Dan and I are joined by two other consummate professionals and (with modest pride) ex-People of LWON: Virginia Hughes and Thomas Hayden.

The original conversation ten years ago centered on Tom’s idea that when science writers write about “mummies, exploding stars and the sex life of ducks” – in Dan’s translation – instead of about the science of “whether Iran really will have the bomb, whether quantitative easing will spark inflation” they make themselves irrelevant. And as a correlate, at the high desks of the influential media no science writers sit.

The commenters defended mummies and duck sex with the same reasoning that scientists defend science driven by curiosity: The world is lovely and odd and large, aren’t you interested? And anyway, the sciences of climate and ecology and medicine and genetics do directly affect people.

So, Dan, given that a LOT has happened since this argument, do you think science writers are still making themselves irrelevant, are they still in their private garden? Has that changed?

Dan: Oh yeah. I think people have been driven out of the garden. The twin shocks of Trump’s election and the pandemic forced a lot of folks to give relevancy a stab. Not to take a victory lap — because it was driven by a terrible human calamity — but some of the very commenters on the original post who knocked the science bubble idea ended up way out in front on pandemic reporting. (One of them won a Pulitzer for it, not to again pick on duck sex and poor Ed Yong, who is really the kindest guy in the world.)

Ann: I want to interrupt to say that Ed — whose series on Covid is a shining example of what humanly relevant science writing can be — explained that he’d been happily learning how rattlesnakes and mantis shrimp saw life when Covid hit, and he didn’t even know what science writing was any more.

Dan: And there are a lot more science writers, as a proportion of the field, now tackling not just climate change and public health, but also scientific misconduct and the ways science agencies spend their money.

Beyond that, I would argue that even the folks who just want to write about exoplanets or fireflies can’t escape relevancy in our era. The question of regulating, say, water-polluters or carbon-emitters has politicized our world to the extent that choosing to write (accurately) about science means choosing sides.

The real question for me is, did it matter? A critique I didn’t hear was that everyone tunneling out of the science bubble and getting their hands dirty writing about the science of how the world was run wouldn’t make a damn bit of difference. But that might have been a fair point. A million dead Americans later and the anti-vaccine movement snug in the bosom of a major political party, I have to ask myself if my bland assurance that it would matter was silly and naive.

Ginny: Can I sneak in here with a counterpoint, though? I agree with you, Dan: Science writers have become a lot more attuned to policy and politics. And major publications’ homepages/ A1s certainly feature a lot more science — Covid, Havana Syndrome, Russian nuclear policy, climate change, fetal tissue research, UFOs for Christ’s sake!!!, on and on.

But I’d argue that the past six years have also brought a renewed hunger for the irrelevant science, the awesome wonders of the universe that allow us to take our minds off of relentless misery and political divisions.

Ann: Oh man, Ginny is so right. I’ve started working on the least socially relevant subject on earth, the structure of the Milky Way, and I can feel my faith in life growing every minute.

Tom: Reading these comments reminds me why I so enjoyed being part of LWON, and of science journalism – there aren’t many other groups I’ve belonged to where smart + thoughtful + nice are present and valued equally. I’m particularly struck by Dan’s distillation of where we are now: “choosing to write (accurately) about science is choosing sides.”

Of course, as any of us who wrote about evolution or climate change back in the before times knows, that has always been the case, at least for some topics. But it was easier back then to chuckle over being roasted by the anti-evolutionists when they seemed like a harmless fringe, or to tell my environmental communication students to forget about the climate-change deniers and focus on the movable middle. Now the deniers — of climate change, of vaccination, of the value of education and science and maybe of rational thought itself — have moved from the fringes into the centers of political and cultural power. So, writing accurately about science at all is now a political act: so be it.

Ann: (trying to keep track of the logic here) Ok, so universal wonders are still worth the effort. And science writers have increasingly accepted the mission of social relevance. But these days, writing about science at all, let alone socially relevant science, means taking political sides. So where has that taken us? so then what?

Tom: Then I lean back in the La-Z-Boy recliner and, mixing metaphors from the sidelines, adjust my lenses and zoom out, and – oh shit. Science writing might be less segregated within journalism, but journalism broadly (the kind with facts and verification and stuff) is way more marginalized within the broader communication ecosystem. Like, way way way more. It leaves us in the unpleasantly ironic situation of having more, better, and more widely accessible science journalism than ever before — and having it all but swamped out in the cesspools of rumor, innuendo, rushed nonsense, crass marketing, devious disinformation and just endless quantities of mediocrity in which it is forced to swim and fight for attention. As Dan said in an earlier email, “the channels for injecting imbecility into people’s hind brains [are] so overwhelming” that looking to any reforms within journalism for help is just kind of pathetically out of scale with the scope of the problem. It’s sad even to look for salvation there.” He’s … not wrong.

Ann: So the whole ecosystem of journalists/information/readers has collapsed, and where does that leave science writers?

Tom: Science writing is no longer walled off from the halls of power so much as it is exiled to a lovely-if-impoverished island of rigor and craft, rationality and wonder within the fetid swamps of the broader culture. For better or worse, we no longer inhabit science bubbles; we cling to life within science refugia. And perhaps, like deep-rooted grasses and elegant butterflies and scrabbling little mammals holding on through the last Ice Age in a sheltered valley somewhere, we will be able to spread out and flourish once again once prevailing conditions improve. How they improve, whether they improve, I fear may be beyond our puny ability to perceive, let alone put into action.

Ann: Tom, I love and admire you, but that’s sheer poetry and about as useful.

Ginny: Could we maybe avoid referring to readers’ imbecility-infused hind brains? Or the “fetid swamps” of American culture? Do you know these people? Come on, Tom! You sound like a Californian talking about snow. (Which I know is a sick burn on your Saskatchewanian heart.) Many people I love would probably fall into the categories you’re referring to, so I’m perhaps a bit defensive. But seriously, isn’t one part of our problem the tendency to write off broad swaths of the country as bad/dumb/hopeless/deniers/brainwashed? My worry is that holding that posture will further erode trust from those groups, and ultimately shrink your “refugia.”

Dan: I do think there is value to what Tom is saying (if I am reading his poetry right) in keeping alive the idea that a critical, honest, and fair look at reality is our fundamental responsibility. We are not entertainers, swindlers, or commissars, and by keeping alive the sheer, weird idea of presenting news honestly to the public, we are preserving some of the Enlightenment for our children, whether we are writing about supernovae (supernovas? Ann would know) or about the latest mask guidance.

Ann: Supernovae. Or whatever some copy editor says. Dan, are you saying that readers increasingly understand that science might be the best way of thinking through a problem but even the best way has dead ends and branches? And so sometimes science, for a while anyway, might be getting it wrong?

Dan: I think that the idea of science as always moving, a rough, restless beast rather than a snoring oracle (the last word on nothing, to borrow a phrase), has permeated science writing in the last decade. I am a judge on all sorts of science writing contests (a kind of “always a bridesmaid” consolation for a long career), and the scientist-at-work piece — here she is drilling into a glacier, or paragliding over a whale — has become a staple. As well, a whole generation of news editors have had a rough apprenticeship in our world of pre-prints, peer review, and sordid squabbling among scientists, enough to get the idea that we really don’t know much about a lot of things, and a lot of what we think we know is probably wrong or incomplete, or we botched the experiment somehow. So I think we are farther along on presenting ‘science as a process.’

Ann: So ok then, maybe one difference between a decade ago and now is that readers likely understand that scientific knowledge is contingent. That’s good, right, I’m taking that as good.

Dan: Where we have failed, I think, is to take the next step, to get across to people the truly radical idea of science, to trust nothing that isn’t verified by repeatable experiment, and to distrust even that. Are we willing to tell the public what this really means?

Before Ann can ask, here is one way of what I mean: On January 17, 2020, the CDC should have hammered home in its first briefing on the novel coronavirus that we didn’t have a goddamned clue how this new bug worked. And that their best advice could and would change radically as we learned new things about the bug. I asked the penultimate question at this briefing, asking Dr. Messonnier to lay out why a novel coronavirus was such a concern. I don’t think I did a great job of grokking the horror of her answer. And to be honest, she sounded matter of fact as she said it. But going back and listening again (~minute 25) now, she sounds quite worried. I think I reeled from understanding its import.

Ann: I remember her briefing a month later — ““Disruptions to everyday life may be severe” — and I remember thinking, “it can’t be possibly that bad, can it?”

Dan: Science reporters should have shouted this at every step of the pandemic, that the situation was horrible but right now it’s the best scientists could do. Underlying all this was a primordial fear of panicking people (imho) by telling them that until we let science make its fumbling, bumbling way, one repeatable observation at a time, we didn’t know how the virus was going to go. We shrink from telling people there aren’t answers.

Ann: I do believe that people aren’t dumb, that they can understand contingent knowledge, knowledge for-now. And that’s one thing science writers can do: say this explicitly, not make it sexier or scarier or simpler than it really is. What else can we do? Do we keep fighting misinformation and disinformation? Should we make a nice bulleted list of What Science Writers Can Do To Secure Rationality?

Ginny: I think we should spend less time refuting disinformation/misinformation/whatever the hell we’re calling stuff that is wrong/misleading, and instead focus on reporting new stories. I’m not convinced that debunks change many – or any – minds. But when you break news, people of all stripes pay attention.

Tom: Ginny is verifiably right about the higher value in reporting real stuff than in refuting nonsense–all the science of science communication research supports that. And yet, she did a brilliant job of refuting my nonsense way back up in the middle of this post. It’s true! I am nothing but an armchair observer, not having committed an actual act of journalism, science-writing or otherwise, in a decade or more. Maybe I am just pearl clutching about snow reports from a distance (the salve of Ann elevating my drivel to the status of useless poetry helps ease the sting from Ginny’s very sick burn) but to be clear, I am doing so with admiration and respect. I see tremendous value in continuing to do the work of science journalism no matter what metaphor applies–just as I see value in conservationists shooting invasive opossums to save the last of the flightless parrots in New Zealand, or medieval monks laboriously copying manuscripts on some rock off the coast of Ireland. Or, you know, dedicated professionals providing one of the necessary conditions for a functioning democracy. I love the people who do it, the people who consume it, and the people who critique it with seriousness and care. But I love most of the people who don’t, too! Whatever scorn dripped from my keyboard above was meant for the injectors, not the injectees; for the swamp fillers, not those filled upon. But Ginny’s critique is still right: this work works best when done with respect and love for the audience and broader society. Ultimately, “journalism” is a verb, as I tell my students (sure, the grammar is wrong but the deeper meaning is true), and armchair pearl clutching from the sidelines adds nothing.

Ginny: To fess up a little, I have certainly assigned reporters many debunks over the years (just ask Dan, who followed my orders beautifully)… I just have the queasy feeling today that those efforts may have been for naught. And I wonder, in retrospect, if the opposite approach would have been more fruitful. If we could go back in time, and for every forceful debunk, instead engage with the skeptics/deniers/earnestly curious folks head-on, starting from a place of empathy… But then I’d most certainly be accused of “bothsidesing,” which has somehow become the Gravest Possible Sin for our profession. The point is, I don’t have any bullet points for your list, Ann!

Dan: Unlike Ginny, who possesses a kind of steely self-possession and moral fiber whose gross lack has kept me safely out of the editor’s chair for many decades, I am helpless in the face of an editor asking for bullets, and must comply. To summarize:

- Everyone has to deal with reality in their science writing now, at least sometimes, because it has bulldozed holes in the walls of the science ghetto.

- The most effective and radical act in the Age of Grift & Politics is to report the news in a critical, honest, and fair way.

- That means we have to be honest with readers when science lacks answers. (This also means we have to be honest when there are answers; the climate is warming, vaccines save lives, fentanyl doesn’t cause overdoses on skin contact.)

- Rather than first reach for the debunker, consider exploring behind the bunk to see why people so easily embrace a delusion.

- Supernovae. Or whatever the copy chief dictates.

Ann: I note that when I ask three science writers to summarize with bullet points, one complies brilliantly, one writes an apologia pro vita sua, and the third one flatly refuses. I begin to sympathize with editors. Anyway. I’ll add one bullet point.

- Extend our remit to social media, and Like and Love and RT and QT and generally support and promote all posts that tell whatever truth exists about Covid or the Havana Syndrome or extraterrestrial aliens. Flood the zone, dazzle ‘em with sweet reason.

____________

Thomas Hayden has been on staff at two news magazines, has free-lanced everywhere, and currently runs the Environmental Communication program at Stanford University.

Virginia Hughes was deputy editor-in-chief at BuzzFeed News and is currently a science editor the New York Times.

Dan Vergano was a science writer/reporter at USA Today, National Geographic, and BuzzFeed News, and is currently a science reporter for Grid News.

___________

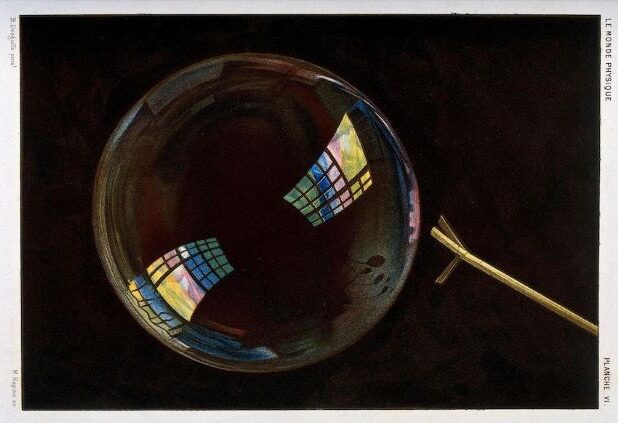

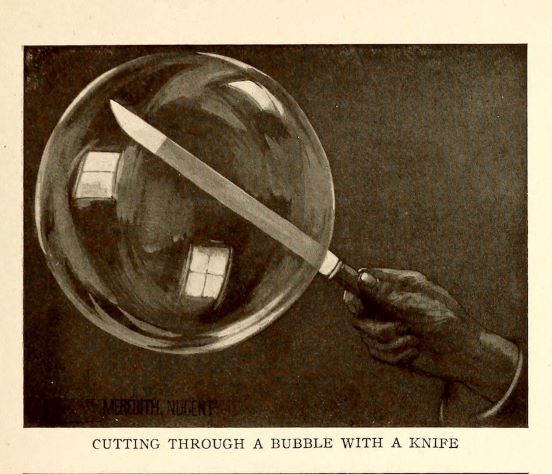

Illustrations from the always-splendid Public Domain Review

Could I really be the first to comment on this moveable feast of a conversation about science journalism? I haven’t been writing many stories right now while working on getting the Big D (divorce, I’ll spell it out, because some people call a degree a Big D, too).

But I want to add a tableau to your round table. I’m teaching a first-year composition class at this technical college in my town. I themed the course “How to Find Your Way.” So, yesterday, I collected papers in Wayfinding, and then proceeded to present the next assignment as I do by showing them how I’d go about writing my own next paper.

Students are going to write Definition and Description essays about something in their field of study (think screwdrivers, embalming tools, plumber’s dope, game design programs). I presented my field as science writing. I showed up with a stack of heavily notated articles about Thwaites glacier, 10 lbs. of science textbooks I bought for 3 dollars each, a science calculator, a sound recorder. I told them about MIT and Yale and other really good schools making recorded lectures of real science classes available to eager folks like me. I wore Carhart overalls, good for following a wildlife biologist around. I showed them wind maps and Nadieh Bremer’s “Planet: Imaging the entire Earth, every day.” I told them what “object” I’d choose to define and describe in my own imaginary paper.

The 18-year-olds looked at me as I declared my devotion to science writing. They watched me walk back and forth, and pick things up, and point at the screen where the wind maps were moving their wind around.

I will write more science stories one day, possible sooner than I think. Major life changes sometimes interfere with the mind’s ability to get truly lost in the subject matter. Or I can get lost in geophysics, in satellites, in the minute structure of mosses, but right now…I just don’t have the focus, or the attention, to write the story that helps me find my way out. I don’t have the power to finish writing science stories even if I can get started–but I will again soon, I promise myself.

In fact, I think I left my spouse in order to write science stories. So that is what I’ll do!