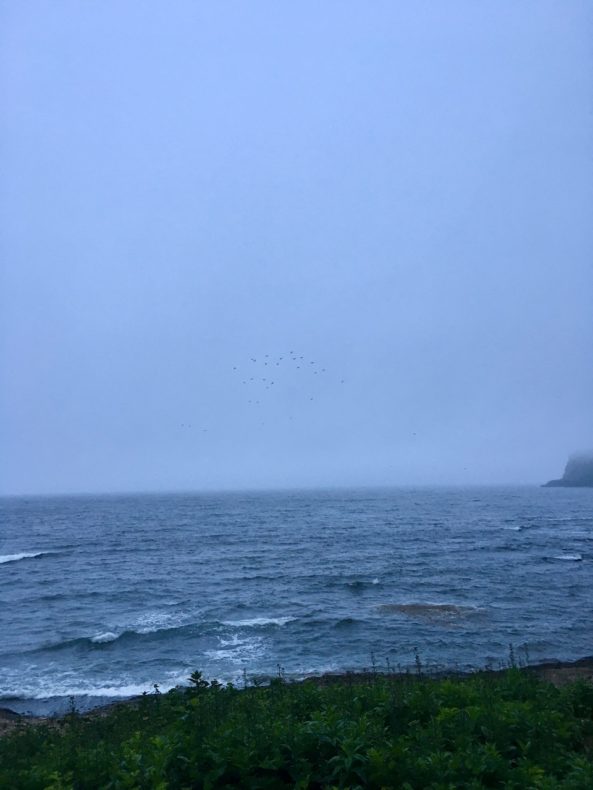

The fog is thick and so you hope the auklets will come early. They do, a few minutes before sunset: ten, maybe twenty of them, although it is hard to tell since they are for the time being far enough away to be little more than dots. They circle over the waves in a tight group, not daring to stray too far from one another as they follow some vague clockwise circuit. Then they vanish back into the fog.

They reappear a few moments later, more of them now: thirty, forty, plus or minus. They swing closer to the land this time, being less leery of it, perhaps, and you can make out the details of their bodies, their heads, their feet splayed to steer, and of course their wings working madly. Then they twist away and become dots before again moving out of sight.

When they come back this time they are more than one hundred. In the distance you see that another group has formed behind them. Before long the groups have merged to become a ceaseless stream of birds in their band of sky.

More auklets join, and more and more. Maybe something has signaled to them that it is time for this ritual to begin in earnest, maybe the light dropped below a certain acceptable threshold and they feel safe from the eagles and falcons that try to eat them. Their joining is subtle at first, but then you realize that they fill the whole sky, all its layers up as far as you can see. You stop trying to guess how many auklets there might be, having to be satisfied with thousands. A few—those with chicks to feed—have fish dangling from their bills. They whirl once or twice with the madding crowds before peeling off and heading for the island, whipping in on stiff, crooked wings, and you hear the delicate crunch as they smack into the bushes. But most keep flying and flying.

Sometimes you can hear the whip of wingbeats over the steady pulse of the surf, but only when the auklets are near to you, flying right over your head. Some are so close they seem inches away, and if you were so inclined you could reach up and grab them out of the air. But you don’t. Instead you try to track this one or that one for a few seconds, until the effort of focusing on a single animal among so many is too much and in relief you go back to looking directly overhead at a blur of flight. Eventually you are so dazzled and tired from watching all the auklets that you lie down on your back on the wooden deck and let birds wash over you like water. You know that most of the ones without fish or anything else to do are likely failed breeders, or young birds that did not try to breed at all, and so for the purposes of accounting are not as valuable or worth paying attention to. Yet they keep flying, for clearly they think their lives are still worth living, and there is always next year, or now, and anyway the lines you have drawn around periods of time so you can say “breeding season” or “non-breeding season” mean nothing to them. You wonder what the purpose of this exercise might be, what the auklets are expressing or telling each other in this moment as they race overhead without uttering a sound, but maybe it is not for you to know.

Thanks, Eric, for reminding me what we see when we sit still for long enough in this world. Sometimes I think to have a sublime moment like yours, I must return to school and study biology or conservation, and take internships where I’m stringing up nets in the night to catch bats. And only on my third or my tenth summer in the field would I see anything like what you saw.

But I think there are people with these kinds of degrees who still see nothing. Just like there were people in my graduate program in creative writing who never read books. There’s all kind of training for how to be observant in this world, I suppose, and maybe one kind of training works as well as another if I just get outside often, and make a study of what I see.

This has been my summer of the frog pond. I go with my two little boys before bed, and I go without them when they’re with my husband. I’m learning to spot frogs in the pond and toads on the trail, and to tell the difference. I go to listen to their sounds, and to see the swaying of reeds in the water. I’m never disappointed, even if sometimes think this will be the night when I see nothing and I only go home with mosquito bites. For now I appreciate the solitary nature of these frogs when they’re hunting, and how easy they are to miss, except for that one sharp movement, and then a splash.

Thanks much for your kind words and thoughts, Rachel. I’m always happy to remind people to sit still and watch and do nothing outside, whether at a seabird colony or a frog pond. And as a further plug for the practice I think it’s neat how sitting still / watching / doing nothing can bring the same fulfillment via both big and obvious things (like a gathering flock of auklets) and secret, furtive things (like frogs).