After five years of breathless headlines about the deepfake threat, it finally happened. Earlier this month, a video purporting to show Volodymyr Zelensky surrendering to Russia was broadcast on a news station in Ukraine, from which it swiftly jumped to social media. Well, it kind of happened. An army of researchers was at the ready, and immediately found the original (real) video that had been used to generate the fake. They debunked it, but also issued a stark warning: the technology is only going to get more convincing and harder to spot.

That line has been in every single article about deepfakes since 2017, when a redditor struck nominative gold by sticking the word “deep” (which was associated with AI) in front of the word “fake”. It sooon became the name for the general practice of using software (AI or otherwise) to create a digital doppelganger of anyone or anything you could possibly desire, and make them do or say anything you want. The face swapping technique that put Zelensky’s face on another actor to puppet him is probably descended from the original used by “deepfake” to swap famous actresses’ heads onto bodies in porn videos. These early videos were only convincing to the people who really wanted to be convinced, but any day now, the story went, such AI-generated images and videos and voices would become so utterly convincing that they would bring the world down around our ears. There would be fake gotcha videos of politicians saying something they never said; public nonconsensual pornography to silence and humiliate marginalised people; fake voices and faces to aid high-tech robberies and phishing scams. It was inevitable.

Three years later, I was working on an article about the evolution of the AI under the technique’s hood. By then, the election loomed (you know the one). Everything was a whirlwind of congressional panels, multimillion-dollar technology accelerators launched to detect and defend against the threat, and impassioned senators railing photogenically against the coming technological calamity.

All the worst predictions seemed to be coming true. A deepfake app had just been released that could create a naked picture of any random woman on the street with the touch of a button. A journalist critical of a repressive government had been humiliated and sent into hiding with the release of a pornographic deepfake. A Gabonese politician was thought to be dead, and what was meant to be a reassuring video of him being alive and happy seemed deeply suspicious. It was happening.

But my article wasn’t going well. It was proving a nightmare to write (I still wince when I think of the plight of my poor editor) largely I think because the copy was showing the deep seams between what I had assumed in the pitch – deepfakes will become an epistemic nuke – and a different reality that had become increasingly clear to me in the course of the reporting. The rogue app’s creator took down the app. Ali Bongo was actually alive. All the little deepfake skirmishes seemed to fizzle.

With my bad draft in limbo, I wrote a separate little interstitial piece for a different magazine, in which I wondered why. The answer from experts was that the tech was still too complicated for deployment by the average ne’er-do-well. It hadn’t been properly democratised yet, but when it is, they muttered darkly, just you wait.

Researchers publicised various “tells” that would help us spot a deepfake, while other researchers admonished us that the technology was improving so fast, these tells would soon be gone. They were right that the technology was improving at a staggering pace. But not the tech being deployed by the average ne’er-do-well. The people with the money to pay for the expertise and processing power required to really drive the technology into the uncanny weren’t political trolls or sleazy dweebs with a one-off date rape app. They were car companies. Or Olympic teams. Or major league baseball teams. Those were the kinds of interests for whom deepfakes held the most promise.

I talked to car manufacturers who were able to test aspects of car design entirely in simulation for the first time. I heard about major league baseball teams and Olympic teams using special deepfake cameras to individually segment every kinematic change in a movement to help athletes analyse failure modes. These were the kinds of projects that were pushing the technology to its full potential. The companies hiring the top flight researchers weren’t distracted from their use cases by the senate subcommittees and all the gavel pounding. It was like they existed in a separate universe where the research-grade deep fake tech was accelerating madly and to amazing effects, but this acceleration gave no ammunition to bad actors’ ability to use the technology to burn the world.

In fact, sometimes it seemed like there wasn’t a lot of air between the research projects that were purporting to warn of deepfakes’ unique dangers and the ones that were advancing the technology of deepfakes. That’s hardly an indictment. The same dynamic happens in other scientific arenas like gene-editing. What made this particular instance a little bit harder to swallow, though, was how hard Facebook leaned into it. They launched a gigantic program with all the top researchers in the field to defend democracy from the evils it was about to withstand. That seemed right, given that it was 20202 and who knew what fresh hell waited around the next corner. But you may recall Facebook was having some other much publicized issues at the time, so a big reputation-laundering Manhattan Project against the Deepfake Apocalypse was a much needed PR balm.

My very bad article got killed (by mutual, conscious uncoupling). I went off to hide in shame under a duvet and waited for the deepfake asteroid.

When the Zelensky face swap dropped, experts immediately pointed out that it was unconvincing. It melted under the scrutiny of the infrastructure of professional deepfake fact checkers ready with their magnifying glasses.

So maybe all those alarm bells did their job! Maybe the reason the Zelenasky swap proved unconvincing was because years of breathless doom-mongering had so successfully prepared us to spot deepfakes.

Maybe. There are holes in that story too. First, a lot of the harm done with “deepfakes” to individuals and democracy can be done better – and has been – with other tools. Second, other studies have begun to suggest that most people are no more swayed by deepfakes than they are by other media fakery, including text articles. Third, and most important, it’s possible that all that deepfake spotting has had some other deleterious effects in the meantime.

A study published last month in the Journal of Online Trust and Safety suggests that shouting at people about the danger of deepfakes might do more harm than good: John Ternovski, an analyst at Georgetown University, and P.M. Aronow, a political scientist at Yale, ran an experiment in which they warned people about the existence of deepfakes. Then they showed them a political video. After they were informed of the existence of deepfakes, people simply gave up. Instead of trying to squint harder or whatever you’re meant to do to spot a deepfake these days, they simply threw up their hands and decided that any videos they were seeing were fake.

So did all that deepfake apocalypse talk preemptively disarm videos like the Zelensky one, making them much less likely to stick their landing? And is that a good enough reason to poison the epistemic well? Should we be worried that people are so enthusiastically throwing good information after bad?

Because honestly, what even is the point of a separate category called “deepfake” in the age of QAnon, where all you need to spin up an alternate reality is like, a Wordle? When the ubiquity of Instagram filters make women run to the plastic surgeon to replicate the way they look in a selfie on a web site? When mid-table celebrities are trying to get you to buy ugly blockchain “art” that’s really just the equivalent of going to the store, buying a bunch of stuff, and then setting fire to everything but the receipt*. Deepfakes arrived late to a crowded party. Deepfakes are dead.

This is the part of the article where I am contractually obligated to add: Deepfakes are dead, for now. Eventually they will get so good we won’t know how to spot them, and then just you wait. Long live deepfakes.

*I got this metaphor from Ryan Broderick’s excellent newsletter Garbage Day, but can’t find the exact one to link to it. But you should read Garbage Day.

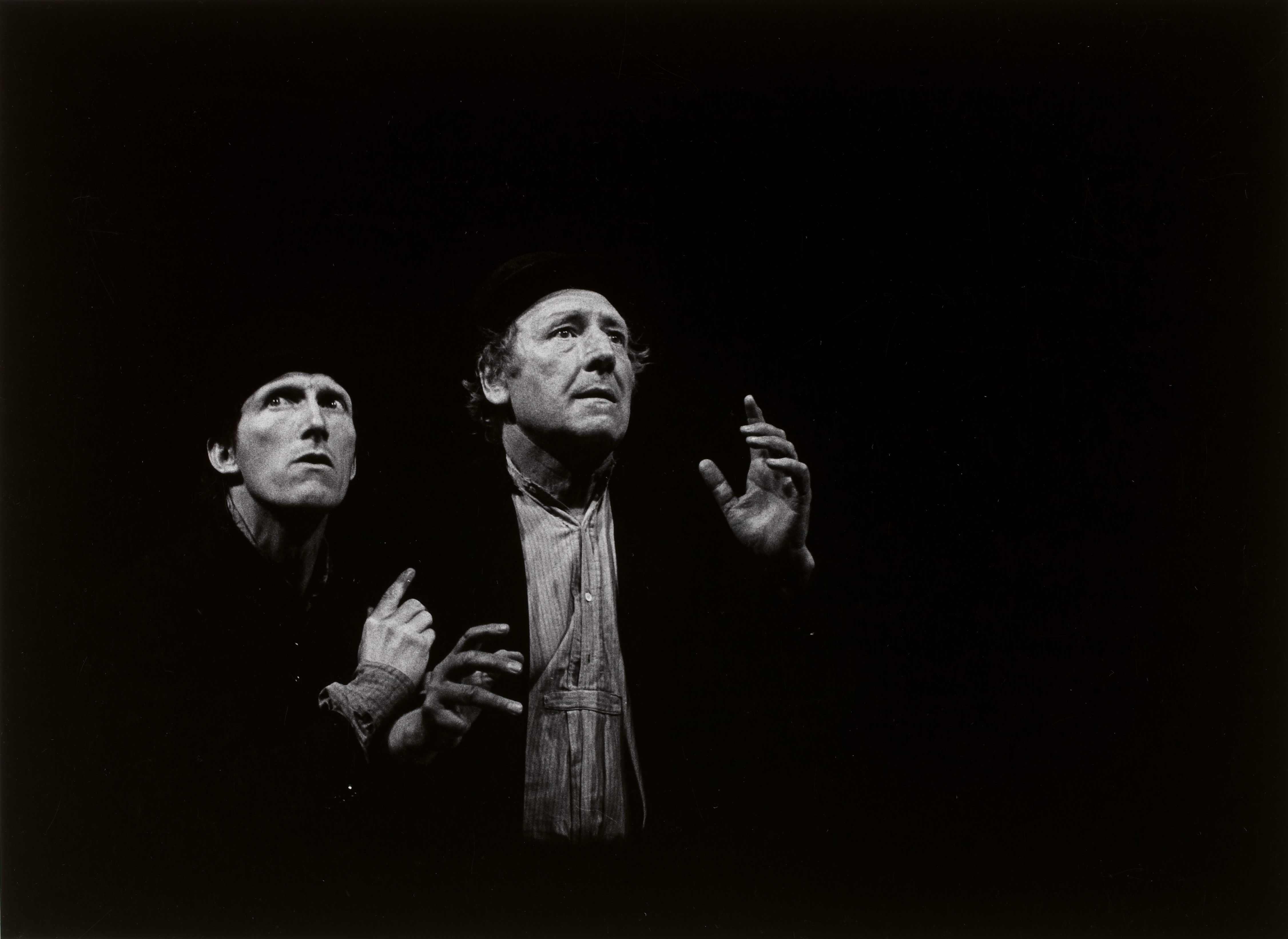

Image credit: 1978 production of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot. Photographer: Fernand Michaud, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons.

We had someone post a faked picture of an alligator in the Sacramento River. It was proven false but that didn’t matter to those who wanted to believe. “It could happen” “stranger things” and other such comments were their reasons.

Thanks Fred – as Nessie chasers attest, “I want to believe” is more powerful than any fact. Only matched by “I don’t want to believe”, which can be exploited by bad actors in what’s known as the “liar’s dividend”. Searching that term will send you down all kinds of fun rabbit holes if you’re interested. Thanks for reading.