The first woman to get a Ph.D. in oceanography in the United States—and in North America, and, perhaps, in the world—was Easter Ellen Cupp. She received it from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in 1934. I learned this because I have been reading about one of Cupp’s supervisors, a man named Harald Sverdrup, for a book on seabirds I’m supposed to have finished. When you work on a book about a science, you tend to read a lot about some very hardworking and accomplished people. Their stories can leave you (me) feeling kind of lousy about your (my) work ethic.

Such is the case with Harald Sverdrup. He was really something. Born in 1888, in the town of Sogndal, Norway, he came from a family known more for farming, politics, and the Lutheran clergy, but he was drawn to the natural sciences. He went to the University of Oslo, where he excelled in geophysics, meteorology, oceanography. When he graduated he studied under Vilhelm Bjerknes, then the world’s preeminent meteorological theoretician. After he finished his Ph.D. he joined Roald Amundsen, who, a few years removed from his triumph at the South Pole, was planning an expedition to the North Pole. Amundsen never reached the pole, but Sverdrup collected reams of data on all manner of natural phenomena. When he returned from the expedition several years later he assumed Bjerknes’ old professorship at the University of Oslo, before being asked to become the director of Scripps in 1936.

At Scripps, Sverdrup more or less developed oceanography as a modern scientific discipline. He established a core curriculum and published the field’s first textbook, The Oceans, in 1942. The Oceans became the standard text for the next several decades; oceanographers still refer to it as “The Bible.” All the while Sverdrup was doing groundbreaking (or waterbreaking) research on the dynamics of ocean circulation, revamping also the research ethos to emphasize long pelagic cruises. He would eventually be memorialized as a unit of flow: the Sverdrup (Sv), or the volume transport of one million cubic meters of seawater per second.

Reading about Sverdrup’s life, especially in condensed form, it is hard not to indulge in a bit of hagiography. I see him, Saint Harald of the Moving Waters, besuited and trim, inspiring legions of young oceanographers as they sail off into the great blue world, keen to discover what needed to be discovered. He was by all accounts an excellent teacher and mentor, and many of his students became famous oceanographers in their own right: Roger Revelle, who was one of the first scientists to raise the alarm about climate change; or Walter Munk, who, with Sverdrup, taught military planners about surf and swell forecasting—knowledge that would prove essential for the Normandy landings in World War II.

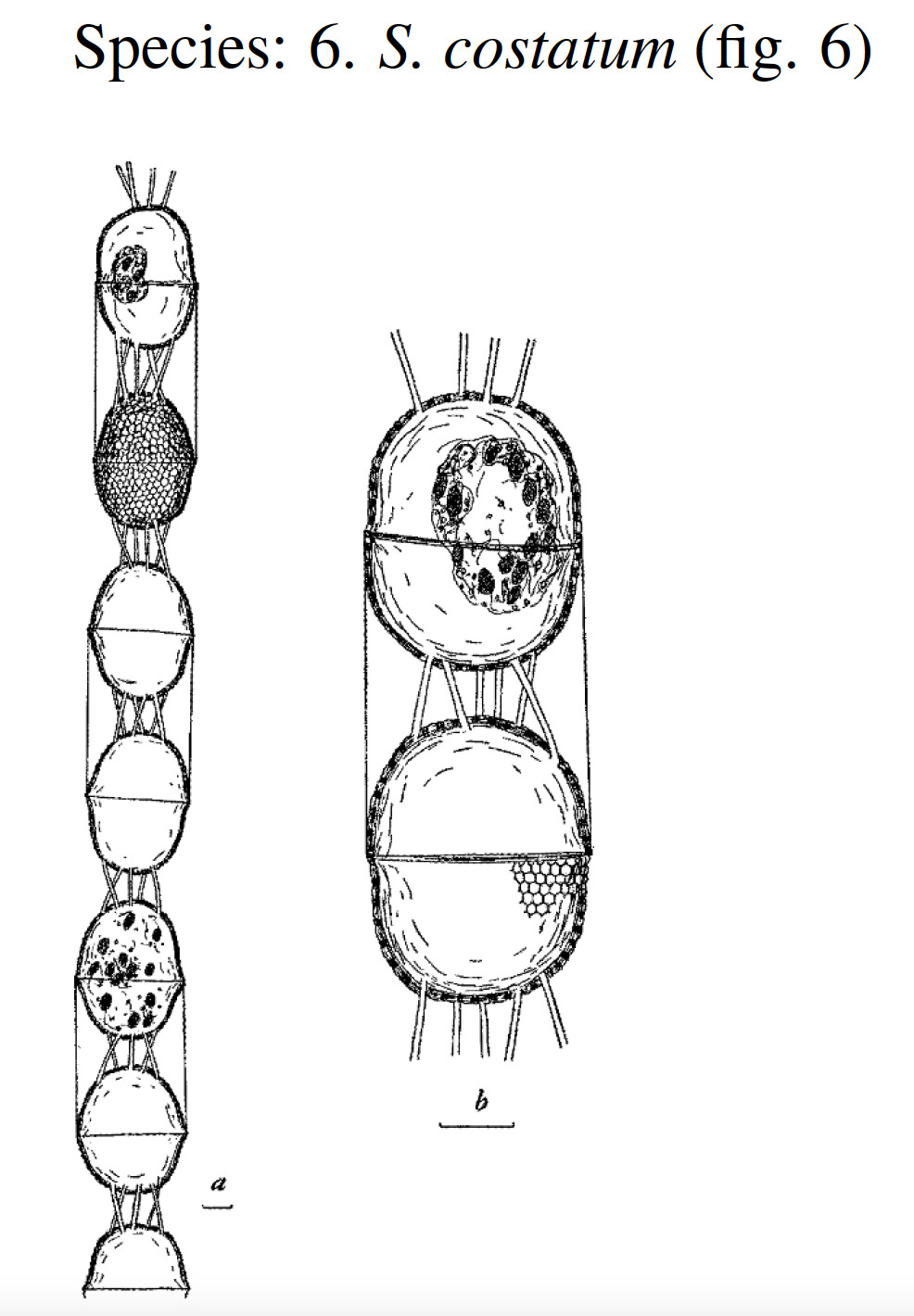

It was while following the spreading ripples of Sverdrup’s influence that I came across the bit about Cupp. The fact that she was the first woman to get a Ph.D. was given as one more feather to add to Sverdrup’s already well-feathered cap. Curious, I tried to find out more, and before I knew it I was into another of those recitations of professional accomplishment, leaving me with familiar feelings of personal inadequacy. Per the Special Collections of the UC–San Diego Library, Cupp was born in Iowa in 1904 and moved to California when she was six. She was an excellent student, and although her parents weren’t terrifically educated they supported her interest in science. She was the first member of her family to go to college, graduating from Whittier College in 1924. She went on to UC–Berkeley, earning an M.A. in zoology in 1928, and then to Scripps, where for her doctorate she studied diatoms, a type of phytoplankton. She published a book on them, which she both wrote and illustrated. It would be become a classic in the field.

Cupp’s story abruptly departed from the standard arc, like a bird shot out of the sky, when I found out that she left Scripps in 1940. Sverdrup had opted not to renew her contract. “This action is by no means intended to reflect on her ability or the manner in which she has conducted her work at the Institution, but has been dictated by consideration of the general scientific program of the Institution,” he wrote in a budget report. “Unfortunately the financial situation does not warrant the creating of a new position and much to my regret I found it necessary to discontinue the services here of Dr. Cupp in order to begin studies which at the present time appear to be of greater importance.”

From Scripps Cupp went to the Naval Biological Laboratory in San Diego, but she stayed there for only a couple of years. In 1943 she left oceanography altogether and got a job at Woodrow Wilson Junior High School, also in San Diego, where she taught English and basic science until she retired in 1967. She seems to have had no further association with Scripps until 1998, when she was approached to be interviewed as part of the Scripps Centennial Oral History Project.

The interview took place over two days and was conducted by Joellen Russell, a geochemist who has herself become a force at the University of Arizona, but when she spoke with Cupp she was a graduate student at Scripps. Their conversation is a little heartbreaking. Cupp was 94 years of age and “in ill health,” as well as hard of hearing. She was accompanied at the interview by her “lifelong friend” Dorothy Rosenbury; and they must have been very good friends indeed, because they had lived together for seventy years. Rosenberry does a fair amount of the talking, sometimes supplying answers, sometimes prompting Cupp, calling her by her nickname Easy, or Ease. When Cupp speaks, she tends to do so with single words or short sentences, or [not audible] or [no response].

Russell asks Cupp first about her upbringing, her time at Scripps. They talk about people she knew, and so on. Finally, near the end of the interview, Russell makes a gentle if somewhat awkward segue. “The last thing that I wanted to ask you about was how you left Scripps,” she says, “because there was a letter in your file from Dr. Sverdrup, and he basically tells you that they no longer have a place for you and that you need to find a new place to work, and I was wondering how that came about. Do you remember?” Before Cupp can answer, Rosenbury interjects.

Rosenbury: She was a woman! You’re a woman.

Cupp: Yeah.

Sverdrup had told Cupp he was letting her go because he wanted to move the research program away from taxonomy, and also because former students should not be encouraged to stay at Scripps indefinitely. But in the larger scheme, Cupp and Rosenbury were convinced, he chose not to renew her contract because he didn’t see a place for her—a woman—in his modern school of oceanography. This, while he secured funding for several of his male students. With his plans for long research cruises, the logistical exigencies he saw as necessary to make room for a woman on a ship were not worth the trouble; and so he soon hired a man who studied a similar topic to replace her.

The interview moves to some brief reminiscences from Cupp and Rosenbury about what it was like to teach at a junior high school, and then Russell brings things to a close.

Russell: This was really interesting. I’m very pleased. I think this was great. I’m really happy that we got through all of it and that you were able to tell me about how you left Scripps, because I wasn’t sure whether it was a good thing or a not-so-good thing. It sounds like in some ways it was difficult, and in other ways it was kind of a relief to have a permanent job.

Cupp: It was a more permanent thing.

Russell: Did you miss your research?

Cupp: Oh, I was always interested in that. I was glad to be on something [not audible].

Cupp would die a year later, at the age of 95. “Easter Cupp’s monograph on West Coast diatoms was, and still is, a major contribution to our understanding of the biology of the California Current,” John McGowan, a biologist at Scripps, wrote in her obituary. “It is accurate; it is precise, and was about 20 years ahead of its time. It will be in use for at least another 50 years.” Her book, of course, was not the only way in which Cupp was ahead of her time. Women at Scripps would have to wait until the 1960s to be allowed on research cruises as crew or scientists rather than uncredited helpmeets. Although some graduate students were still having trouble getting access in 1970 and beyond. But at this point I had to stop myself from straying so far beyond my brief, because even though it was a lot to sit with, none of it will go in my book. My book is supposed to be about seabirds, after all, and not sexism, or how much was and continues to be lost on account of it, or how disappointed I am in Sverdrup, or how someone can see so far in some ways and at the same time in others see nothing, or the tragedy of Cupp’s story, or the awful knowledge that there are so many more like hers, or the question of who is quietly paving the way for whom, or any of that. Right?

Photos from the University of California – San Diego Digital Collections

Great account. Thank you for this, Eric. A great story and a sad story. How sad that Cupp was left teaching high school instead of the research she was so good at.

I can easily understand how this is just another story of how women have been struggling to have a voice in science or math or engineering or or or… What I grasp like a life raft from this story is that she “taught” the next generation which is one of the greatest ways to influence young people that I know of. Perhaps she led or influenced many young people into field of the sciences.

Hi, Art and Tracie, thanks very much for your thoughts. Yes, it’s awful that Cupp was driven from academic science, but I agree, Tracie, that her teaching junior high school was not in itself a sad thing. It’s interesting to read her oral history, as she’s pretty matter-of-fact about leaving to teach, undoubtedly because, as you note, hers is “just another story,” and so she was living within the practices of her time, and why should she expect anything different? I don’t know. I guess in part it was her combination of extreme competence and resigned acceptance that I found most affecting–how, in her way, she pushed the light a little further against darkness, if I may paraphrase. And I’d like to think that she was an excellent teacher.