Not long ago, a friend who lives nearby, a skilled hunter of arrowheads, found a beautiful fluted spear point. It came from between his house and mine, along a ditch. The find was stunning, what I think has to be Clovis technology from 13,000 years ago, its point as sharp as the day it was made. I’ve held it in my hand, turning it over and over, one of the finer pieces of stonework I’ve seen. He found it, oddly, while picking up trash along a rural ditch. He figured it had to have been dredged up during modern history, dumped to the side, out of place, no known provenience, showing up here out of the blue. Maybe not entirely out of the blue, though, this point is part of a much bigger puzzle.

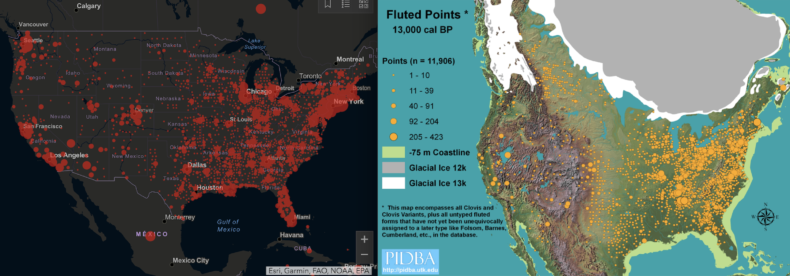

A week ago I snapped a shot of the coronavirus map for North America. This was before red dots merged and turned the US into a record breaking blot. Next to it, I placed a map of fluted projectile points from the Ice Age, dating to about 13,000 years ago. The two maps struck me as remarkably similar. What might be behind this?

Our modern gatherings and zones of interaction appear to have not changed much since the Ice Age. The same old passages are still open. Where people go, Clovis points and viruses follow.

In both cases, the East — which was heavy in mastodons back in the day — is the epicenter. The West, geographically and climatically more complex, prone to scattered communities, is lightly peppered with Ice Age artifacts till you get to the coast. If this map included stemmed points (as opposed to fluted), it would give us the coastal concentration we see on the viral map.

Some scholars have suggested the Ice Age map suffers from bias, saying that more artifacts tend to be found where more people currently live. But 90 percent of documented fluted points are from east of the Mississippi. That’s more than a bias. That side of the continent saw a cultural, technological outbreak in the late Pleistocene.

Florida seems to be one of the exceptions to these two maps. It goes blank in the Ice Age when this thumb of a state was one of the largest concentrations of dire wolves and sabertooth cats in the Americas. It was the North American savannah, and also the first place on this hemisphere where humans were proven to have co-existed with Pleistocene megafauna, discovered in 1915 on the Atlantic side where bones of 14,000-year-old people were found in the same layers as one-ton armadillos and bison twice the size of our own. People were likely all over this peninsula, but half of Ice Age Florida is now underwater and the rest has been a flux of shorelines and marshes. Fluted points showed up here early and stayed for thousands of years, suggesting Florida should be as bright with late Pleistocene activity as it is with registered cases of Covid-19.

We are still obedient to the lay of the land. Some places always see more human flare-ups. It’s not a new idea. Archaeologists thrive off the notion that we’ve been doing the same things in the same locations for most of human history. North America is a chess board, its pieces moved into familiar positions. Where do the big rivers flow? Where are coastlines protected, where do passes lead through mountain ranges?

Southern Arizona, thousands of years ago, was the site of a Neolithic-age irrigation society, an early Native American hydraulic empire of cotton and corn watered by more than a thousand miles of canals and ditches, which modern Phoenix built upon like a blueprint. Ten thousand years before that, it was a subtropical Ice Age paradise where numerous mammoth kills have been unearthed, revealing one of the larger Clovis occupations in the West, now a red-dot cluster of Covid-19.

People 13,000 years ago gathered on the Front Range of Colorado like a wave hitting the Rockies: Denver, Fort Collins, and Colorado Springs. Either side of the Appalachians looks like a bomb went off, which it did, culturally, the highest concentration of Clovis technology appearing in Tennessee and along the East Coast. The oldest known large gathering in North American history, the Bull Brook site from 11,000 years ago — a caribou processing and tool-making center that saw up to several hundred people — is in Ipswich, Massachusetts. The stones brought there for manufacture came from, on average, 300 miles away. People were moving, carrying themselves and their goods long distances, coming together in groups, a plan for how people have done it ever since.

Clovis tools and weaponry — bullet-shaped projectiles made of glass-like stone masterfully thinned — was one of the fastest moving technologies in the Ice Age. While the same old points were being used for 10,000 years or more, Clovis spread like wildfire, estimated to have broadcast across North America in 200 years. You might call it viral. In short order, the same unique point was being made in Delaware and California. It wasn’t long before fluted points reached Alaska and the tip of South America. It’s something our species does well: spread and remain connected.

During this pandemic, one solace I personally take is that my family and I live in the Intermountain West, where both maps are emptier. I’m hours from the nearest interstate, the closest town just over 500 people. I prefer living away from the action. The archaeological sites I know around here don’t have fluted points. An archaeologist worked for years on a cave not far from where I live in western Colorado, where he took occupation dates back to 13,000 years ago. Almost proudly he says he didn’t find diagnostic weaponry at the site, no Clovis technology. All they found were cooked rabbit bones and deer, people eating grass seeds and hammering rocks into tools. These were utilitarian folks living in the middle of nowhere, far from the Ice Age hustle and bustle.

There is no getting away from ourselves. The county next to mine has 39 Covid-19 cases as of now. My county is at 11. My friend found the Clovis point just a couple miles from my home. He picked up a tool from 13,000 years ago, a reminder that no matter how far we go, we are bound together. The finest threads connect us, make us the same.

Maps: Paleoindian Database of the Americas https://pidba.utk.edu/maps.htm and the coronavirus site from ArcGIS https://gisanddata.maps.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6

Photo: Projectile found near me by Kyle Devin Vaughan

Really appreciate your writing.

Craig- This essay was particularly meaningful for me and my interests. My wife’s family in eastern KY found several projectiles while farming near Blue Licks State Park where Israel Boone died in a cave after having been shot with a projectile. This also reminds me of our discussion about borders. Cheers, Salmo

No matter where we go, there we are. I am a bit puzzled by the reference to the “Pacific side” of the Florida peninsula. Did you mean to say “Gulf side”?

Wow, Curtis, thanks for catching that. Late at night while I’m writing, oceans change places.

Thanks for this Craig. Right to the Clovis point.

The circumstances of blade finding and type of blade is much alike with what Years ago I was told by a friend in Tularosa New Mexico, who described it found on his property.

Wonderful time context

Reading Atlas of a Lost World during quarantine and this was a welcome, timely footnote. Thank you.

Nice correlation! Might the causation of both be a combination of water (coastal areas and inland rivers and lakes) and to a lesser extent geography (mountain ranges).