Earlier this summer, as I lay with my head on my boyfriend’s chest, I heard something odd. His heart — an efficient athlete’s organ that normally thumps fewer than 50 times per minute at rest— switched from its reassuring, steady bah-buhm, bah-buhm, bah-buhm to rapid staccato: bah-bah-bah-bah-bah-bah.

I lifted my head and asked if he’d noticed it. Pete said yes, it had happened before, and that sometimes his chest hurt and his arm tingled. I called my dad, a retired physician, and he said Pete should see a doctor as soon as possible. As Pete left for his appointment, I badgered him to not minimize his symptoms: “Make sure you say the words ‘pain,’ and ‘tingling,’” I said.

It took a while to get the workup scheduled. When she hooked Pete up to monitors on a treadmill to do a stress test, the nurse was incredulous. “You’re too young for this,” she said. Pete is 35 but looks much younger. In fact, he looks so young that I didn’t take him seriously when he first asked me out three years ago, at the start of a long, slow courtship. In May, when we attended graduation at the high school where Pete teaches science, someone mistook him for a student, congratulating him on his achievement.

The point is, Pete looks young and healthy. He is young and healthy. But his blood pressure has been abnormally high since his twenties— high enough that he needs meds — and the doctors don’t know why. Last month they gave Pete a heart monitor and instructed him to wear it for 30 days, to detect any abnormal rhythms. They also performed an echocardiogram, using soundwaves to image his pulsing heart. Two weeks ago, we sat at our kitchen table and opened a bland-looking envelope from the VA Medical Clinic which contained his echocardiogram results. Among the findings, it listed a congenital malformation of the heart called a bicuspid aortic valve.

When I write about medicine, I try to provide readers with cautious, heavily caveated information. Sometimes readers write to ask how what I’ve written applies to their own health, or that of their loved ones. I don’t know what to do with most of these emails — the pleas for information that could help a mother with Alzheimer’s disease, or explain why a child developed autism.

Sometimes I’ll explain that the patterns scientists find in large populations usually aren’t good at predicting what will happen to any given individual, or try to explain the difference between absolute and relative risk. But data comes alive through personal stories, and this can create problems. If one of my stories focuses on a person who did well in a clinical trial, for example, I risk creating the impression that what worked for one person will work for everyone.

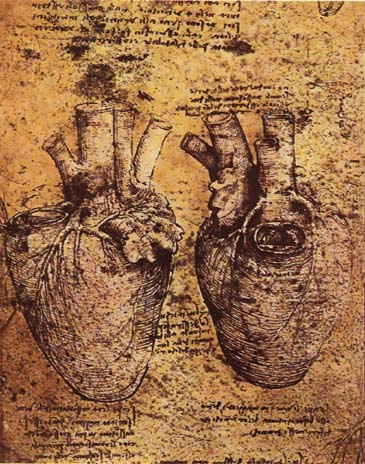

What is true about Pete’s heart? Suddenly I find myself in the position of readers who’ve reached out to me over the years, hungry for stories not about what is likely to happen in large groups of people over long periods of time, but what will happen to them. I’ve started brushing up on heart anatomy: the aorta is the main artery carrying oxygen-rich blood out of the heart. The aortic artery is kept separate from the heart’s left ventricle by a valve. This valve normally has three membranes called leaflets, which open and close with every heartbeat, preventing blood from flowing backwards.

In roughly 2 percent of the population — including, apparently, Pete — two of these smaller leaflets fused during embryonic development. Many people never know they have BAV, but it can cause problems over time. Among the most serious are a bulge in the blood vessel, called an aortic aneurysm, and a tear inside the aorta, or dissection.

We’re still waiting on Pete’s followup appointment. I’m trying to reign in my impulse to learn more about his condition, and wait for his doctor to interpret the literature. It’s tough — on some level I still believe I can stave off disaster through research and prophylactic dread. That’s the problem with stories. If you’re not careful, they create an illusion of certainty where none exists. Chances are he’ll be fine. Right?

Our experience with medicos has been decidedly mixed. Medicine is a woolly science, primarily I believe because the body is such an immensely complicated mechanism. We tend to look to our docs for answers, not realizing that what we’re getting are averages and trends and the voice of highly-localized experience. My wife’s Ob/gyn, for example, sees a lot of post-menopausal white stay-at-home moms so she frames each problem in the things that she has seen — the problems of post-menopause in a small slice of white sedentary society. Sometimes her diagnoses fit. Sometimes they don’t.

I don’t envy you guys this path. Good luck. Be your own medical advocates. Go ahead and do you research. But then run it by the docs and let them add their voices of experience on top of it. Averages and trends are sometimes right on the money.

Your usual generous and intelligent comment, Dave. Just to reassure you, I don’t think Emily’s in any danger of not running it by the docs.

Thank you both. I’m the designated Worrier and Researcher in this relationship (Pete is in charge of Sunny Outlooks, Risk Taking and Good Cheer), so I fully intend to tap every available resource. Meanwhile, Pete will be off riding his motorcycle and launching his kayak off waterfalls, no matter what the doctor says…

God I wish I were more like Pete. I am also the designated worrier. But you knew that already…

Designated Worriers Forever! We stand united, we stand against all worries and uncertainties, we never stop!