Saturday, March 31, was kind of a big day for the moon. It was full for the second time this month, making it a blue moon — the second of 2018. It was also the first full moon after the spring equinox, what’s known as the Paschal moon. The first Sunday after such a moon is designated as Easter, but only very rarely does Easter Sunday fall the day after that moon, making this one unique.

And there was another special reason. March 31 marked the passing of a milestone that means the moon will be bereft of humans for a little while longer.*

It was the deadline to capture the Google Lunar X Prize, a once-storied competition that pitted more than two dozen private companies against each other in a race to return to Earth’s satellite. Nobody went, and nobody won.

The competition, financed by Google, was announced in 2007 to worldwide fanfare. It came just a few years after the Ansari X Prize, for the first privately-built spacecraft to make it to space twice. The successful 2004 flights of SpaceShipOne captured public imagination — and $10 million for its designers and financiers. On the heels of SpaceShipOne’s triumph, a challenge to boldly go where only NASA had gone before seemed like a risky yet reasonable idea.

The Google Lunar X Prize offered up to $30 million in prize money, including a $20 million grand prize. The competition had fairly basic criteria: Safely land a privately funded spacecraft, move it one-third of a mile, and send streaming HD video back to audiences on Earth. Initially, 33 teams registered.

By 2014, when I wrote about the competition for Popular Science, the prize deadline had already been extended once, to Dec. 31, 2015. Just 18 teams were left. Of those, only a handful were truly strong contenders. The deadline was extended again and again, until finally last August, when Google said it would not move the goal posts past March 31.

In the end, only five teams remained: Hakuto, from Japan; Moon Express, based on the Space Coast in Cape Canaveral, Fla.; SpaceIL, based in Israel; Synergy Moon, an international collaboration; and TeamIndus of India.

Despite the competition’s sad-trombone ending, its organizers said it had some successes.

“We have sparked the conversation and changed expectations with regard to who can land on the moon,” said a statement from Peter H. Diamandis, the foundation’s founder and executive chairman, and Marcus Shingles, the chief executive. “Many now believe it’s no longer the sole purview of a few government agencies, but now may be achieved by small teams of entrepreneurs, engineers, and innovators from around the world.”

May be. Maybe. I suppose. One can dream, but for now, landing on the moon is still decidedly the province of a few government agencies. In 2013, China landed its Chang’e 3 lander and Jade Rabbit rover in the moon’s Sea of Rains, accomplishing what private industry could not. This year, India aims to send its own lander, and China plans to return. And President Trump and his administration say they really want Americans to go back, too. These will be government-funded efforts, all.

It will be interesting to see how the competition’s flameout affects future X Prize competitions, and other audacious exploration efforts. After all, each X Prize was built in the spirit of the first such successful competition, completed 81 years ago. You may not recognize the name Orteig Prize, but you certainly know the name Charles Lindbergh.

In St. Louis, where I live now, we have a scale replica of his famous airplane. The Spirit of St. Louis soars above the entrance of the Missouri History Museum. It is so named because the city, where Lindbergh flew the mail, helped finance his airplane and his trip. In 2004, a group of wealthy residents and philanthropists chipped in to fund the Ansari X Prize, too. Both prizes aimed to jump-start industries: In Lindbergh’s case, transatlantic travel, and in the Ansari case, private spaceflight.

Well, transatlantic travel certainly happened, and changed society forever. Private space tourism, not so much, although private space companies are certainly doing just fine these days. Private moon exploration, though — that one was a no-go.

There are several reasons why. Cost, obviously. Getting a ride to the moon was probably the biggest challenge; most rockets aren’t hefty enough to send something there, and the ticket is both hard to get and expensive. Then there’s the lack of rationale. Why do it? What’s the business case? You could argue that it would prove the moon is reachable through more than the wealth of nations, and that means people could go and prospect, and maybe strike it rich. But that’s still dubious.

I have another, cheesier reason. People were rooting for “Lucky Lindy”/Nazi sympathizer Charles Lindbergh and the Spirit of St. Louis. People were rooting for SpaceShipOne, dreaming of space tourism. Ultimately, a lunar rover with a corporate emblem just doesn’t carry the same weight as the colors and the hopes of a nation.

And so the deadline came and went, and nothing happened. The moon, for its part, did not notice.

* The moon does not know or care about any of this, of course. But I do.

—

Image credit: Top: A lunar eclipse. By NASA/Bill Dunford

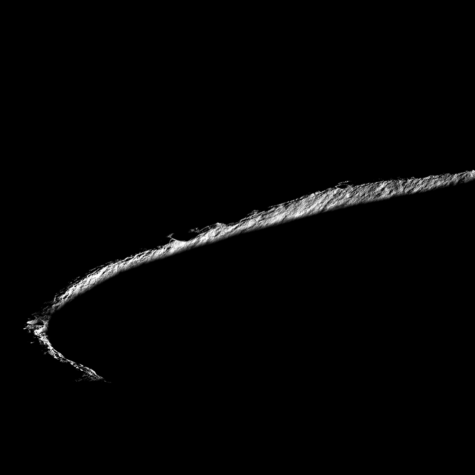

Middle: An oblique view of the rim of Shackleton crater at the moon’s south pole. By NASA/GSFC/Arizona State University

One thought on “We Did Not Go Back to the Moon, Because It Is Hard”

Comments are closed.