Today’s post is the first of a two-part series on homeopathy. Look for another tomorrow by LWON’s own Sally Adee.

Today’s post is the first of a two-part series on homeopathy. Look for another tomorrow by LWON’s own Sally Adee.

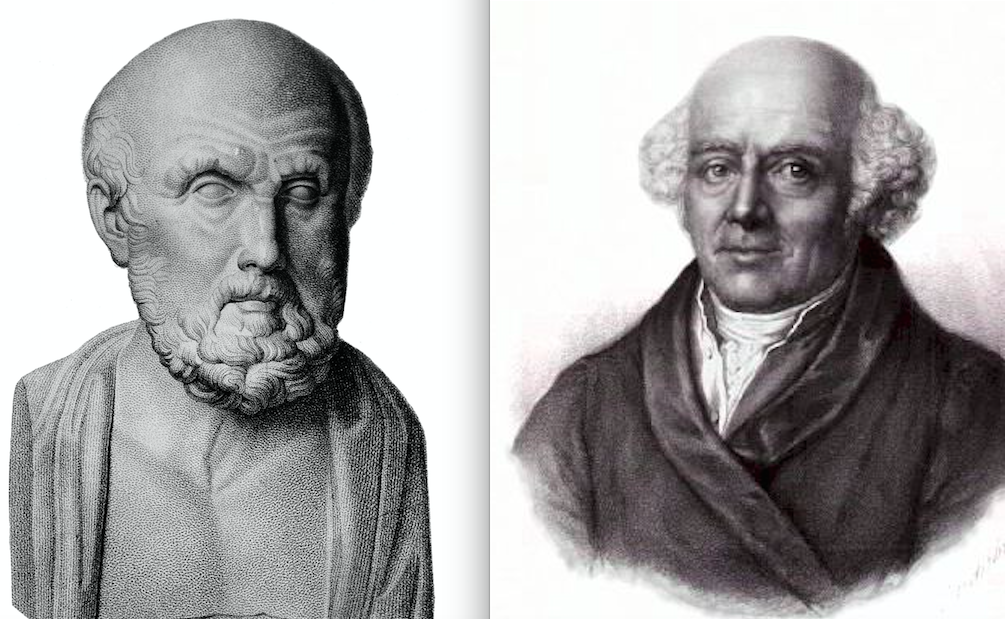

In 460 BCE, a rebel was born. Ruggedly handsome, fluffy hair that drove younger girls crazy and a gleaming bald pate that made the older ones swoon.

His buddies called him “The Father of Medicine,” “Ἱπποκράτης” or just “The Hippo.” His enemies called him that “that bald guy who gets angry whenever I beat my patients with a flaming branch to appease the god Hephaestus.”

He was Hippocrates of Kos and he rocked the Western world like almost no other human being in history.

Twenty-two centuries later, another rebel was born just a short 1,000 miles to the north. Samuel Hahnemann was equally popular with the ladies (or lady – he had eleven children) and had similarly luxurious hair on some of his head.

What did these two rebels have in common? It turns out quite a bit.

Allow me to step back a few thousand years. Before Hippocrates hit the scene, the ancient Greeks believed diseases were caused by angry, sociopathic gods who took an almost pathological interest in humans and had washboard abs. As such, treating a patient generally meant treating his/her relationship with the gods.

This might mean praying to the gods, taking herbs and asking your buddy to pour wine on your wound. Or it might mean praying to the gods, drinking special teas and cutting your buddy into little pieces as a sacrifice.

Hippocrates’ father was a physician and he slowly became disgusted with the medicine of his day. Healers were as much holy men as they were physicians and their track record was less than stunning. Hippocrates was the first to posit that disease was not a product of the divine but of the body. Given that simple fact, he then came up with two ideas that changed the world forever.

The first was that nature itself can actually cure a person better than any human hands. And that most often what is needed are not elaborate rituals or toxic herbs but bed rest and time.

This breakthrough – that sometimes the best medicine is no medicine at all – was so important that it’s still the guiding principle for all medicine. Essentially his message was, “hey, the the last thing you want to do is make things worse.” Sometimes nothing is better than something.

Fast forward to the 18th Century. Samuel Hahnemann was also a brilliant man disgusted with the physicians he saw all around him. Fluent in eight languages and poor as a church mouse, Hahnemann had an insatiable intellect and a habit of self-experimentation.

Much of the medicine of his day was descended from what is known as humoral medicine (or Ayurveda, depending on your continent), which coincidentally was Hippocrates’ other big idea. It professed that instead of being governed by adulterous mountain-dwelling beings, disease was the result of an imbalance between the four most important fluids, or humors, in your body.

The humors were: Blood, phlegm, black and yellow bile (or air, water, earth and fire). Why bile got two spots and urine, tears, pus, or sweat got cut from the roster we may never know. Clearly bile was just that awesome.

The idea is actually not too distant from modern Chinese Medicine, which boils the body down to metal, water, earth, wood and fire. Like TCM, humoral medicine was based on the spirit or nature of a cure as much as its ingredients.

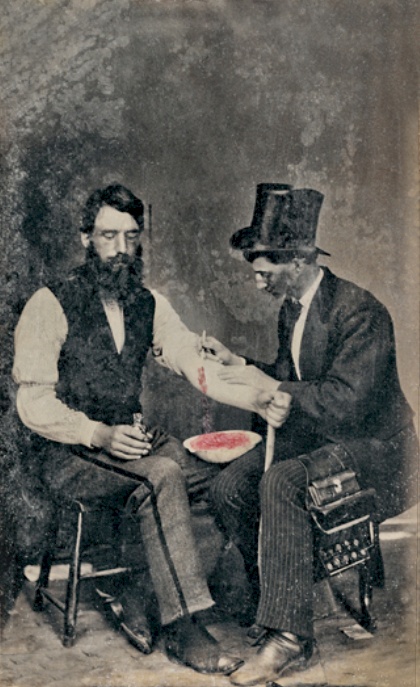

By the time Hahnemann came along, the humors themselves were out of fashion but many of the treatments inspire by them were not. The young doctor was especially repulsed by the common practice of bloodletting which was used to treat just about everything under the sun and probably killed as many people as it healed.

Like Hippocrates, Hahnemann also had two strokes on genius, one similarly correct and the other less so. The first was that unclean conditions contributed the spread of disease. This may seem obvious to us today but without the knowledge of cells or germs, it was actually quite insightful. After all, these were people who rubbed manure on open wounds to heal them.

The second was homeopathy. It’s well established that all geniuses have a catchphrase. “I think therefore I am,” “E=mc 2,” “To be or not to be.” If Hippocrates’ catchphrase was “Do no harm” then Hahnemann’s was “Like cures like.”

Hahnemann noticed that when he took the malaria drug quinine when he was healthy he got malaria-like symptoms. What if, he thought, quinine cures malaria because it has the same properties? Then he went a step further. What if water actually remembers those properties even after the substance has been diluted out?

And homeopathy was born. As with TCM or humoral medicine, a modern homeopath will diagnose a disease based on its elemental nature – cold, hot, solid, ephemeral – rather than biology. Then she will prescribe what amounts to water or sugar pills. Because of the incredibly high levels of dilution, there is no actual medicine in homeopathic medicine – only the memory of medicine. That’s why you cannot overdose on it, measure it and, perhaps not surprisingly, why it doesn’t perform any better than a placebo during trials.

And homeopathy was born. As with TCM or humoral medicine, a modern homeopath will diagnose a disease based on its elemental nature – cold, hot, solid, ephemeral – rather than biology. Then she will prescribe what amounts to water or sugar pills. Because of the incredibly high levels of dilution, there is no actual medicine in homeopathic medicine – only the memory of medicine. That’s why you cannot overdose on it, measure it and, perhaps not surprisingly, why it doesn’t perform any better than a placebo during trials.

And yet homeopathy is one of the most popular types of alternative medicine in the world, especially in Hahnemann’s home country of Germany. Over 50 percent of Germans use it and 75 percent of German doctors prescribe it. People report overcoming crippling pain, depression, anxiety and a host of other diseases using homeopathy.

Sometimes nothing, it seems, is better than something.

So what was it that allowed homeopathy to become so popular? It’s just not possible that so many hundreds of thousands of people could wrong about something like that. What’s the driving force behind homeopathy? For the answer, you’ll have to wait for Sally’s post tomorrow.

But I will give just this one three-word hint: Massive, worldwide conspiracy. Really.

Photo Credit: Creative Commons, Wikimedia, Shutterstock

> It’s just not possible that so many hundreds of thousands of people could wrong about something like that.

This sentence convinced me that the entire post had to be a joke. Looking forward to the punchline in part two.

Nick, everyone knows that if a thing is popular it must be true. Unless, gosh, unless there is something else at work here. I only hope Sally can clear it all up.