Stephen Kress has studied Atlantic puffins for more than forty years, so you might think that he knows everything there is to know about them. He’d be the first to admit that he doesn’t. Until very recently, in fact, neither he nor anyone else even knew where the little rascals were most of the time.

Puffins used to be common in Maine, but the population was almost wiped out by hunters in the early 1900s. When Kress, a wildlife biologist, arrived in the state in the 1970s, puffins lived on only one island. At the time, most biologists thought seabirds had an unbreakable connection to their birthplaces, but Kress wondered if young birds could be taught to accept another island as home. He and his fellow members of the Audubon Society-sponsored Project Puffin transplanted puffin chicks from Nova Scotia to Maine’s coastal islands, spent a summer raising them by hand, and watched as they left for the open ocean, hoping that they would eventually return to Maine to breed.

The experiment paid off: After several years, the birds began to trickle back to the Maine coast, and soon they started to raise their own chicks in the islands’ rocky crevices. Today, more than 600 pairs of puffins nest along the coast each summer, and the techniques Kress and his team developed are used to restore seabird populations all over the world. But adult puffins spend just four months of the year nesting on coastal islands; the rest of the time, they’re at large on the open ocean. Project Puffin had restored puffins to Maine, but it could only offer the birds part-time protection.

Beginning in 2009, Kress and his team started fitting a few birds with geolocators, hoping to solve the mystery of the puffin’s winter whereabouts. The first year, the birds carrying geolocators returned to Maine, but failed to breed; the gadgets were too heavy. When the researchers tried a smaller, lighter model, it leaked. Last spring, after 19 healthy birds returned to Maine with functioning geolocators, Project Puffin finally had enough data to map the puffins’ path. (Geolocators have also been used to track the migration of puffins from the British Isles into the North Sea and the Atlantic.)

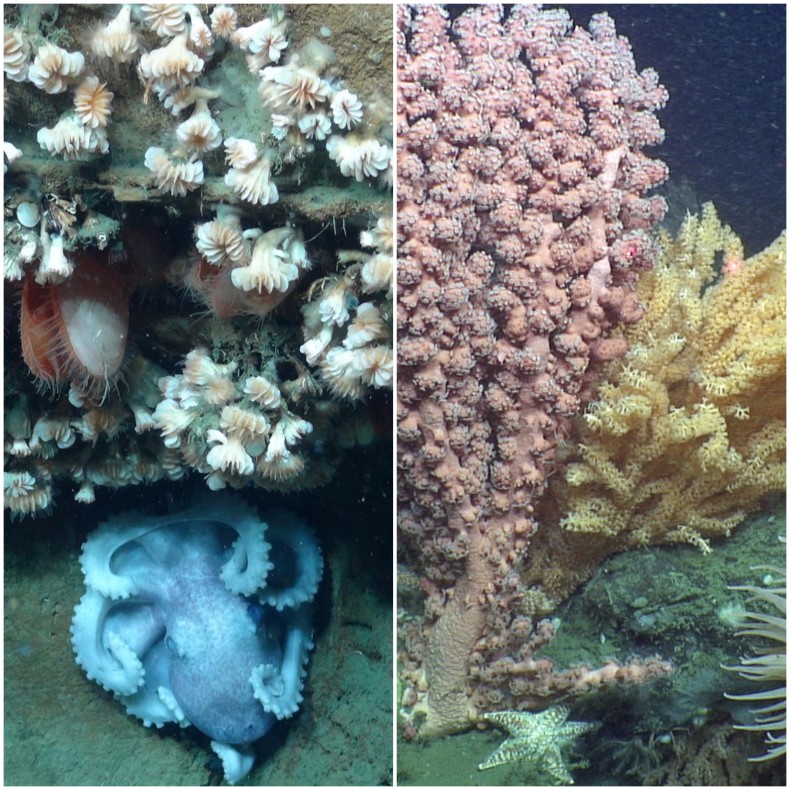

In late summer and early fall, Maine’s Atlantic puffins head north to the Gulf of St. Lawrence in Canada. By November, most of them have turned south, and settled in about 200 miles off the coast of Cape Cod. They spend most of their time floating over the continental slope, in an area known for its deep, biologically productive canyons: in 2013, a remote-operated vehicle deployed in the canyons by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration brought back photographs of colorful coral, sea anemones, octopi, and one illegally cute bobtail squid. It’s such a diverse place that this fall, a coalition of environmental groups called on President Obama to protect it from overfishing and energy development as part of a marine national monument.

In late summer and early fall, Maine’s Atlantic puffins head north to the Gulf of St. Lawrence in Canada. By November, most of them have turned south, and settled in about 200 miles off the coast of Cape Cod. They spend most of their time floating over the continental slope, in an area known for its deep, biologically productive canyons: in 2013, a remote-operated vehicle deployed in the canyons by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration brought back photographs of colorful coral, sea anemones, octopi, and one illegally cute bobtail squid. It’s such a diverse place that this fall, a coalition of environmental groups called on President Obama to protect it from overfishing and energy development as part of a marine national monument.

In recent years, rising water temperatures in the Gulf of Maine have altered the size and abundance of fish available to puffin parents, sometimes with devastating effects on nestlings (in 2012, one common species of fish grew too big for puffin chicks to swallow, and many young birds starved). Now, as Project Puffin follows its wide-ranging birds, it may be able to track ocean and fisheries conditions further afield—for the puffins’ benefit, and for ours. “The project started out as a way of learning restoration methods, but now, the puffins are telling us a lot about the changes in the ecology of the region,” Kress says. “They’re like a fishing fleet—every day, they’re out there. They’re great little monitors.”

Top photo: Atlantic puffin on Maine’s Eastern Egg Rock by Fyn Kynd Photography. Creative Commons. Bottom photo: Images from NOAA’s 2013 Northeast U.S. Canyons Expedition.

I am studying animal behavior and have a particular interest in Atlantic puffins. Last summer, I did a field observation report on these hearty little birds. They are endlessly interesting! Thanks for spreading the word about them and the need to protect their migratory fishing grounds.