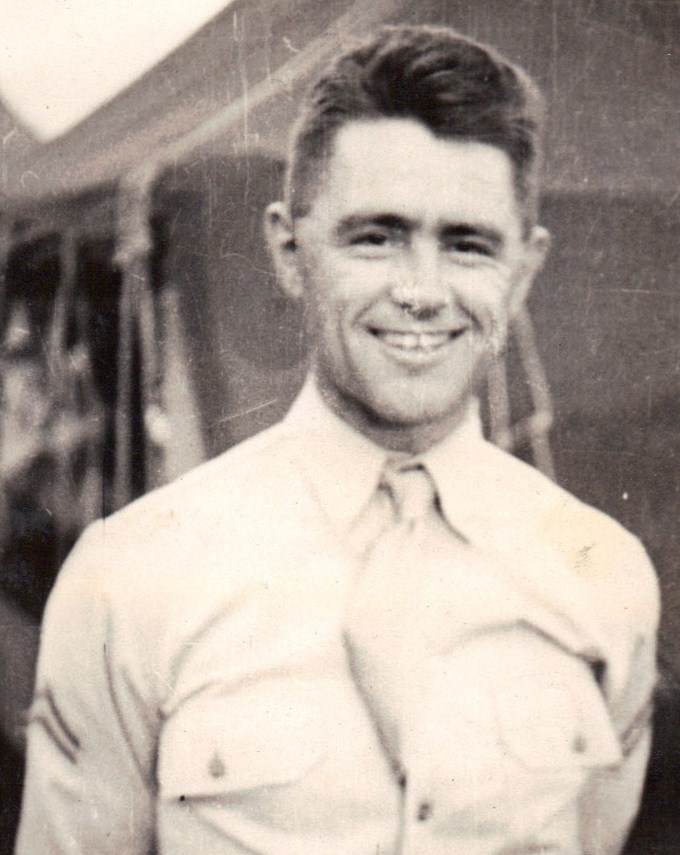

This post first ran May 28, 2012. Uncle Bundy has since died — at a nice old age with his family around him, but still — and when I think about soldiers and Memorial Day I always think about him, I’m not sure why: he didn’t talk about the war, maybe because he stood so straight.

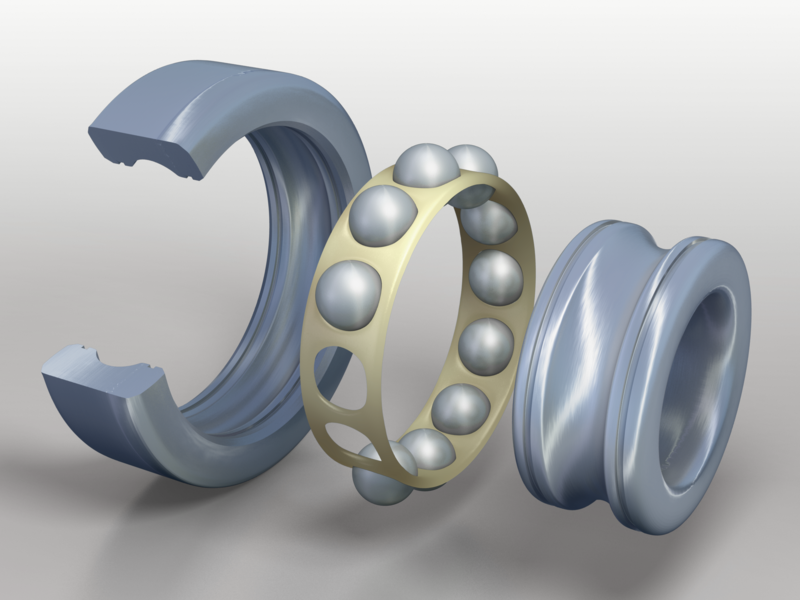

It’s Memorial Day in the U.S. but this is not a war story. It does have a little war in it, but the real reason I’m writing it is because of this ball bearing my uncle had. My uncle’s name is Leverne, some of his buddies call him Vernie, all his relatives call him Bundy – no reason for that – and he’s always been a mechanic. One summer day a long time ago, he was out in his garage working on a car and I was watching him. “Look at this,” he said, “it’s a ball bearing.” It was a grooved ring, and running in the groove were little metal balls. “I just greased it,” he said, “and look how pretty it goes.” He ran his finger over the little balls and, one after another, they turned smoothly and easily in their groove. “Isn’t it pretty?” he asked. No, it isn’t, I thought, but I didn’t answer. I was in high school and an English major. It’s greasy and dirty, I thought. Poetry was pretty, not ball bearings.

Bundy was a farm boy who went to high school, then in November, 1942, joined the army. He was sent first to the University of Utah, then went back to regular duty. Then he requested to be sent to the Fort Sill Motor School, then went back to regular duty. Then he requested to be sent to the 668th Field Artillery School, then went back to regular duty. Then he requested to be sent to the Schofield Barracks Motor School in Hawaii, and he learned to be a mechanic.

In 1944, he got on a Liberty troop ship, a little hollow tub short enough and the Pacific waves big enough that the ship went up one side of a wave and down the other while the seasick troops lined up along the deck and threw up over the side. The ship was headed for the Philippines, to the battle of Leyte in which 3,000 Allied troups and 10,500 Japanese troops were being killed. By this time Bundy wasn’t really mad at anyone and didn’t want to fight; and anyway Leyte turned out to need materiel, not troops; and besides the war was ending, so Bundy was just as glad when the Liberty ship turned around and went to Oahu, where he spent the rest of the war.

He came home to Illinois in November, 1945. He and Mitzi, his new wife, lived in an unheated upstairs room in his sister’s house. He got a job fixing cars and tried to figure out a place to live. He found a little octagonal house that had been built for either hired hands or pigs, and bought it for $2,300 which he borrowed from his mother. The house was too far from work so he bought a lot nearer by, and then he measured up the house and measured up the lot. Next he dug two rows of post holes and in the holes he stuck stove pipes which he filled with concrete, and this would be a foundation. Then he asked his two brothers and his brother-in-law if they’d be willing to help move the house; and next he asked a customer at work if he could rent the customer’s flatbed truck for a Saturday at the going rate of $3 an hour. His plan was to raise the house enough to back the flatbed under it.

He remembered seeing some 30-foot timbers somebody had left out along Route 66, and he and his brothers went out and picked them up. They brought the timbers back to the house and with two hydraulic jacks, jacked up first one corner of the house and wedged a timber under it; then jacked up another corner of the house and wedged a timber under it, then went back to the first corner and jacked up the timber and wedged another timber under that one; and pretty soon the house was perched on the timbers up higher than the truck. Then they backed the truck under the house, timbers and all, and headed out — Bundy stood on the roof to lift up any telephone or electric wires. When they got to the lot, they backed up to the foundation, unloaded the house, trimmed it up, and reversed the jacking-up process, removed the timbers, and rested the house on its foundations. It worked exactly as planned. Bundy paid the customer $9 for three hours rental, plus $1 tip.

Bundy and Mitzi lived in the house for five years, then sold it to his mother and moved to a house that could fit the six kids they eventually had, and where they still live. Bundy kept being an auto mechanic and by the time he retired, he owned his own garage. He told me in the 1970’s to hold on to the Dodge slant-six but for my next car, give up and buy Japanese because otherwise Detroit wasn’t ever going to learn. He’s 91 now and fairly creaky but is as bossy, opinionated, righteous, and impressively, ingeniously, precisely competent as he ever was.

Four months before Bundy got out of the service, the war had ended with the atomic bomb. That bomb has famously been called “technically sweet.” Technical sweetness is the perfect match between form and function, between a technology and its purpose. Technical sweetness is the satisfying mental click of a thing that’s exactly what it should be and nothing more. Technical sweetness is highly aesthetic and utterly compelling. The U.S. has always been good at technical sweetness, both in training people in it and doing it, for both ill and good — because like other principles, it intrinsically has two sides.

Four months before Bundy got out of the service, the war had ended with the atomic bomb. That bomb has famously been called “technically sweet.” Technical sweetness is the perfect match between form and function, between a technology and its purpose. Technical sweetness is the satisfying mental click of a thing that’s exactly what it should be and nothing more. Technical sweetness is highly aesthetic and utterly compelling. The U.S. has always been good at technical sweetness, both in training people in it and doing it, for both ill and good — because like other principles, it intrinsically has two sides.

Over the years, I’ve interviewed several whip-smart country boys who had gone into the service, had gotten a technical education, worked on one bomb or other, then come out of the service and gotten educated as physicists and gone on to stellar careers and even a Nobel Prize. I also interviewed ones who didn’t get educated but got jobs as lab technicians; or they got educated and became all kinds of engineers; or they did or didn’t get educated but they write scientific software.

That is, between the time I stood in my uncle’s garage and now, I learned to appreciate technical sweetness. And as technically sweet as a bomb and much, much prettier? A ball bearing.

__________

Photos: Bundy – unknown; ball bearing – Niabot

Uncle Bundy understood technical sweetness better than any other man you will ever meet.

Thank you, I finally have a phrase for that feeling I get when I look at well-constructed machines. Technical sweetness, that’s just it.

Full disclosure – I am Ann’s brother (thanks, Ann, I didn’t know some of those things about Bundy). It wasn’t just intuition with Uncle Bundy, though he has that in plenty. He was and is pretty far out there on the whip-smart continuum. How else do you describe a guy with his education level who could puzzle over my college physics text book for a few minutes, and then explain some vector calculus that my teacher could not explain well? And do you want to mention Bundy’s fascination with Fermilab, Ann? Uncle Bundy could easily have been one of those guys Ann describes in her last paragraph, and those kinds of people are pretty awesome when you run into them.

Old Geezer: If I didn’t know better, I’d strongly suspect you of being Uncle Bundy. Maybe you’re somebody else’s uncle?

Jennifer: You probably know the provenance of that phrase. Robert Oppenheimer said it about the bomb. It still gives me shivers.

Bruz: I always wished he’d come back from the war and gone to science school, not necessarily for his sake but so I could watch his smoke.

Ann: yes, I followed the link and in that context it’s beyond creepy. But it still fits what I feel when I watch machines and until now I never could really describe it.

Definitely not Uncle Bundy, but would love to spend an afternoon with him (especially in his shop).