There is a much-fêted relationship between a writer and his editor. Less often is it mentioned that a writer often keeps up a second backchannel with folks from the business side of a publication, dealing with invoices and working out logistics. With smaller pubs you may actually be talking to the publisher, as is the case here. It’s an awkwardly mercenary part of the job, but occasionally, one can find a way to elevate it.

The correspondence below spanned 2015-2021.

<Contract #1 Signed>

Quick question about invoicing: [Contract #1] was assigned and filed at 800 words, then edited down to something like 680 words. Do I invoice for the original $X or see what the word count comes to and invoice for the per word rate? Also, is this a question for my editor?

We pay the assigned rate 🙂

Hooray! Here is the invoice — I’m told the piece is expected to run tomorrow. Thanks.

📎 invoice

Thanks, Penny. I’ve passed this on for payment. Fascinating story!

Have a great day.

<Contract #2 signed>

It seems I’m always hitting you up for money, like some sort of dead-beat sister. This one’s for the piece about the invention of pottery, coming out now-ish.

📎 invoice

Brothers always spoil their sisters, right, dead-beat or otherwise? So how about I increase your payment to $Y? Your published story was 658 words, well in excess of the 500 contracted for so we’ll pay the overage. Your invoice is a Word document, so I can just change it myself, no need to send a revised invoice. Have a great day.

Yes, I WILL have a great day now. That’s a much appreciated bonus. Thank you.

<Contract #3 signed>

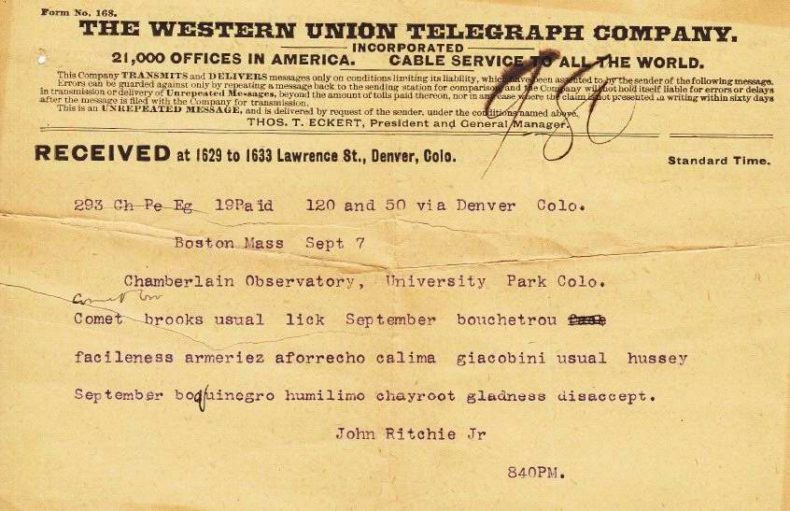

DEAREST BROTHER -(STOP)- HAVE EXHAUSTED ALL PREVIOUS FUNDS AT THE CRAPS TABLES -(STOP)- PLEASE WIRE MORE -(STOP)-HAVE A HOT TIP ON A RACE HORSE -(STOP)- YOUR DEAD-BEAT SISTER

📎 invoice

DEAREST SISTER -(STOP)- ANSWER TO YOUR GAMBLING PROBLEMS FOUND -(STOP)- ALL IS EXPLAINED IN MESSAGE SCRATCHED IN STONE AT BASE OF N MOST TREE ON ISLA DE MARGARITA -(STOP)- PAYMENT BURIED UNDER ROCK -(STOP)- PRAYING FOR YOUR SALVATION -(STOP)- YOUR DEAREST BROTHER

<Some French publication I’ve never heard of emails, asking to syndicate my latest piece about the Dutch East India Company’s use of postal stones, referenced above, and CCing the publisher. I strike a deal with her. But then the publisher responds to ask her details on what she’s offering.>

I’m so sorry — I thought they had been referred by you and were simply CC’ing you to indicate this. I went and approved it, but of course that’s not binding unless you sign off! I’ll let you take it from here.

I am probably fine with it, but I didn’t see any further details. Did they provide you terms?

No, she didn’t give any details on that. I unthinkingly quoted her my usual syndication fee of $X, then she came back at $Y and I said fine. But it’s so soon after publication — you probably own it for a year or so? Maybe I can sell them the Brooklyn Bridge instead. Anyway, now you know their price range!

$Y is about right, though it can depend on exactly what they were planning. We do technically have exclusivity for the first 6 months, with a revenue sharing for reprints. But we don’t have any real expectations of generating big revenue from syndication, so you go ahead and keep the money. We’ve only had one other paying syndication, so far, and we let that author keep the money too. So, dinner on me, deadbeat sister 😉 Happy Easter!

That’s awfully generous of you, and I’ll try not to sell any more of your stuff. This comes just in time — remember that hot tip I got at the racetrack? Nobody told the horse. Happy Easter back at you.

<Contract #4 signed>

DEAREST BROTHER -(STOP)- ATTEMPTED TO BUILD LAND BRIDGE OUT OF CLAMSHELL MIDDENS -(STOP)- NOW MIRED THREE FEET AWAY FROM CALVERT ISLAND -(STOP)- PLEASE SEND FUNDS FOR A TOW TRUCK -(STOP)- YOUR DEAREST SISTER

📎 invoice

DEAREST SISTER -(STOP)- TOW TRUCK IS BUSY TRYING TO EXTRICATE REPUTATION OF RYAN LOCHTE AND OTHER US SWIMMERS -(STOP)- I HAVE A LINE ON SOME KIND HUMPBACKS WHO MAY BE WILLING TO RESCUE YOU -(STOP)- SIT TIGHT -(STOP)- YOUR DEAREST BROTHER

PS HOLD YOUR BREATH IF THE TIDE COMES IN -(STOP)-

<Years pass>

DEAREST SISTER -(STOP)- IT HAS BEEN SO LONG, THE FAMILY HAS BEEN WORRIED. -(STOP)- WE’VE MISSED YOU SO -(STOP)- MONEY IS ON OFFER TO BRING YOU BACK INTO THE FOLD BUT WE AREN’T SURE WHERE TO SEND IT -(STOP)- DO YOU STILL LIVE AT [ADDRESS] -(STOP)- CANT WAIT TO HEAR OF YOUR ADVENTURES. -(STOP)- YOUR DEAREST BROTHER

ARE YOU OUT THERE DEAREST SISTER -(STOP)- NO ANSWER TO MY LAST EMAIL. ADVISE.

DEAREST BROTHER -(STOP)- APOLOGIES FOR THE SLOW TRANSMISSION -(STOP)- RECENTLY SPRUNG FROM EMIRATI CAPTIVITY BY A CRACK TEAM OF SCUBA DIVERS -(STOP)- PREVIOUS ADDRESS CONFIRMED AS CURRENT -(STOP)- YOUR DEAREST SISTER

<Contract #5 signed>

DEAREST BROTHER –<STOP>– MOB GOT WISE TO MY MONOPOLY MONEY RACKET –<STOP>– TOOK REFUGE IN A FOREST GARDEN –<STOP>– SUBSISTING ON CRABAPPLE AND HAZELNUTS –<STOP>– BEAR HAS TAKEN UP RESIDENCE ALSO –<STOP>– PLS SEND FUNDS FOR BEAR SPRAY –<STOP>–YOUR DEADBEAT SISTER

📎 invoice

DEAREST SISTER –<STOP>– MONEY FORTHCOMING –<STOP>– HAVE YOUR BANK DETAILS CHANGED –<STOP>– LAST BANK WE HAVE FOR YOU WAS IN THE GREAT WHITE NORTH –<STOP>– NEW BANK FORM ATTACHED –<STOP>– FEED THE BEAR THE CRABAPPLES AND STAY ENJOY THE HAZELNUTS –<STOP>– YOUR DEAREST BROTHER

DEAREST BROTHER–<STOP>–BANKING DETAILS REMAIN THE SAME –<STOP>–OPENED ACCOUNT IN GREAT WHITE NORTH DURING FAILED GOLD RUSH BID AND NEVER CLOSED IT –<STOP>–THX FOR CHECKING–<STOP>–D.B. SISTER

<Contract #6 signed>

Your deadbeat sister is on her feet and has acquired an email address. I see that it was actually on this day in 2015 that you started helping me out of various scrapes. To be real for a second, I’m off to seek my fortunes on Wall Street, having taken an analyst position for a New York investment fund. If I turn out to be employable and manage to hold down the job, I’m unlikely to be writing freelance again.

It’s been a pleasure doing business with you.

Warmly, Penny

p.s. invoice attached.

📎 invoice

Oh my gosh, sister! Good thing you said “to be real” because that almost doesn’t sound real 😁. Congrats on the job and good luck with it!

I’ve passed your invoice on for payment.