My in-laws are visiting from the East Coast and we’ve had some days to explore. The local bar in our five-hundred-person town is a must-see, its sleek wood and mirrors more than a century old, and the old mountain-mining town of Telluride is forty-five minutes away for window shopping and looking for famous people. The bulk of our days, however, we’ve spent with much older points of interest. If you’re coming all the way from the other side of the continent, I wouldn’t want to be frivolous.

My wife planned most of the tour, a whirlwind of sun-filled valleys and cliffs. The desert of southwest Colorado in October is at its peak, green from summer rains, warm but not searing. We mince our way up canyons, over boulders the size of bedrooms, and follow dry washes and backroads, our truck loaded to take us to the next stop and the next.

A man unlocks a gate near a permanently closed trading post and lets us through. A mile or so down the road, we park under cottonwood shade. Near the outbuildings of a desert ranch, the in-laws spot a boulder across the road pecked with a fifteen-hundred-year old anthropomorph. They’re getting good at spotting images, recognizing the style, Basketmaker Culture.

The boulder is the size of a cottage and it has rock art on every side, bighorn sheep, lightning-like snakes, and human figures with plumes and lines coming out of their heads. We have the usual conversation, surmising headdresses or hunts, a dialogue that has to happen at rock art panels.

I came to this family saunter fresh off of a teaching gig for Crow Canyon Archaeological Center in Cortez, CO. This had been a field program in the Utah backcountry, in the contested and soon to be restored lands of Bears Ears National Monument, just over the horizon from where we live. I taught with an Anglo museum curator, a Hopi archaeologist and tribal member, and a scholar from the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe. A dozen participants followed along as we walked to rock art and ruins, which the Hopi archaeologist said were not ruins, not abandoned. They were still on the Hopi map, places very much alive.

The Hopi archaeologist I taught with would say these petroglyphs were spirit people, ancestors, the ones who carried prayers. I’ve also heard them called personifications of clouds, where instead of seeing a rockface of people, you are seeing thunderheads marching toward you, rain bringers.

Continue reading

If you study the breeding habits of a stout gray seabird called the rhinoceros auklet on a couple of islands in Washington, a field season typically lasts from May until August. Come fall, then, you have a choice: you can either dive into the data and analysis and statistical whatnot, or you can spend some quality time with the photos you took during the field season, and so try to make it last a little longer.

I usually opt for the photos. I say this even though I’m not a very good photographer. My portfolio consists mostly of run-of-the-mill landscapes and seascapes. Often those -scapes are filled with dots. (“Are those supposed to be birds?” my daughter asks.) No matter. I just like to look at the auklet’s islands. One, Protection Island, is about two miles off the north coast of the Olympic Peninsula, in the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Here are a few of the several hundred shots I have snapped of it over the years.

In regard to the wildness of birds towards man, there is no other way of accounting for it… many individuals… have been pursued and injured by man, but yet have not learned a salutary dread of him.

Charles Darwin, On the Origin of Species

Darwin's Finches All right, fine, the first few birds Could not have seen this coming. They saw only dark shapes—large, lumbering, branch-winged birds Tipped with tufts of down. Of course the little birds were curious. Of course they believed the branch-wings Were benevolent. And you’re right: Once those first birds had been grabbed, Necks twisted, No, they couldn’t have gone back To warn the others. But the finches just kept coming, Bird by trusting bird, And the men kept killing them, And the flock kept thinning. You might think at some point One bird might say to another, You know, there’s something strange About that beach— The birds who go there Never come back And maybe One bird did say this, And maybe The warned bird went anyway. I guess I understand.

*

Image by Flickr user Brian Gratwicke under Creative Commons license

What can I say about Kate Horowitz, our newest LWON member, whose debut piece is about to drop on Monday? She’s insanely creative and smart, generous as can be, and has a truly unique voice that draws you in and holds you tight. She’s a science writer, essayist, and poet, for starters; I promise her posts will be like nothing you’ve read before–and just what you need right now. Please jump up and down with us in honor of her arrival!

_____________

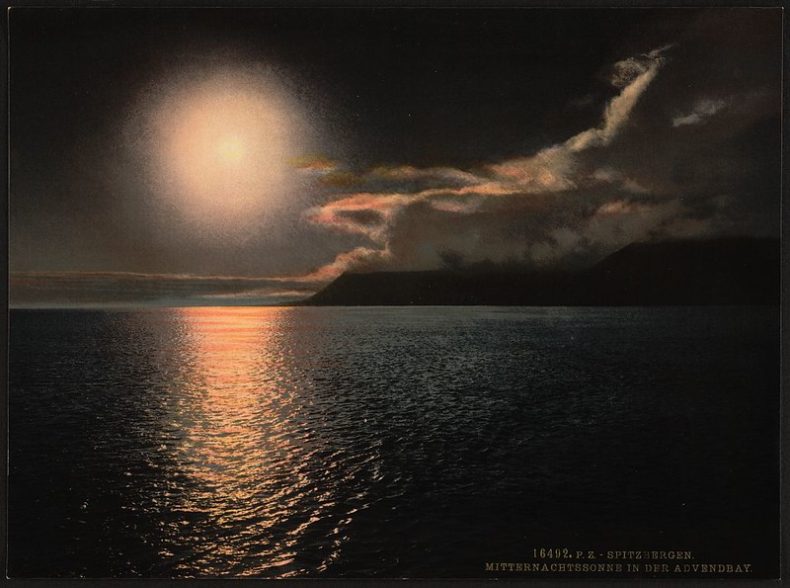

Photo from Public Domain Review

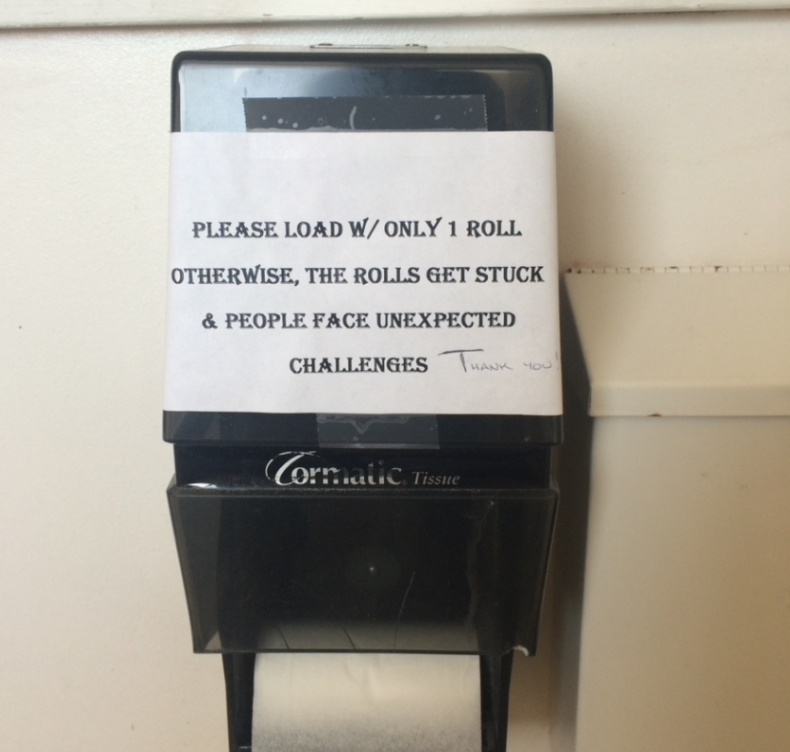

As I’ve moved through life, there are an unimaginable number of things I’ve seen or heard, briefly enjoyed, and then summarily forgotten about. For those of us with awful long-term memory, this is the joy in rereading books: it’s like reading it for the first time. There are things I’d like to remember better, and then there are the insignificant snippets that have inexplicably stuck with me, the things I’ve turned over in my head again and again. (The sign above, for instance, is a rich text I encountered in a former military base bathroom in 2015. I still think about at least quarterly.)

One of those things: a story a friend told me about a statistics class in college. The topic was probability. “I don’t get it,” a classmate said. “Everything is just 50/50; either it happens, or it doesn’t.”

I’d be lying if I said my first instinct wasn’t to laugh. How absurd! Probability is real! We use it all the time! (The assumption that probability is self-evident is why ditzy Karen’s weather forecast in Mean Girls lands: “There’s a 30% chance it’s already raining.”)

But the more I’ve thought about it, the more I understand my friend’s classmate. The factors underlying probability are often invisible, murky. Take coronavirus, for instance; it’s not 50/50 whether you’ll get COVID, but whether your risk level is 90% or 10% depends on a whole slew of factors: the rate of transmission where you live, whether you’re wearing a mask, and if you’re vaccinated, among other things. There are calculators that try to quantify that risk; this one says my county’s current risk level is 36%. This type of data is important for researchers, epidemiologists, public health officials, and other people in a position to make decisions about COVID policy, but what, exactly, are citizens supposed to do with this precise percentage? I’m vaccinated, I try to avoid crowds, I wear a mask indoors, and I wash my hands frequently. I’m not sure what else to do. It feels a bit 50/50; either I’ll get it, or I won’t.

I’ve never met the 50/50 person, and probably never will, but I’ve spent a not insignificant amount of time thinking about what they must be like. It is easy to assume the worst of them or what they represent, just as it is always more comforting to find ways to puff yourself up at someone else’s expense. What an indictment of this country’s math and science education! This type of STEM ignorance is exactly what got us into this whole COVID mess in the first place!

But I have grown to admire this person. I never spoke up in college for fear of looking stupid, and it took me another five years to realize it was ok to ask questions about things I thought I should already know, so I’m impressed that they asked this in class at all. I’m also a little envious of their ability to entertain a world view so rooted in the present. Perhaps by now this person has a more robust understanding of probability, but imagine believing everything is 50/50: wouldn’t that be freeing, in some ways? Imagine the mental calculus you’ve expended trying to determine your odds of getting that job, landing that pitch, getting in a run before it starts raining. Some things are unknowable; others are out of your control. Maybe we’d be better off imagining those things are 50/50: either they will happen, or they won’t.

This week I received an email from an R&D engineer at Canada’s National Research Council. Hossein Babaei and his team in the Ocean, Coastal and River Engineering division have been doing computational modelling of the ways in which the ice in an ice road deforms under the tyres of slow-moving versus speeding trucks. They then compare that modelled behaviour with what they can see from satellite imagery. He says that radar from 400 km away in orbit can sense those waves under the ice, even though on the ground, it is only perceptible through the ice’s groaning and crackling noises.

Hossein had come across the post below from more than a decade ago–I visited the ice road construction project in 2007–and he wanted to follow up on a claim I had made that the truck that follows a speeding vehicle has more risk of going through the ice than the speeder himself. He wanted to investigate it further, but sadly I don’t still have my notes. If you enjoyed the post, too, and want to know more about how things really work, I highly recommend Hossein’s paper on the subject.

In the wake of the smash hit History Channel series Ice Road Truckers, now in its fifth season, my town has become an unlikely celebrity. The reality of the ice road is quite different from the documentary series’ portrayal, and I thought I might break down the mechanics of the thing, having spent quite a bit of time on it.

A private road jointly run by mining giants Rio Tinto, De Beers and BHP Billiton, the Tibbitt-to-Contwoyto winter road is the longest of its kind, at 568 kilometres (353 miles) up into the Canadian tundra. Eighty-seven percent of the ride is on lake ice, and there are 64 portages between lakes. It’s open for only two months every year, but serves as the main conduit for bringing fuel and supplies up to four diamond mines. A land link offers transport at a fraction of the cost of air freight.

It all starts in July, when helicopters survey the route from the air, checking for changes in terrain and currents, and mapping the area in detail. One year’s winter-road route is never quite the same as the last.

In November and December the helicopters are launched again, flying the route using ground-penetrating radar to measure ice thickness. The builders then send out a light tracked vehicle, which gingerly creeps onto the ice to validate thicknesses.

If it’s touch-and-go, they’ll follow up with amphibious Hagglund vehicles that don’t mind getting wet if the ice fails. There’s an escape hatch in the top and a pair of protruding arms designed to stop any falls through the ice. Their first task is to plow the road of snow, allowing the cold to penetrate into the ice. Plowing is only the beginning. This is no pick-up hockey rink: By the height of the season the road has to be more than a metre thick. So December and January sees the 160 construction employees – mostly farmers whose agricultural downtime coincides with the winter-road season – bringing out water trucks to flood the road.

It doesn’t take long for a surface layer of water to freeze, smoothing the road and building up its thickness. By late January the ice should be 70 centimetres (2 feet, 4 inches) at its thinnest, from put—in to take-out. Then, the road is declared open for light truckloads.

Making that call has become a science. If a load is too heavy or a vehicle drives too fast, it causes ice-deflection and water-motion, creating waves under the ice that can break through and crack the road. The feeling of driving on a solid substance belies the reality – ice floats on the water and bends easily under the weight of a truck. Though trucks aren’t allowed to travel the road alone, they must maintain 500 metres distance from each other in order not to compromise the integrity of the ice and cause a blowout. In some places, the speed limit is as low as 10 km/h (6mph).

Continue reading

All weekend I’ve been trying to write an article about oak trees for a rapidly approaching deadline, and not making much headway. I know what the problem is: Oaks aren’t a story, they’re too branched and sprawling, and I still need a path to follow through the woodland, or an acorn for distractable squirrel readers to nibble, or whatever. But I couldn’t find it, or maybe I just didn’t want to. Instead, I stared at a sprig of what I think is a blue or maybe a valley oak on my desk, and snuck outside to visit the trees in person.

Coffee in hand and cat on leash, I walked around the perimeter of our property, trying to better acquaint myself with the oak trees around my house. There are more oaks here than I’d realized: In addition to two massive trees that extend over our driveway, crowns touching, at least four saplings have sprung up nearby. The saplings are so dwarfed by their parents that I’d managed to ignore them. I walked down the road and noticed other oaks I’d overlooked, all different species: Some were small and shrubby, with spiny leaves, while others had lichen-spotted trunks and smooth leaves. I took pictures of all of them, hoping to identify them later, and let Calliope climb and sharpen her claws on their bark.

Continue reading