Most of us probably remember the first word we spoke in our native language.

Most of us probably remember the first word we spoke in our native language.

Mine was “Cat,” for I was fascinated by the ornery old Siamese that my parents kept when I was a baby. From there, I’m sure, I learned a child’s standard repertoire: “Mommy,” “Daddy,” “Doggie,” the colors red-yellow-green-blue, and those most basic early expressions of desire, “Love,” and “NO!”, and “I” and “Want.”

Most of us probably remember our first word in our native language, but I doubt many of us can remember a time when we knew so few words that we had to expand their definitions to cover an entire universe of necessary expression. When the word “Mom,” depending on how we said it, had to stand for everything from fear to hunger to whatever as-yet-inscrutable emotion was blowing through us.

I know I don’t remember. I work with words for a living. When I want to say, for example, that I’m cold, I have dizzying array of synonyms and phrases to call upon, each with different connotations and levels of extremity. I could be chilly or frigid, freezing or frosty, even glacial, hoary, icy, wintry, or just plain numb-lipped-club-footed-broken-fingered cold.

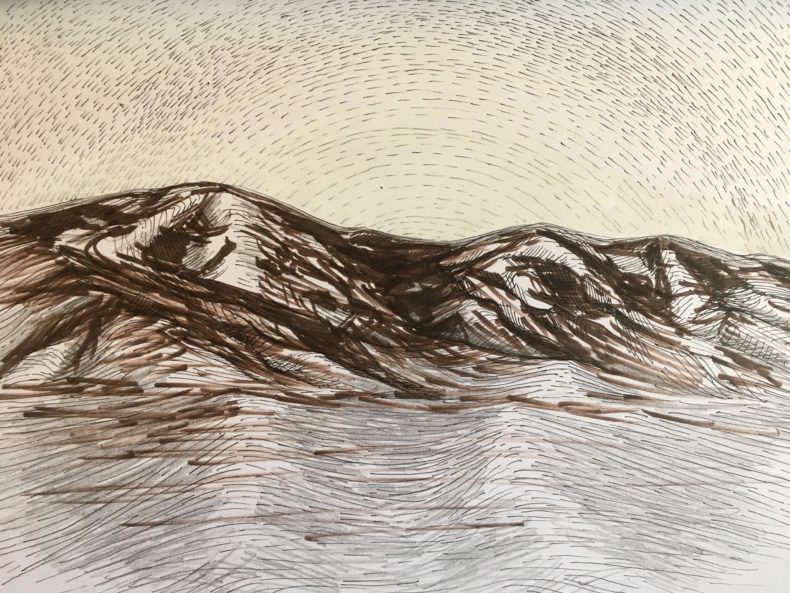

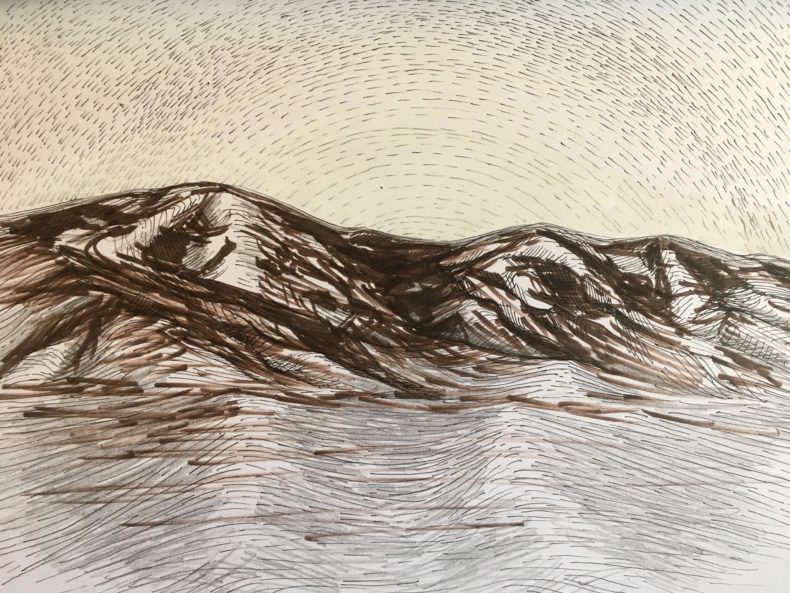

Then, I spent two weeks in Chile’s Atacama Desert this January. Only three of my five companions spoke English. When they talked among themselves, they spoke exclusively in Chilean Spanish, which, one of them—Fernando—gravely informed me, is even worse for outsiders than Argentine Spanish. I was awash in a sea of musical sounds whose meanings I could only grasp at based on context and hand gesture. Or from incessantly badgering the English speakers to help me out.

When Fernando grew tired of translating, he would turn to me and say drily, as if casting a spell, “By the end of this trip, you will be fluent in Spanish.” Continue reading →

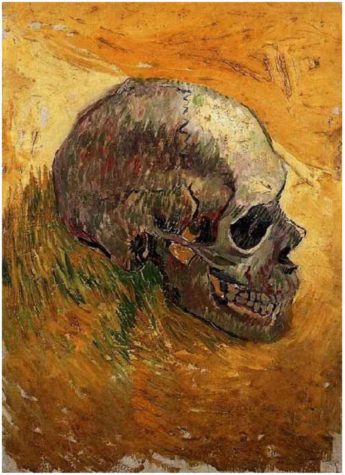

Within the last three years, two of my closer university friends have died. I moved away from Toronto a decade ago, and with those moves I was less frequently in touch with my college friends, but I always assumed we could go on picking up where we left off whenever I was in town. In attending their memorials and hearing more about their lives, I marvel at the changes they made since I lived nearby.

Within the last three years, two of my closer university friends have died. I moved away from Toronto a decade ago, and with those moves I was less frequently in touch with my college friends, but I always assumed we could go on picking up where we left off whenever I was in town. In attending their memorials and hearing more about their lives, I marvel at the changes they made since I lived nearby.

Most of us probably remember the first word we spoke in our native language.

Most of us probably remember the first word we spoke in our native language.

I am a man of science. Okay, perhaps not of science, but certainly near it. I’m science adjacent. But regardless, I consider myself to be bound, in the end, by logic and facts.

I am a man of science. Okay, perhaps not of science, but certainly near it. I’m science adjacent. But regardless, I consider myself to be bound, in the end, by logic and facts.