Next week, in the July issue of Scientific American, you can read a story I wrote about the fascinating archeological site of Teotihuacan. You may remember it as the Mexican site I wrote about in 2012 with an almost magical ability to draw in hippies. The story focuses on our growing understanding of the politics and culture of the city.

Next week, in the July issue of Scientific American, you can read a story I wrote about the fascinating archeological site of Teotihuacan. You may remember it as the Mexican site I wrote about in 2012 with an almost magical ability to draw in hippies. The story focuses on our growing understanding of the politics and culture of the city.

It’s a fascinating place for tourists and the most visited archeological site in North America. But it’s equally fascinating for researchers. That’s because, unlike the Maya to the east, Teotihuacanos didn’t have a proper written language.

“If I could go back in time, that’s the place I would want to go,” says Karl Taube, a well-known Mayan epigrapher (a fancy word for someone who deciphers ancient dead languages like Latin, Egyptian hieroglyphics, and html).

Let’s leave aside the fact that a tall, bearded white dude wandering around Teotihuacan in 200 AD would attract a fair bit of unwanted attention. Taube has puzzled over texts from across the Maya world – some of the most exciting archeological digs in recent history. Yet, if you gave him his choice of any period in history, he’d choose a place without any writing. Why would he do that?

Well, Taube is an epigrapher. Remember James Spader in Stargate? Sure you do, the nerdy guy who decoded the gate and was always clashing with Kurt Russell. He had the final showdown with that guy from The Crying Game. Taube’s like that, only he wouldn’t be caught dead in a show like The Practice.

Before I go on, this is not to be confused with iconography, like in Dan Brown’s books. Think of it this way: An epigrapher of the future would decode the King James Bible while an iconographer would run around trying to figure out why we put a lower case “t” on all our churches.

So epigraphers spend their lives looking at ancient carvings and trying to figure out what they say. This can be especially hard in Mesoamerica, because they had no connection to other writing systems in Europe. So none of the rules or logic from our texts apply.

Writing systems in North America started in 700 BC, long before the Maya or Teotihuacan, with the Olmec civilizations (named so by Europeans, who have a habit of renaming stuff that already have names).

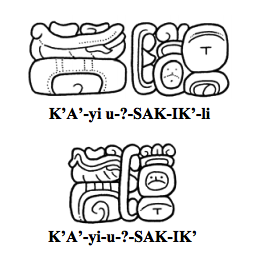

The Olmec system, however, wasn’t really “readable” in the modern sense. That fell to the Maya, whose glyphs could be read as both sounds and distinct things. In other words, Maya glyphs had the equivalent of that squiggly thing that Prince used for his name as well as the ability to spell out P-R-I-N-C-E. This, and other things, made it very hard to decipher. Once scientists did, they discovered a complex and rich language with grammar, vocabulary, and even a little room for personal style.

Take the glyphs to the right. The top one reads “he died” (literally, “it ended his pure breath”) and the second one says the same thing, except it refers to a woman. Notice the intricate relationship between the words and how they blend into each other. In the second one, the writer decided to squeeze them together just as we would turn “can not” into “cannot.”

Take the glyphs to the right. The top one reads “he died” (literally, “it ended his pure breath”) and the second one says the same thing, except it refers to a woman. Notice the intricate relationship between the words and how they blend into each other. In the second one, the writer decided to squeeze them together just as we would turn “can not” into “cannot.”

In fact, you could write out the Bible or Shades of Gray in Maya glyphs if you wanted. The same is not true for Teotihuacan. New evidence suggests that Teotihuacan may have actually conquered some big Maya cities and imported all manner of luxuries from around Mexico and Central America to their highland city. Yet writing was not one of them, despite the fact that Maya people had their own neighborhoods in Teotihuacan.

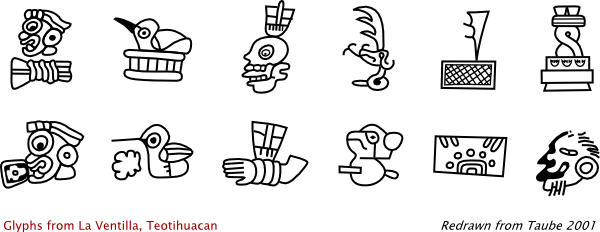

Or was it? Taube believes that Teotihuacan actually did have some kind of writing system. Not like the Maya, certainly, but something. Mostly he cites parts of dates, numbers, and a few proper nouns. There may have been more, but he just can’t be sure if they are truly words. Thus, we are left with a sort of philosophical question: When do cool little pictures become a written language?

In the “Plaza of Gyphs” at Teotihuacan, you can see a lineup (above) of various figures that look vaguely like ancient glyphs. Albeit simple ones. Or, you know, they could just be pretty pictures of cool stuff.

The Mexica (renamed “Aztec,” again by meddling Europeans) came hundreds of years after Teotihuacan fell and borrowed much from their culture (including their actual city). They similarly used writing for numbers and dates but not much more. The rest of their written language was a series of pictures that told stories but couldn’t really be applied to, say, modern bondage erotica (though, come to think of it…).

Believe it or not, our own alphabet started as a series of crappy drawings. “Z” is meant to be a sword and “K” is an open palm. The pictures in Chinese letters are easier to see, but you still have to use your imagination a little. The images at Teotihuacan – if they are words – are actually much easier to make out. So what are they?

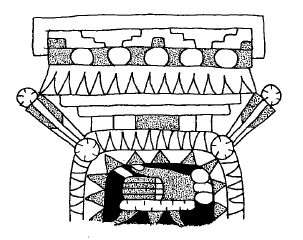

Here we turn back to Taube and archeologist Claudia Garcia-Des Lauriers. The figure to the left is from a piece of Teotihuacan pottery. Garcia-Des Lauriers points out that 800 years later, the Mexica would call it a tlacochcalco – an armory (literally a “house of darts”). So, is this the Teotihuacan word for an armory? Or is it just a drawing of one? Is there a difference?

Here we turn back to Taube and archeologist Claudia Garcia-Des Lauriers. The figure to the left is from a piece of Teotihuacan pottery. Garcia-Des Lauriers points out that 800 years later, the Mexica would call it a tlacochcalco – an armory (literally a “house of darts”). So, is this the Teotihuacan word for an armory? Or is it just a drawing of one? Is there a difference?

Furthermore, certain Maya sites show characters who look like they are from Teotihuacan carrying spears like these. We know that the Teotihuacanos conquered Maya sites. Was this a way for the Maya to describe them or was it a reference to a written word?

With the Maya glyphs, we had the advantage of lots and lots of examples, meaning we could see them start to repeat. Plus we had a few Spanish clergymen kind enough to buck the trend and not obliterate everything they saw and even try their hand at translating (using the complicated method of walking up to people and saying “hey, what does this mean?”).

But in Teotihuacan, as SciAm readers will see, the city collapsed long before the Spanish could document or destroy any of the culture. Time and decay did that for them. Leaving us to put the pieces together and guess.

Photo Credit: Shutterstock and Karl Taube.

One thought on “What’s in a Word?”

Comments are closed.