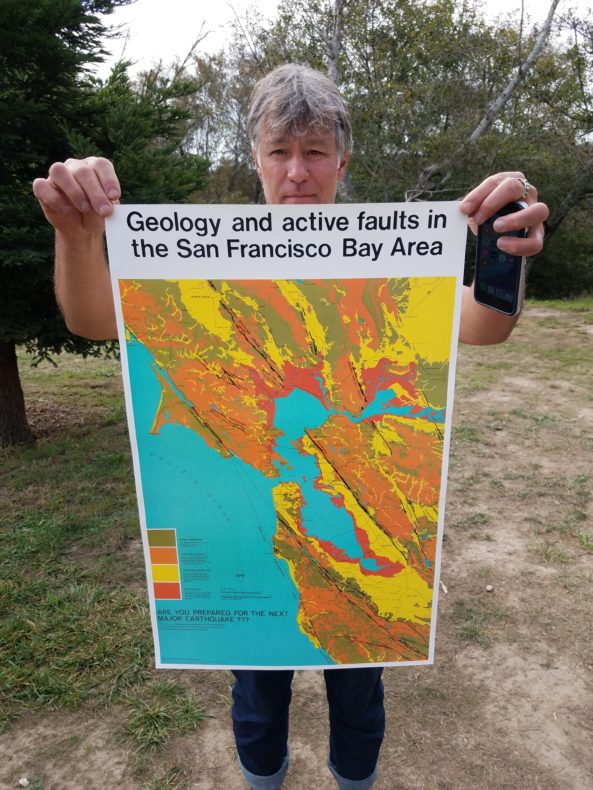

I walked along the beach a few days ago a quarter mile landward of the San Andreas fault zone. Surfers were swimming out and riding the curls back on the west side of San Francisco. Sets picked them up over the Pacific Plate and swept them onto North America. A hundred feet below, the fault lay buried under shifting sandbars and deeper layers of sediment, icing smoothed on day after day.

South of here stood the ragged projection of Mussel Rock, where the San Andreas fault continues from land into the sea, dipping under like a shark. To the north is the Marin Headlands where hills part, the fault making landfall again. An invisible boundary could be drawn between the two, passing through surfers lined up over the fault like iron filings to a magnet.

Things we take for granted, the earth moving under our feet, the heat down deep that drives the motion. This is why we are here. Without tectonics, this planet might not have life, at least not as we know it. By continuously supplying substrates and removing products, continental plates as they separate and collide create a geochemical cycle. Without tectonics to grind up mountain ranges, spitting volcanoes at the edges, there would be no crazy, colorful diversity from hummingbirds to the rainbows of minerals formed in oxygenated atmospheres.

The San Andreas fault, which runs from near Mexico to the sea just north of San Francisco, is the line between two of the larger global plates, which rub aggressively against each other, both heading the same general direction but at different speeds. For the last week I’d been paying homage to this fault by traveling with a friend along its trajectory where it passes through the Bay Area. Much of that course is by water, requiring the use of a craft. My friend, John, brought his sea-going dory for us to row the line. He called our journey ‘continental drifting,’ as if it were some new global sport and we were the only participants. Continue reading

I have what might best be classified as ‘manic costume joy.’ You’ve even heard about it

I have what might best be classified as ‘manic costume joy.’ You’ve even heard about it

On Sunday we sat outside on the sidewalk and carved our pumpkins. As we worked, we reminisced about past pumpkin carving sessions. My mom and my brother and I used to carve them on the kitchen floor, on the rectangle squares of linoleum. My husband and his sister used to carve their pumpkins in the living room on a protective barrier of newspapers. Both the houses we carved in are now gone, but the memory of the pumpkins links us to those places and those moments.

On Sunday we sat outside on the sidewalk and carved our pumpkins. As we worked, we reminisced about past pumpkin carving sessions. My mom and my brother and I used to carve them on the kitchen floor, on the rectangle squares of linoleum. My husband and his sister used to carve their pumpkins in the living room on a protective barrier of newspapers. Both the houses we carved in are now gone, but the memory of the pumpkins links us to those places and those moments.