Mom spreads maps over the dining room table. They’re oldish, not ancient, but the home I see in them is not the home I know. They are all of Colorado—mostly cities at the nexus of Rocky Mountains and High Plains, 40, 50, 60 years ago. The outpost of Ward, a funky old mining town up a sinuous dry canyon, guarded by two guys with broadswords. The hopping university town of Fort Collins, then just a smallish scatter of purple squares along a tidy grid of streets. And there’s Boulder in 1957, my hometown, where I’m visiting my family for the turn of the New Year.

We press the map folds flat with our fingers and lean closer. The city then was a tiny yolk at the core of its current footprint, pressed hard against the mountains. The mesa where my parents live formed its eastward boundary, a new neighborhood then, not yet swallowed and sprawled miles beyond with malls and business parks and subdivisions and natural gas wells, the fingers of the city and its neighbors creeping outward over the plains, grasping each other to form an amoeba of light and noise that pulses with traffic along a vasculature of roads. A place forever swallowing itself. Becoming new and new again, without becoming better.

Every time I come back, I grumble about how much things have changed since I was a kid. For all my sharp words, though, there’s something unchanging here. It rises in me when I see the rolling ponderosa-covered waves of the foothills breaking on the snowy, treeless slopes of the high Rockies to the west, when I see the plains reaching boundlessly east, haloed pink at the days’ two turns, from and towards darkness.

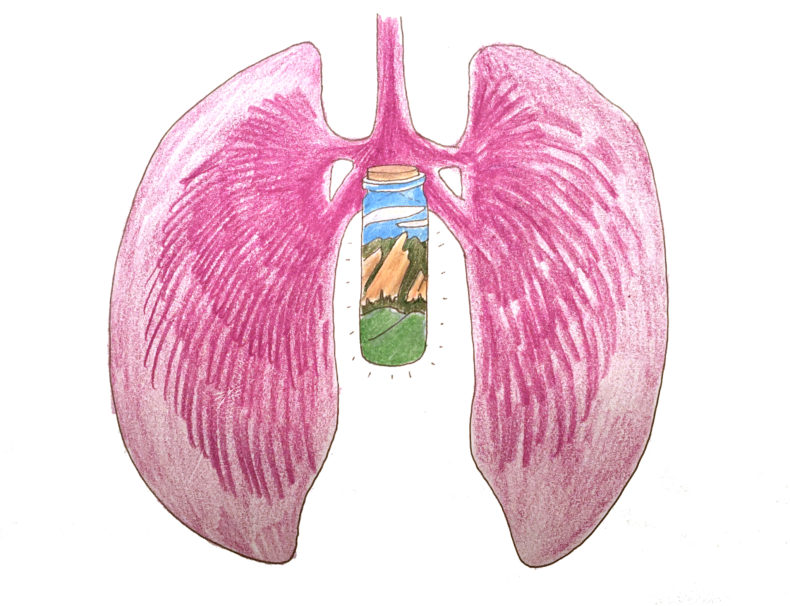

A bird, seeing its parents, learns its identity. Its shape. Its dance and song. The pathways it should migrate. Who and how it should love. This is like that—an imprint, but on the land where I was born, where I first learned the movement of light, the shapes of trees, the way yellowed grass, beneath a storm and slanting sun, becomes lit velvet. In a pigeon, magnetite in the beak is a compass to the Earth’s magnetic fields. Perhaps our bodies contain homing deposits of a kind too, oriented to something deep and indefinite, beyond conscious memory. I imagine my own as a tiny glass vial between my lungs, full of red dust and ponderosa bark and juniper berries and curling petals of moss campion and alpine forget-me-nots and meadowlark and hermit thrush song. A taste a smell a sound. A stirring unexpectedly awake.

It’s a small but substantial talisman I have learned to hold to. This past year, three friends died. This past year, I relearned how fragile is the machinery of my own body. This past year, so many friends have brought new lives into their own. Laying a hand over that spot on my chest—that homing place—I can touch a sense memory that reminds how some things remain steadfast, even as we careen always forward, awfully and beautifully, looking back at what was, looking ahead to the same-and-not-sameness of what is and will be.

The broad, jagged sandstone planes of the Flatirons—an ancient river delta broken skyward by the mountains’ uplift. The hard and sudden winds that stretch wings of cloud over the peaks, throwing garbage cans and picnic tables, snapping trees and power poles, howling around the house, drawing the world into older motion than the heartbeat of our cars back and forth on their diurnal schedules of 9-5, endlessly looping between home and work.

Leaving for the airport at the end of my visit, the Flatirons stand orange with sunrise, motionless despite the bus’s rushing speed. It’s a journey I’ve made dozens of times now. Seeing the lit stone, I think of another time, not so long ago, when the bus passed a coyote loping along the side of the road. She paused, unafraid, her head swiveling to mark our passage–so brief, and gone–before resuming her journey eastward.

This post originally appeared in January, 2020