When you’re exceedingly tiny, you can live almost anywhere – in an eyelash follicle, between grains of sand, or on an insect’s wing. You can probably find food and plenty of it, whether you prefer dead skin cells, blood, sap, or rotting vegetation. You can also get away with almost anything, like the male, deep sea-dwelling anglerfish Photocorynus spiniceps.

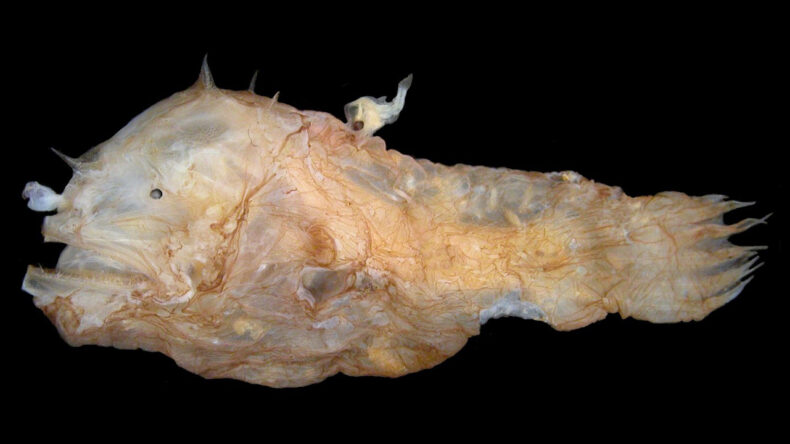

If you think the big ugly fish in this picture is male for some reason, look again. The big pinkish blob is the female. That little thing dangling off her back is not a sexual organ – it is the male. His quarter-inch-long body is made up pretty much exclusively of nostrils, to sniff out females, and testicles.

Only female anglerfish get a glowing dingle-bob to attract deep sea prey. Female anglerfish can live up to 30 years, and many never encounter a single male. When a male does happen to find a female, he bites her, latching on for life. His mouth dissolves, fusing into her body. The two fish become one – unless there are other males in the area, in which case up to nine anglerfish (eight males, one female) become a glowing, fecund hermaphrodite.

I’d forgotten about this horrifying-yet-transfixing mating ritual, which got some nice coverage by Katherine Wu in 2020, but rediscovered it while I was researching why some animals are so small. I wanted to know why this chameleon is so tiny, why this frog is so wee, and how there can be so many microscopic mites living all over our faces and in our eyelashes.

Most theories about why species grow or shrink come from islands, where isolated populations of animals often evolve larger or smaller bodies depending on the pressures they experience there – or cease to experience. At least among mammals, birds, and reptiles, larger species tend to get smaller on islands, and smaller ones get larger. But the pattern isn’t consistent across species, so is still controversial.

Animals can lose function in their organs, bones, and sensory systems as they get smaller. The world’s tiniest parasitic wasps, called fairy flies, have much simpler circulatory systems and fewer brain cells than their larger counterparts. In the case of anglerfish, the males are not only tiny, but have lost parts of their immune system, literally letting down their defenses.

The most interesting question, to me, is why miniaturization doesn’t always lead to simpler nervous systems or behavior. Miniature orb spiders don’t build less precise or complex webs than full grown ones. Tiny wasps behave a lot like bigger ones. One group of miniature, stingless wasp called fairy flies are devilishly good at finding other insects’ eggs. They lay their eggs directly underneath other insects’ larvae, so that when their own eggs hatch, those newborn larvae crawl out and eat the other insect’s babies. Scientists recently discovered a new species of fairy fly, which they named, of all things, Tinkerbell nana.

As relatively large land mammals, we have flexible minds, strong bones and sophisticated tools. Still, I’m floored by this video of a miniature featherwing beetle, her bristled wings move in a unique, swooping figure eight through the air. The flight looks goofy in slow motion, but the fan-like wings work beautifully, propelling her through the air as fast as insects three times her size. Maybe this featherwing beetle, no bigger then a single-celled amoeba, will reveal new ways to fly.