A snake oil salesman and some hedge funds partner up to pimp the latest ‘synthetic biology’ scam—as phantom revenue, a hocus-pocus business model, rampant related-party games, and a decade of colossal failure get shoveled into yet another garbage SPAC. Ginkgo Bioworks is a colossal scam, a Frankenstein mash-up of the worst frauds of the last 20 years.

So begins a 2021 short-seller’s report, representative in style of the literary form.

This year I’ve been reading a fair number of ‘short reports’, a type of inflammatory, investigative presentation aimed at convincing other investors to dump a stock. Short sellers play an important ecological role in the public markets, clearing away excess valuations that otherwise build into bubbles. If one couldn’t sell short, investors could only speculate in one direction—upward. But like all scavengers, activist short sellers are roundly loathed.

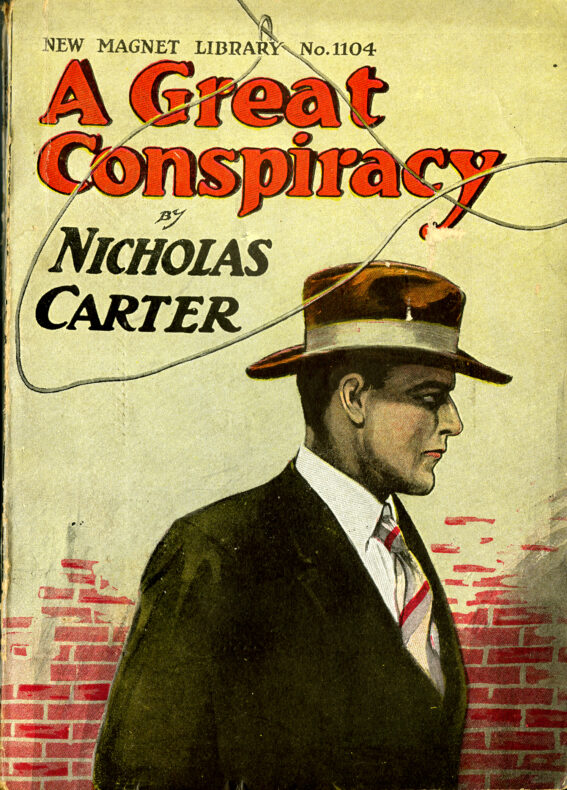

The short reports I’ve been reading have done nothing to dispel this grimy reputation. There is a kind of disdain for their victim, a schadenfreude in the suggestion that they will not only bring down a company but gain from its downfall, too. But there is something else in the literary style. Each time, I sense I should be wearing a fedora. The language is so reminiscent of noir detective fiction that my surroundings transmogriphy into a dimly-lit bar, a lone saxophone playing at the edges while, as I read, my inner voice takes on a transatlantic accent.

At first it was just jarring; most writing by financiers is cold and formulaic, not to mention generally bad. But the detective fiction influence clicked into place when I realized the author was casting himself as a hard-boiled private eye who could ‘smell a rat’ a mile away and separate the ‘crooks’ from the ‘crackerjack analysts’. If he was hated it was merely because he was mysterious and misunderstood, and he could see crimes in the markets that others couldn’t.

Much has been made of the influence of science fiction on subsequent technological development, and life imitates fiction in other genres, like the noir example above. Doug Rushkoff’s new book Survival of the Richest: Escape Fantasies of the Tech Billionaires argues, in part, that the narrative structure of Western storytelling contributes to our pathetic response to 21st century problems. The futuristic visions of our current day are designed to present a world where a chosen few survive the apocalypse—and conveniently find a way to eliminate the working poor from view.

His Timothy Leary-aligned, communitarian analysis of our current predicament suggests that formulaic story arcs, which propel the protagonist forward through the hero’s journey, have formed our attitudes toward climate change and other global catastrophes. In his view, the Bezos’s of the world have taken the rising action toward crisis as a literal cue to follow the parabola to escape velocity and take it all into space.

Literature has made its mark on the human mind in all sorts of ways, but in this particular mess, I see more danger in one concept borne of video games: the NPC (non-player character). Most of the people you see in triple-A games are not real people. This encourages a solipsistic view of the world where most people are disposable, and I’m beginning to think the most nefarious effects are not the usual targets of hysteria: the school shootings or the Incel movements. They’re seen in a model of the world in which only, maybe, a few thousand people on Earth are worth knowing. The rest are NPCs.

If Web3 comes to fruition in the way that some imagine, there is a very slight possibility that its contribution may be this. The realization that our world is, and should be, multiplayer.