Last September, a tiny, itchy welt appeared just above my left hip. I thought I had an insect bite. I was visiting New York City at the time, and I worried it might be a sign of bed bugs.

Last September, a tiny, itchy welt appeared just above my left hip. I thought I had an insect bite. I was visiting New York City at the time, and I worried it might be a sign of bed bugs.

But after I flew home, the welt began to swell. Soon it was big as a blueberry. But rather than being blue, the lump turned scarlet. Because I am the type of person who can’t leave well enough alone, I tried to pop it. That just made the lump angry. It began to ache.

This is bad, I thought. This is not good at all. I worried that my bite had become infected. I thought about trying to lance the lump with a sterile needle. But what if I had necrotizing fasciitis, a disease caused by flesh-eating bacteria. I googled ‘necrotizing fasciitis.’ (Do not google necrotizing fasciitis.) I snapped a picture of my lump and sent it to a friend who also dabbles in self-diagnosis. She told me a story about a friend of a friend whose brother was bitten by a poisonous brown recluse spider in Brooklyn and developed necrotizing fasciitis. I googled ‘brown recluse spider necrotizing fasciitis’. (Do not google this either.) When the throbbing lump reached the size of a plump grape, I went to the doctor.

Dr. Karen congratulated me for coming in, and sliced the lump open with a scalpel. “Purulent” was the term she used, which means full of pus. And indeed it was. She dipped a swab into the incision, and hustled it off to the lab to be cultured. “To see if it’s MRSA?” I asked. “Exactly,” she said. I had been joking. She was not.

The results came in three days later: “Light Staphylococcus aureus – Methicillin Resistant (MRSA)”

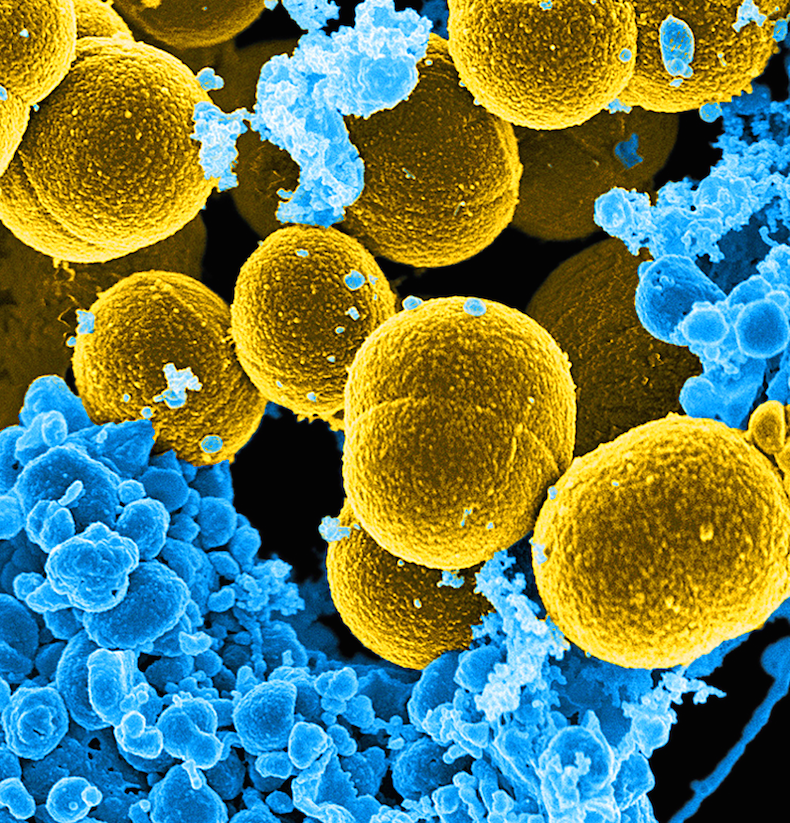

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, or MRSA*, is a fancy name for staph that has picked up resistance to a many common antibiotics. These bacteria are not typically troublemakers. “Staph is largely a commensal,” says Robert Daum, a physician at the University of Chicago who studies MRSA. “It’s part of our flora.” And MRSA doesn’t have to be dangerous either. But some strains are.

I didn’t know much about MRSA, but what I did know led me to believe it’s an infection — a terrible, life-threatening infection — that you pick up in hospitals. And it can be, but that’s only part of the story.

About two decades ago, MRSA infections began cropping up outside of healthcare facilities. At first researchers suspected that these infections had been brought into the community by former patients. But they soon realized they were looking at new, genetically distinct strains. And those strains begin to spread and infect even young, healthy people.

By 2012, the country was in the midst of a MRSA epidemic. Daum had hired two nurses to help him recruit patients for a study he was conducting. “They were down in the emergency room running from one patient to the next because patients were coming in so frequently with skin and soft tissue infections,” he says.

Treating MRSA skin infections is relatively straightforward. Most simply need to be opened up and drained. My wound healed quickly. But just because the infection is gone doesn’t necessarily mean I’m free of MRSA. Staph likes to take up residence on the body, a process called colonization. “Most people believe that if you get an infection that you’ve been colonized first,” Daum says. But colonization can be difficult to prove.

A month after my infection, I had Dr. Karen take a nasal swab, which came back negative for MRSA. But Daum points out that’s not enough. “We now know that the nose is not the primary place where you’re colonized,” he says. Daum adds that you also have to look at the throat and the groin.

And if I am colonized, it may or may not be problematic. Perhaps I’ll get another skin infection. The recurrence rate of MRSA skin infections is high. But it’s also possible I’ll never have another one. Researchers don’t yet understand what factors contribute to recurrence.

The uncertainty is frustrating. Should I be worried about myself? Should I be worried about my family? My daughter had a bump that looked suspiciously similar to mine. And when I sat her on my hip, our wounds lined up perfectly. But her lump never amounted to much, and there was no way to culture its contents.

Even if my family discovered that we’re all colonized with MRSA, it’s not clear what we should do about it. You can find all kinds of laborious decolonization protocols involving bleach baths and special soaps online, but decolonization is “fraught with problems and generally doesn’t work,” Daum says.

So all I can do is wait, and hope that if I get another MRSA infection, it’s as mild and treatable as the last one.

***

*Fun fact: Physicians don’t prescribe methicillin these days, but we still call it MRSA. Another fun fact: I’ve been pronouncing it “Mersa,” which sounds like someone’s great aunt, but at least one of the researchers I interviewed spelled it out — M.R.S.A.

Image credit: Frank DeLeo, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID)