Corvids are a wonderful genre of beast.

I was reminded of this fact not long ago when, biking back home across southeast Portland from the waterfront, a veritable river of crows began streaming overhead. Thousands of them blurred and bobbed and circled each other in a stuttering current from east to west. This current eddied over warehouses. Spilled over parking lots. Formed a recirculation hole over the freeway, then fanned into a delta and out of sight beyond the skyscrapers of downtown. Corvid biologist John Marzluff later told me that the crows were likely heading for a communal roost to settle for the night. There’s one in his home city of Seattle that’s 15,000 strong.

Besides coalescing into this sort of breathtaking “murdermuration,” as I’ve decided to call it, crows recognize their dead, understand analogies, and one species, the New Caledonian crow, even makes its own tools.

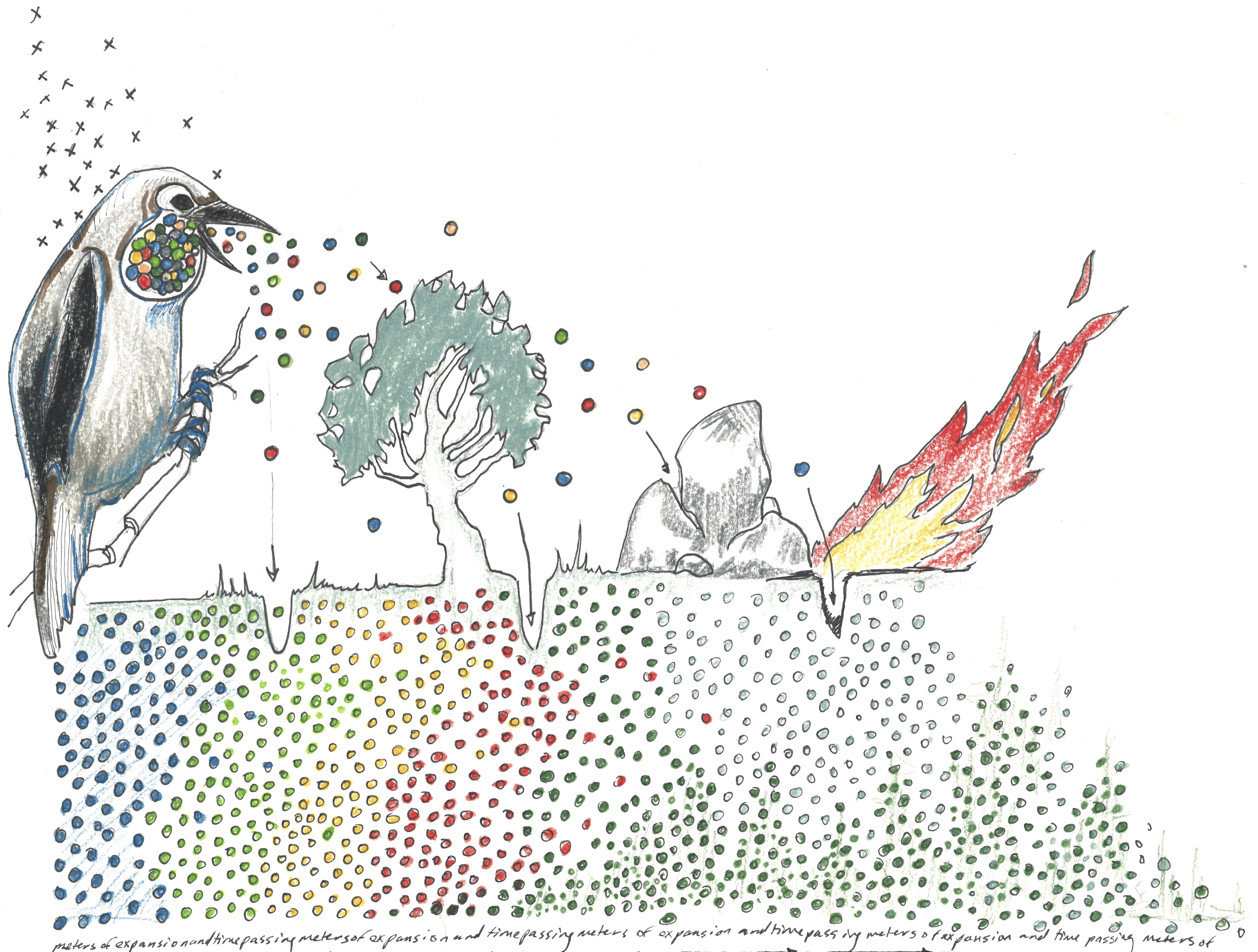

Yet while crows and ravens get most of the attention, smaller members of the corvid family like jays and nutcrackers are out in the world busily building and rebuilding forests. Not on purpose, of course, but through a behavior charmingly called “scatter hoarding,” which basically involves stashing seeds around in various places for later devourment. (The same phrase could easily describe the way I distribute books throughout my house.)

In February, a group of scientists led by Mario Pesendorfer of University of Nebraska, Lincoln published a sweeping review of the available research that elegantly lays out just how important and pervasive this relationship is: Many broadleaf trees, including hickories, oaks, chestnuts and beeches, rely entirely on scatter-hoarders to spread their large, heavy seeds, while 20 percent of pine species do. The authors suggest that this reliance may help some of these species better weather forest fragmentation caused by human activities like farming, or shift their range in the face of climate change.

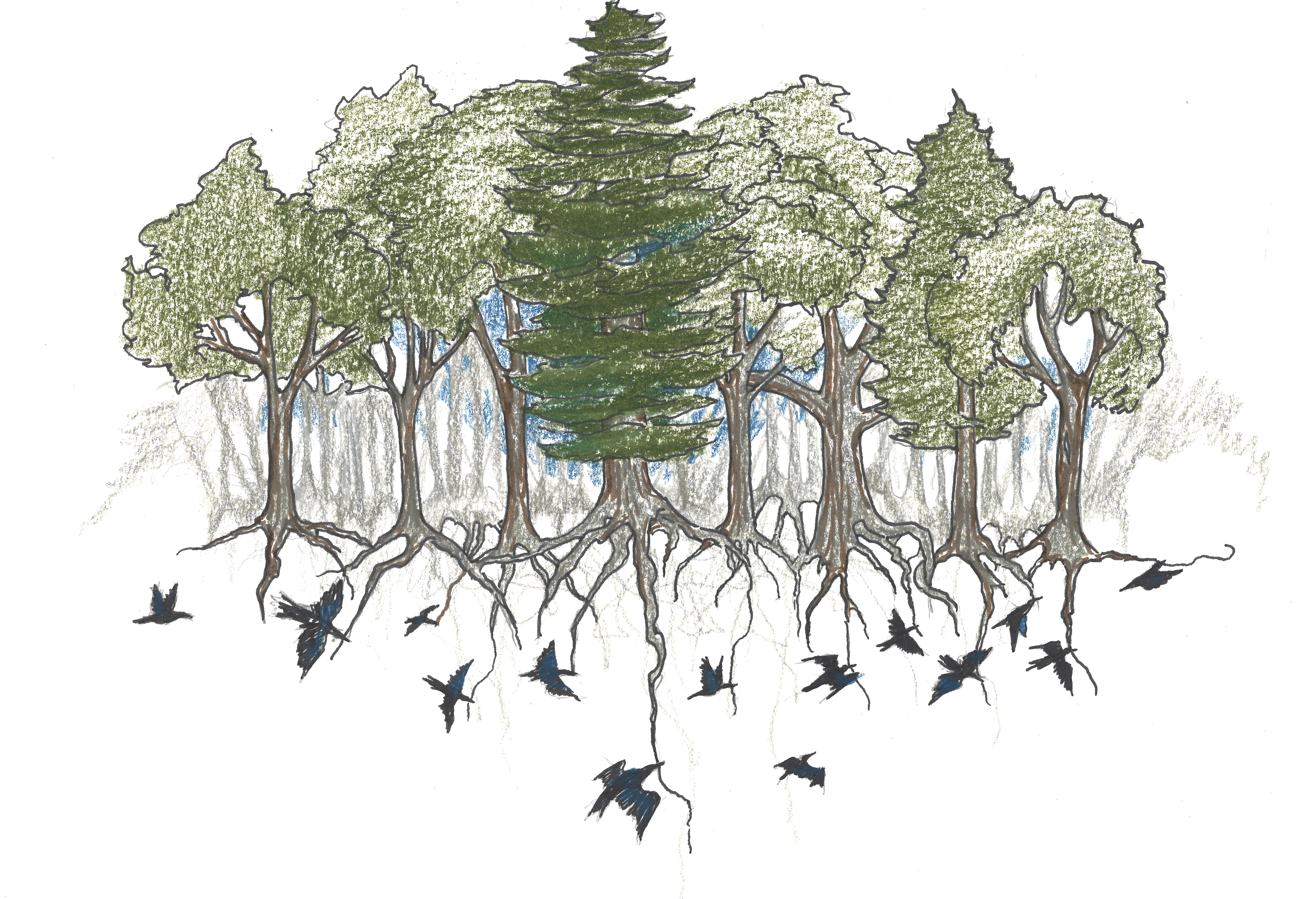

Unable to walk or fly themselves, in other words, these trees borrow the wings of birds.

It works like this: Even though scatter-hoarding corvids tend to have “formidable spatial memories,” the authors write – noting each location with a treasure map X-like precision – they rarely recover all that they’ve stashed. Sometimes they forget. Sometimes they die. Often they stash far more than they could realistically eat. Nutcrackers can carry up to 150 pine seeds at a time in a handy expanding throat cubby called a sublingual pouch, and regularly cache over 500 per day – rounding out to tens of thousands per season and double the amount they actually need.

Not only do corvids move lots of seeds, some species favor the most viable seeds – improving trees’ chances of taking root. Even though just 11 percent of American beech seeds are viable, for example, these are the only ones that blue jays will collect and store. Corvids also move seeds long distances, from hundreds of meters to dozens of kilometers. And while some birds may pop a seed in a rock crevice or some tree bark where it’s unlikely to take hold, many actually prefer stashing them in the same habitats their source trees favor. Jays hide seeds in the shade of other plants, where soil is moister and gnawing herbivores can’t reach – improving seedling success. They also tuck seeds away in freshly disturbed environments, like burns and the edges of cleared fields – setting into motion the forest’s slow but insistent revolt against newly-opened space.

So it is that North American beech and oak rapidly expanded their range northward in the wake of retreating glaciers after the last Ice Age. Likely with corvids’ help, they moved at speeds that, for trees, could be considered a sprint: Hundreds of meters per year.

None of this is new, really. As the authors note, poets heralded corvids’ forest-seeding tendencies as early as 1653, and foresters in Europe have long noted their utility. But now, some are actively supporting corvids as a way to bring declining forests back. In Spain, managers plant islands of seed trees to attract scatter hoarders and enlist them in restoring oak woodlands. On California’s Channel Islands, scientists have studied the possibility of restoring the endemic Island Scrub Jay to assist with the restoration of oak and pine after the removal of livestock.

In an era where our profligate fossil fuel burning is tipping ecosystems into chaos, perhaps we can find new hope in old systems of resilience.

Original artwork by the author.

Dear Sarah, what a lovely article!! Thank you so much for your interest in our work! Would you mind if I used your artwork in oral presentations? It’s lovely!

Cheers, Mario

Wonderful information. But, how do they know which Beech seeds are viable???

Great article Sarah and I LOVE LOVE LOVE the artwork! ❤️❤️❤️‼️

So interesting, pics are a super sweet touch.

Thank you!

Insightful and a reminder, once again, that we are all interconnected! Thanks and I love your art, too.

I’m enamored with all birds but the jays sometimes take a back seat in my affections, because of their “bossy” habits. I’ll look on them more tenderly and with greater gratitude, from now on. Lovely artwork, Sarah.

Wonderful article! Another collective noun for a group of crows that I love is a storytelling of crows! If you ever want to see where they are flocking to, it’s the bus mall downtown and the commons on the PSU campus. They look amazing in the trees and they have a LOT to say about it.

Sy–I am SO there. Those crows and I are going to have a long and satisfying and mostly unintelligible conversation.