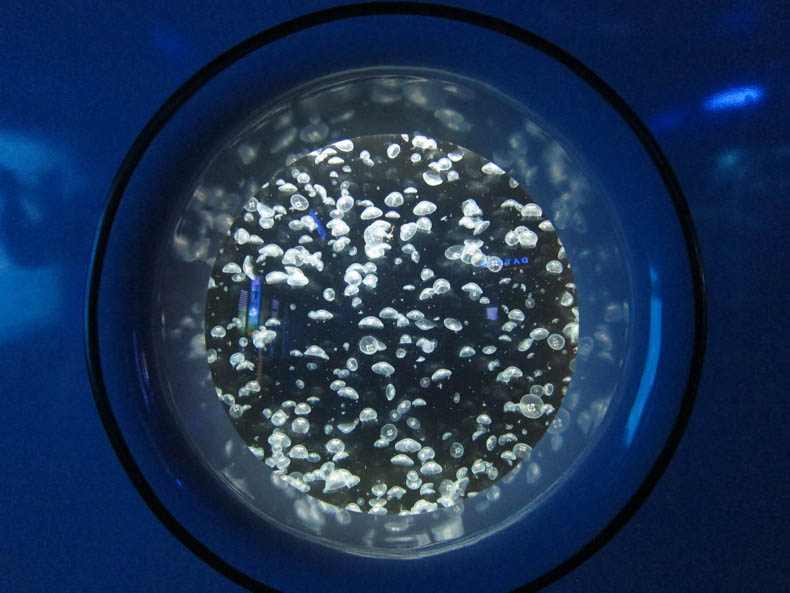

In a dark gallery alongside Baltimore’s Inner Harbor, a horde of glowy, gelatinous bulbs are drifting. A living lava lamp, someone calls them, and that’s what they are – jellyfish, mesmerizingly lit for the benefit of visitors to the National Aquarium in Baltimore.

In a dark gallery alongside Baltimore’s Inner Harbor, a horde of glowy, gelatinous bulbs are drifting. A living lava lamp, someone calls them, and that’s what they are – jellyfish, mesmerizingly lit for the benefit of visitors to the National Aquarium in Baltimore.

Aquariums have been keeping jellies for years. I first saw them at the Monterey Bay Aquarium in about 1994, when I visited a friend in the San Francisco Bay area and we took a day-long pilgrimage. I couldn’t believe the terrifying, painful creatures of childhood visits to the seashore were so shockingly, glowingly beautiful.

Jellyfish went on display at the aquarium in Baltimore in 2008 or so. They range from the northern sea nettle, with its lethal-looking tentacles, to the placid-looking moon jellies. Maybe it’s just the onomatopoeic name, but they make me think of cows – moooooooo, they might say, if jellies could talk, swirling around their tank.

Of course, jellies can’t talk. They’re not much beyond a stomach and reproductive organs. The ones with the classic dangly arms have the painful tentacles on the outside, laden with the stinging cells called nematocysts that shoot tiny harpoons at their prey. In the middle are the oral arms, long frilly appendages that draw the food up to the mouth.

When I visited the jellyfish last Saturday the blue blubber jellies were swimming in their breakfast of newly-hatched brine shrimp, like tiny golden flecks in the water. The aquarium offered a special tour before opening hours to a group from the D.C. Science Writers Association. This is the sort of thing that happens when you’re a science writer: people show you science.

Which meant we also got to visit the room where the jellyfish hang out before they go on display. In that concrete lab, a short walk from the harbor’s edge, mood lighting is less important, and it’s much easier to see how the jellies are kept.

Water in aquarium tanks is constantly cycled through a filtration system, with a screen to keep critters from getting sucked in. But, for a jellyfish, a screen is a calamity. They’re kept in round or oval tanks with a circular current that pushes them past the screen at an angle; while water leaves to be cleaned, the jellies flow on, their parts intact.

Keeping jellyfish is not, we learned, for the faint of heart. Jelly husbandry professionals can learn more about taking care of them at Jelly School, a two-day program being offered in March 2015 at the Monterey Bay Aquarium. Non-professionals probably shouldn’t bother trying. There’s the special tank. The live food. And, periodically, the National Aquarium’s general curator told us, you have to take all the jellyfish out and bleach the tank to kill the pesky little hydroids that hitchhike in, sting the jellies, and steal their food.

And, even with professionals taking all the precautions, I got the sense that jellyfish are still difficult creatures. In one of the tanks in the lab, a lone moon jelly was sucked bell-first against a screen. It waved its tentacles. Its compatriots pulsed on by.

photo and video: Helen Fields

Fascinating! Never thought about the difficulties of keeping jellies.

But having just learned something else about jellies a month or so ago, I take issue with this sentence: “They’re not much beyond a stomach and reproductive organs.” Check out this neat feature by Susan Milius:

https://www.sciencenews.org/article/seeing-past-jellyfish-sting