I’ve been thinking a lot about resilience lately, that ineffable quality of being able to withstand trickling insults and outright catastrophe. It characterizes the Japanese ability to remain civil and calm throughout their ongoing weeks of dread, and the ability of some natural systems to bounce back after even the most egregious of impacts.

I’ve been thinking a lot about resilience lately, that ineffable quality of being able to withstand trickling insults and outright catastrophe. It characterizes the Japanese ability to remain civil and calm throughout their ongoing weeks of dread, and the ability of some natural systems to bounce back after even the most egregious of impacts.

It also describes the ability of a healthy adult to resist disease or injury, when infants, the elderly or the infirm might succumb.

Resilience, in other words, is wonderful stuff if you can get it.

So what then to make of a pathogen—Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the tuberculosis agent—that is resilient enough to persist a century or more under unfavorable conditions, only to spread again, and rapidly, with devastating effect when conditions are in its favor once again?

Researchers at Stanford and several Canadian institutions published new evidence in PNAS this week that tuberculosis can do exactly this. Using samples collected as part of ongoing TB monitoring and treatment programs in Canada, they found genetic evidence that the tuberculosis that devastated the people of the Canadian northwest (today primarily the provinces of Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta) in the late 19th and early 20th centuries had entered the population a hundred years or more before making itself tragically well known.

Pathogens, like any living organism, are constantly evolving, accumulating changes in their DNA. Just like families, or breeds of dogs and cats, they form lineages over time. And those lineages can be tracked through the changes in DNA content and sequence that define them.

What is more surprising is that when it comes to pathogens, which live in very close association with their hosts, those lineages can in turn be used to trace the twists and turns of human affairs through time.

In this case, Caitlin Pepperell, an infectious disease specialist and medical researcher at Stanford who is interested in how epidemics work, had been studying historical and contemporary TB epidemics among aboriginal populations in Saskatchewan. Then, a colleague sent her DNA “fingerprints” from TB strains from remote aboriginal communities in Ontario, and they “looked suspiciously like the ones I had been studying for so many years,” as Pepperell kindly noted in a gentle correction to the first published version of this story. How could that be, she wondered, when there was vanishingly little contact between the two populations?

The answer, as it so often is, was history. And in Canada, history means one thing: the fur trade.

Pepperell set out to gather TB samples from Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba and Alberta to complement those from Saskatchewan, and to test her hunch that the most prevalent strain of TB in the northwest, identified as DS6Quebec, was carried there from Quebec by fur traders and voyageurs long before the deadly epidemics set in.

As early as 1710, European voyageurs and traders were traveling deep into the Canadian interior, often staying for years at a time, establishing close ties with First Nations communities, and settling down in a kind of temporary, fungible matrimony known as country marriage. These first European visitors to the Canadian northwest brought with them many things, including, the new research shows, the DS6Quebec strain of tuberculosis.

The traditional view had been that TB was first introduced to the west with the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway in the 1870s, and the establishment of Indian reservations starting at about the same time. That, certainly, was when the first severely lethal outbreaks occurred. But the new analysis indicates that the infective agent was there all along, surviving at low levels despite conditions unfavorable to its spread: Resilience in microscopic form.

And for those 100 years, in relative isolation, the people of the northwest lived on regardless: Resilience in human form.

What was going on while the tuberculosis slept? First, other introduced diseases, including smallpox, took a devastating toll. Then the fur trade dropped off, and trading routes shifted. New people moved into the territory—some of them aboriginal groups pushed west by settlement in eastern Canada, or north by the wars of extermination in the American west; and some of them Métis, the indigenous Canadian people descended from aboriginal and European ancestry.

Then came the railroad, the reservations and the great slaughter of the bison—and with them deprivation and genocidal poverty for the natives and the Métis.

And then, finally, tuberculosis. It was only once the human resilience was severely undermined by other forces that the microbes finally started to win out.

To those hanged, hounded and hungered in the interests of settling the Canadian west, teasing out the details of disease spread would surely seem a small thing. But the unexpected story of TB’s early spread, and its long ghostly residence in their communities, hints at a far deeper tale.

Julie Granka, the second primary author of the new study, happens to be in a class I teach at Stanford. (Imagine my surprise when I recognized her name on the authors list: the world has become very small indeed.) Her main research motivation, she says, is “to study historical events in a rather indirect way—by studying genetic data. I was really interested in the potential of studying M. tuberculosis genetic data to learn more about and to support what we knew [about] human populations during that period.” She studied the bacteria, in other words, to learn about the people.

The Métis have been called “the forgotten people.” That term could certainly extend to cover all those, mostly aboriginal, people claimed by TB and other infectious diseases during the cruel decades spanning the turn of the 20th century. In a small, but very tangible way, uncovering the traces of their history in the genetic makeup of tuberculosis keeps at least this part of their story alive, and unforgotten: resilience in narrative form.

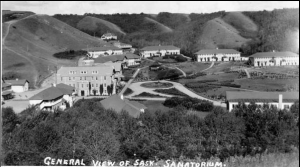

**Credits Top: Canoes in a Fog, Frances Anne Hopkins, 1869. Glenbow Museum, Calgary, Alberta. Fort San, Stony Rapids: Saskatchewan Archives Board. Batoche: Jordon Cooper/flickr. Special thanks to Dr. Stephen Sanche of the University of Saskatchewan College of Medicine.

good story, well told. it reminds me of the prevailing narrative about the emergence of hiv into the human population and its subsequent spread. and other pathogens, e.g., nipah virus. a lot has been written about plague in this respect. does it also follow this pattern?