My aunt is standing in front of the book shelf scrutinizing two rows of photos. It’s 1 a.m., and a little while ago I was dead asleep. But now here I am, awake, because here she is, standing in her pajamas with her hands pressed into her back, looking hard at faces in the frames. Again.

I read recently that disrupted circadian rhythms, affecting glial cells in the brain called astroctyes, may cause neuroinflammation and hasten the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. I wonder if that’s true in the case of my aunt’s dementia. I decide that it is. Her sleep patterns have been off kilter for a while, but since the fire she is up at all hours many nights. I know this from tonight’s experience and also because she periodically calls or sends a blank text in the wee hours, or unknowingly shoots and sends a photo of, say, the floor, or her chin, around 2 a.m. Apparently, I’m not the only recipient; my cousins tell of similar late-night communiques.

California’s latest fires have been devastating, but for my family it was the 2017 flames that changed everything. That’s when my cousin lost her beautiful house with the mountain view. That’s when her 84-year-old mother (my aunt), who had been awakened by alarms and evacuated in her bathrobe from her retirement community, lost her mind.

Well, not all at once, of course. Cognitive decline (often memory loss) typically happens over years; the elderly brain often struggles even without the underlying brain pathology and overt manifestations of dementia. Mostly, in my aunt, that struggle had manifested in harmless enough ways, as conversations moving in ever-tightening circles, as stories repeated ad nauseam.

Then the fire came, terrifyingly fast, hot, and close; you could taste the flames. And suddenly, she was ripped from her home—one building on the property was burning when she left–and living “in some man’s house” until the danger passed. Suddenly, she couldn’t remember that the person who took her in was her son. It seemed the frightening experience pushed her brain into a new dark place.

More than a year later she remains confused about her relationship to her youngest son, his relationship to his wife, and most other matters. And after finally moving back to her truly lovely apartment in the retirement community, she now hates it there. She had no friends, she says. People there steal from her, she insists. The food is inedible. Her daughter is mean to her. One granddaughter takes advantage of her. Another is kept from her. In her rattled mind it seems the lies told and wrongs done to her–though exaggerated or simply untrue–explain everything. They permit the madness.

When not present I become part of the unfortunate story she’s written, despite our special bond. (She has long called me her “other child.” She listened to me cry over the phone when my mother was dying, somehow making me laugh at the hideousness. She used to post hilariously over-the-top praise for my posts on this site. She was, after my mom, my biggest fan.)

Now, when I’m absent, I’m “that sneaky girl” who has taken something from her or owes her something; I’m someone she doesn’t want to see. Whatever shaped it—a twist on a memory, a flip comment misunderstood–a nugget of distrust is caught in her mind with my name on it. It’s terribly sad.

Since the upheaval she seems to have lost her empathy for others. The biggest tragedy of my cousin’s burned-down house, in her mind, isn’t the destruction of my cousin’s life and possessions, but the loss of my aunt’s many sculptures that had been in the house. “All of my art was destroyed,” she recalls when asked about the fire. That her daughter’s life was turned to ash doesn’t come to mind. Her mind has folded tightly inward.

My cousin says, “I’ll probably always see this time as when I lost my mother.”

Scientists say that emotionally charged experiences can exacerbate the symptoms of dementia (whether Alzheimer’s or other kinds, which differ in their pathology and symptoms). What exactly leads to a particular personality change isn’t known, but the already impaired brain clearly buckles under extra pressure.

I talked about it with Dr. Deborah Blacker, a geriatric psychiatrist and epidemiologist at Mass General and professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. It may seem that a switch was flipped by the trauma of the fire, turning my aunt’s memory off and distrust and unhappiness on, but it’s not quite that clear cut, she says. When something dramatic happens, “a cognitively impaired person simply has less reserve to deal with it. It becomes one more thing to try to sort out on top of so many other confusing things.” If someone’s memory is already weak, “then a trauma may be fresh each time, something you find out over and over,” Blacker says. “That becomes its own kind of pain.”

I suspect such pain can foster excess negativity, especially in someone who already saw life through a gray lens—as my aunt certainly has for many years.

More generally, there’s a connect-the-dots quality to life, Dr. Blacker says, and as we naturally miss a lot of details, we have to fill in the blanks. Our brains, normally, do that pretty well. “But as cognition is impaired, a person misses more and becomes less good at figuring out what’s missing. It gets harder to play the game of connect the dots when you’re short on dots.” Everyone meets trauma where they are, she says. “If you have poor emotional coping mechanisms already, you’ll struggle more to adapt to emotional things.”

With Alzheimer’s, the damage to the hippocampus tends to hit short-term memory first, and hard. Paranoia is also super common, Blacker told me, as a way of trying to make sense of a world that no longer has defined edges, perhaps a way of expressing loss and assigning blame for that loss. For my aunt there’s an almost obsessive focus on what’s missing—often jewelry—with an assumption of foul play. Her memory of having the item may be decades old, but she believes it is current. And she doesn’t have the tools to work through the possibilities. So, her brain nabs the simplest answer it can find: Someone took it. Similarly, she doesn’t remember the recent visits from her family, so, simply, they must not have happened. In fact, her family never comes to see her anymore. In fact, there is a deliberate effort to keep certain visitors from her. It seems the more her world constricts, the lonelier she feels, and the more tragic her created narrative becomes.

While some kinds of dementia bring about total flip-flops in personality, whether turning a gregarious person inward or stripping a shy person of inhibition, in my aunt’s case it’s more an enhancing of traits she already had. As mentioned, clouds have always fogged her view of the world. With love I can say she’s reveled in sharing her many disappointments. So, already leaning toward feeling slighted, her addled brain now fills in the blanks with extreme stories of dishonesty and abandonment, mostly by family. It is family, after all, that she relies on most; we are the people who still populate her shrinking world, and we are the ones best positioned to disappoint her.

When she’s told I’m on my way to visit for a few days, she gets confused about who I am and tells her daughter that I shouldn’t come. It’s her damaged cortex talking, I remind myself as I recall our lovely visits of the past…when she begged me to stay longer.

Once she sees me, she is my loving aunt again, to some degree. The visual is a powerful reminder. But she whines to me about others who aren’t there, especially her kids, who are horrible and mean and don’t care that she’s miserable. I envision the plaques–those abnormal clusters of protein fragments built up between nerve cells—eating away at loving thoughts, replacing them with ugly ones.

Then, over and over, as if reading from a script, she fingers the various people who are stealing from her. I promise to look into her accusations; inwardly, I blame the tangles, the twisted strands of proteins in her dead and dying nerve cells that can block the passage of nutrients. And logic. And good will toward her fellow humans.

Cells are dying. The brain is shrinking.

I know this, yet my inevitable crossing to the other side of her confusion and distrust will still be painful.

Almost 2 a.m. now. She shuffles around picking up papers and pictures, putting them down. She examines the same item more than once, each time as if anew. If it weren’t someone I love, it would be fascinating to observe.

Cells are dying. The brain is shrinking. I’m trying to be grateful she still knows me in person, saving the ugly comments (about me, at least) for when I’m gone. There’s still much love here. She’ll cry when I go and make me promise to return soon. She’ll continue calling me after midnight, maybe a little bit on purpose. But next time I’m in town she’ll have to be coaxed, again, to welcome me. I can only hope she’ll tap into her heart, opening her arms to her other child one more time.

I’m dozing off, I can’t help it, but she’s not finished: She’s found a photo of our extended family that has writing on the back and she sits on my bed to look at it closely. The faces perplex her; I tell her who each person is. She agrees with my assessment, we laugh at an ugly sweater or untidy beard, and for a moment she seems herself. Then she flips the picture over and starts reading the names aloud. “Huh. I wonder why these names are written here?” she says. Again, she flips the image. “I’m not sure who these people are,” she repeats, staring for a while. Flip. “Oh look, someone wrote on the back,” she notes.

She reads the names aloud again. Turns back to the image. A long pause. Then: “Who the hell are these people?”

——-

Photos:

Top: Photo by Hans-Peter Gauster on Unsplash

Crooked room by Aunt Judy

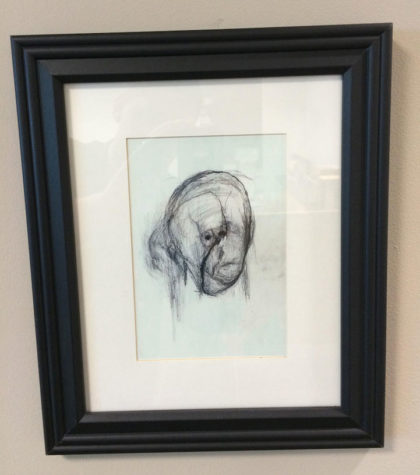

Image of portrait borrowed from MyModernMet.com

Sigh.

We’ve been having conversations about this in my family off-and-on for years because two of my relatives have slowly gone down the dementia slide-of-hell. So it seems like this might be in store for more of us as we age (got a ways to go yet). My mother said that though she would prefer not to live in a retirement home or care facility (she’s fiercely independent) that if this did happen to her, at some point she wouldn’t really know so we could do it if it became too hard. Me, I tell my kids to just take me out into a field and put me down.

God. Of all the ways to die, this is the one I fear the most. Losing my mind.

Thanks for your comment. It is a particularly terrifying way to go…

Thank you for sharing- beautifully written. Very thought provoking!

Dr. D,

But of course your kids can’t do this. My mother-in-law laughed and said the same thing, over and over. In 2011, when she knew she was struggling, she said the same thing again. We lived down the street, we watched her decline, taking care of everything. In 2015, she grew angry and shrill when we gently tried to have the conversation. This happened again in 2016. She agreed to move into assisted living in June – they gently told us after 2 weeks that they couldn’t keep her, she needed memory care. She was terrified of the small, locked unit – she loved the outdoors and small children. So we moved her in with us and our teenagers. It is a very hard thing to face, our decline. And if it is too much for us to bear, our children will bear it.

This is a beautiful post. So sorry for your whole family. Thanks for taking the effort to share.

I’m so sorry for your entire family. My grandmother had alzheimer’s. It was so sad watching her, over the years, slowly fade away. She was always a strong woman, very proud and hard working raising four children by herself right after the depression. To see her fade away without the dignity she was so proud of was painful. When we would visit and she was afraid of us because she didn’t know who we were and why we were there was painful, very painful. I do not want this to happen to me. I am hoping my very healthy diet and constant challenging my brain pays off. Thank you so much for sharing your family’s story as beautifully as you have.

Thank you for sharing this. I am currently trying to mentally accept that this hell is likely in my near future (my dad) and although it is horribly difficult to think about how things might go it is helpful to read about others’ experience with it. I am truly sorry you (or anyone) has to go through it.