I published this story at the beginning of 2017, ostensibly as a way to promote my book. But I keep coming back to read it because the study is just so astounding. It’s one of those wonderful moments in science where the tiniest tweak unlocks a whole new world.  If you read science magazines – and certainly if you read this blog – you know by now that lots of people are talking about placebos these days. They are real, they are scientifically important, they are distracting, they are good, they have something to do with chakras, they are bad, they are the next big thing, they are a bunch of BS.

If you read science magazines – and certainly if you read this blog – you know by now that lots of people are talking about placebos these days. They are real, they are scientifically important, they are distracting, they are good, they have something to do with chakras, they are bad, they are the next big thing, they are a bunch of BS.

In my recent book, Suggestible You, I spend a fair amount of time talking about them and meeting with the luminaries of an emerging field within psychology and neuroscience that focuses almost totally on placebos and the expectations that create them. And yes, they are all of those things and more.

Over the past five (oh, who am I kidding – ten) years working on this project, I’ve tried to draw together a number of themes that all the scientists studying placebos have in common – belief, expectation, pain relief, and the power of subconscious cues. But there’s one thing that ties almost all the modern furor over placebos that I totally missed: Fields and Levine.

Howard Fields and Jon Levine were a couple scientists who, back in the 1970s, showed that the placebo effect for pain was triggered by a flood of internal opioids, similar to the endorphins that give us a runners high, among many other pleasurable experiences.

Almost every scientist I talked to who studies placebos mentioned their seminal 1978 paper. They get mentioned so much in the small world of placebo research that I started to think of them as some kind of mythical creature – the Fieldsnlevine. Just a little smaller than the Watsonncrick. It never occurred to me that they might be real people who put their pants on every day and occasionally pick up phones.

When I eventually called Howard Fields, now a professor at UC San Francisco. I expected a serious scientist, maybe complete with pipe, tweed jacket, and the occasional harrumph. What I got was a hilarious interview with an incredibly perceptive researcher prone to wonderfully sweeping statements and uproarious laughter.

But before I get to that, let me set the scene a little. In 1973, a team of scientists made an odd discovery. It seemed that pig brains contained special receptors for opium. Why, they wondered, would their (and presumably our) brains have a receptor specifically aimed at the sap of a random Asian poppy plant? What are the chances? Unless … well, unless our brains generate a similar chemical.

The race was on to find our internal heroin generator and in 1975 a Scottish team recognized it as a pain-relieving chemical discovered ten years before at UC Berkeley. It was named “endorphin” and quickly became all the rage. Enter our heroes, the plucky newcomer Jon Levine and the more experienced, equally plucky Howard Fields. For them, these endorphins had the potential to open up an incredible ability in our brains to actually diminish the pain we experience.

The pair were working with opioid-sensitive, pain circuits in rat brains and had their eyes set on translating that to humans. But there was one problem. Avram Goldstein of Stanford University, the guy who developed the technique used to find the receptor in the first place, and another giant in the field, Patrick Wall, had shown that endorphins don’t do squat to curb pain in your brain. In a clever experiment, they gave subjects in pain a dose of naloxone, which counteracts the power of opioids. If indeed we had these tiny pain-killing drug factories inside our heads, the naloxone should shut them down and increase our pain.

But it didn’t, the people felt exactly the same as before. Endorphins, though cool, had no effect on humans. “That really let the air out of our balloon,” Fields remembers. “I said, ‘We should drop this. If it doesn’t apply to people then, well, who cares about rats?’”

But Levine was persistent. He and Fields should double check the studies to “see if they are right.” Fields’ initial response was exactly what you might expect from a visionary thinker on the cusp of a daring and transformational discovery: Hell no.

“I was like, ‘See if they’re right? These are like the two major figures in the field! I’m just an assistant professor – I’m just getting started. They’ll kill me!’”

Still, Levine prevailed and the two set to work. What they needed to do was show a pain-killing effect on real humans. They decided to focus on dental patients recovering from wisdom teeth removal because it’s a predictable arc for when the pain starts and stops. They started the way that any good scientist would – take a bunch of people in pain, give half of them naloxone (a higher dose than the other researchers used) and half a placebo.

Sure enough, the people on naloxone felt more pain. The pair wrote it up, published in Nature and patted themselves on the back. But there was a lingering question: Why? What was it that the naloxone was doing? So they did another experiment, this time adding a third group who would actually get morphine.

“That was it. As soon as we included that small group, we could put on the consent form, ‘You might get morphine, you might get naloxone (which will make your pain worse), you might get placebo,” Fields says. “Without the expectation of pain relief, you don’t get a placebo.”

What had been missing was the promise of relief. In all the other studies, it had been a choice between the same pain or more pain. But as soon as you added the possibility of morphine, some of the people would start to expect it and their brains would begin kicking out painkillers.

What was more, the effect would stop as soon as a subject getting a placebo would get naloxone. The drug would only increase the pain if the brain was already engaged in decreasing it. It was a revelation. Until then, people who tried to understand placebos were never fully sure if the effect they were seeing was actually a placebo response but now there was a way to reliably create it in the lab. And a mechanism to explain how it worked.

“That was a really big deal. It wasn’t meant to be. I mean, it was never our intent to study placebo,” Fields says.

The researchers published the study in the Lancet and Fieldsnlevine was born. It would be decades before this mechanistic version of the placebo effect would gather enough momentum to be taken seriously by the wider public. In that time, scientists would tease apart all kinds of placebos (and their angrier siblings, nocebos) and eventually image them in brain scanners.

But it was Fields and Levine who brought placebo and expectation from the world of psychology to the world of brain science. Interestingly, Fields himself didn’t really pursue placebos after that, preferring the broader, more arcane world of motivation in the brain.

He wants to understand the problem that the brain is trying to solve by using placebos in the first place. In other words, why would our brains have a system that causes us to feel something that’s not true? He sees placebos as related to the brain’s primary job, which is prediction. The brain is constantly trying to figure out what to do next and once it makes up its mind, it needs a tool to push other concerns out of the way.

“To me, that’s what’s satisfying,” he says. “Life is all about carrots and sticks. It’s about punishments and rewards. It’s all about learning and adapting to your environment so that your decisions are better.”

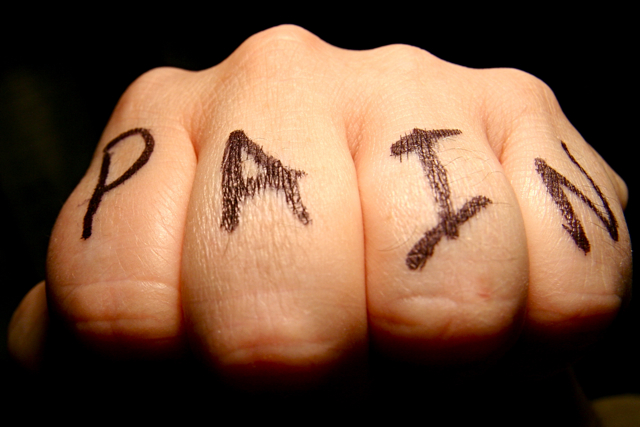

Opening photo credit: Steven Depolo

Support for this project provided in part by the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.