May I introduce James Gleick? He’s been on staff at the New York Times, and has written seven books, including Chaos and Genius (a biography of Richard Feynman), for which he’s won impressive prizes. And he’s just published Time Travel, which Joyce Carol Oates called “another of [his] superb, unclassifiable books.” It’s a compendium of all the explanations, implications, ramifications, aspects, and generally unpleasant outcomes of traveling to the future or to the past.

May I introduce James Gleick? He’s been on staff at the New York Times, and has written seven books, including Chaos and Genius (a biography of Richard Feynman), for which he’s won impressive prizes. And he’s just published Time Travel, which Joyce Carol Oates called “another of [his] superb, unclassifiable books.” It’s a compendium of all the explanations, implications, ramifications, aspects, and generally unpleasant outcomes of traveling to the future or to the past.

§

Ann: When I look at your book-tour dates and places, I see that you’ve mastered time travel yourself, or at least you’ve managed to get from one place to another in unlikely intervals of time. Are you exhausted?

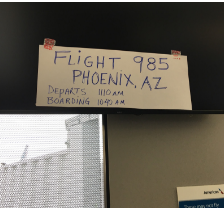

James: Oh, well, I’m fine, thanks, though space travel—the mundane kind, as opposed to the rocket-ship kind—can occasionally feel as disorienting as we imagine time travel to be. After all, jet lag is a kind of time sickness. At least I didn’t cross the International Date Line. I did have an uncanny moment at the Seattle airport when I wondered if I had slipped into a bygone era and was about to board a biplane:

Ann: The book is a nice holdable size with smooth paper and nicely-spaced print; it’s the perfect antidote to cyberspace. Did you have any say in any of these choices?

James: I did! My longtime editor knows that I have some old-fashioned sentiments about books and is happy to cater to that. I also love the book jacket, which is entirely the work of the very creative designer Peter Mendelsund.

Ann: I loved the jacket too, the way the author name fades into the past and the title fades into the future — assuming past is to the left and future to the right. And that’s just the hard copy; the words on the electronic version also slide, disconcertingly. Just like the subject. What were you thinking about when you came up with it?

James: This is one of those questions I can rarely answer. If only every book had a eureka moment. In this case, not only can’t I remember but I can barely imagine thinking to myself, “How about time travel? Is that a book?”

Ann: I can’t imagine thinking that either, nor can I imagine thinking it more than once, but you must have done.

James: I do remember what pushed me over the edge. It was learning (or realizing, or discovering) that time travel is a surprisingly new idea. I had always assumed that time travel was just an obvious and universal human fantasy. But it turns out that H. G. Wells pretty much invented it, in The Time Machine, which is 1895. And even then it took years before “time travel” was a thing anyone talked about. So that was a puzzle! And the more I looked into it, the more I realized that it was part of a bigger picture. Our whole culture, globally, was undergoing a profound change in its understanding of time—what it is, what we can do with it, what it can do to us.

Ann: The culture, the context in which we think about time is already a pretty big idea, but time! Time is a monster! I can almost think in two dimensions, have trouble with the third, and am completely inept with the fourth. How did you get your mind around this stuff? Or do you naturally think in contradictions and loops?

James: I suppose I have always liked riddles and paradoxes, and those are the meat and potatoes of time travel. Contradictions and loops, right! You can’t get away from them. Luckily you don’t have to be a theoretical physicist to enjoy having your mind bent by time-travel paradoxes. Maybe my favorite moment in Woody Allen’s movie Midnight in Paris is when his accidental time traveler, called Gil, meets the young director Luis Buñuel and tries to talk him into making a movie we already know he is destined to make:

GIL: Oh, Mr. Buñuel, I had a nice idea for a movie for you.

BUÑUEL: Yes?

GIL: Yeah, a group of people attend a very formal dinner party and at the end of dinner when they try to leave the room, they can’t.

BUÑUEL: Why not?

GIL: They just can’t seem to exit the door.

BUÑUEL: But, but why?

GIL: And because they’re forced to stay together the veneer of civilization quickly fades away and what you’re left with is who they really are—animals.

BUÑUEL: But I don’t get it. Why don’t they just walk out of the room?

Here’s the essential paradox of backward time travel. If Buñuel gets the idea from Gil, and Gil got the idea from seeing Buñuel’s movie, where did the idea come from in the first place?

Ann: I just can’t deal with that. I think time is like thought: it surely has a physical basis, but understanding it physically doesn’t help a bit.

James: Ha. Is this a question, Ann?

Ann: No.

James: I don’t know if time is “physical.” I agree that it depends on the existence of a physical world: if nothing existed, what would it mean to speak of time? Time seems inextricably bound up with change—some would say time is the measure of change—so if there’s nothing to change, there’s no way to conceive of time.

I have a feeling that didn’t help a bit, either.

Ann: It didn’t. I’m sorry to be so recalcitrant. Though your definition of time in the book made sense to me: “Things change and time is how we keep track.”

James: Not a definition, really. More of an antidefinition. As you see, I devote an entire chapter (“What Is Time”) to the futility of our many efforts at pinning this butterfly to the board.

Ann: Ok then, let’s just declare victory and move on to a question whose answer I have a chance in hell of understanding. Were you saying that the idea of the past and the future as places didn’t always exist, that it developed in the 19th or 20th centuries?

James: As places is the key. The point of time travel is imagining that one can move through time the way we move through space: willfully, and with some control over where we go.

Of course people thought about the past, and they thought about the future. We’ve been reading tea leaves and casting hexagrams and consulting oracles since ancient times. When we go to fortune-tellers, though, it’s usually our own fortunes we’re asking about. The idea of that the future, the whole thing, would be profoundly different from our time is new. It began to come in with the Industrial Revolution, when technology started changing fast enough that people could see the texture of life changing.

When we talk about utopia, we naturally tend to think in terms of the future. (Or more likely dystopia, nowadays.) It’s worth noting that the original Utopia, by Thomas More in 1516, had nothing to do with any putative future. Utopia was an island someplace far away:

Ann: Thomas More reminds me: this book is nearly as full of names and references and other people talking as the splendid Anatomy of Melancholy. It’s like you’ve got a party in there. However did you research this?

James: I’m something of a magpie. I spent a long time on this book (which is fairly short)—four or five years.

Ann: That’s a long time to spend on a short book and I can easily believe this book needed it. And it’s a little reassuring to me as well. Your writing is personal, unintrusive, clear, and dead elegant. I was worried that it just flowed out of you, that you pretty much wrote one exquisite draft and that was it. If that’s true, don’t tell me please.

James: Really, you are too kind. Steven Jay Gould told me that he wrote everything on his manual typewriter, straight through, a single draft. I wouldn’t believe most people who claimed that, but I believe him. As for me, I am an obsessive. There are paragraphs in this book that must have been rewritten twenty times or more.

Ann: Last question: what’s the most unsettling thing about time for you?

James: Same for me as for everyone, I think, whether we’re conscious of it or not. Time is a killer. Time obliterates memory, and then it obliterates us. I came around to thinking that all time-travel, in one way or another, is about eluding death. Seeking immortality.

The modern physicist sometimes tries to offer comfort by saying our sense of past and future is only an illusion; our existence is a four-dimensional path in a four-dimensional space-time continuum. We don’t grieve for the all the time before we were born, so why lament the time after we die?

_________

Photos: departure notification, by James Gleick; Isola di Utopia, via Wikipedia