In February, I wrote about a story I never wrote. This is another one of those.

It all started when I reviewed tampons for The Sweethome. As part of the review, I was trying to figure out what the actual dimensions of the human vagina were. I knew that vaginas come in all shapes and sizes, but I thought that there must be some average set of dimensions out there. There certainly are studies on this for penis size and shape (a lot of them, in fact). So I was surprised when I couldn’t really find much on the average dimensions of the human vagina.

All I could really dig up was a set of studies done in the late 1990’s and early 2000’s by a woman named Paula Pendergrass. Pendergrass published a handful of studies about the shape of the vagina, which she measured by doing plaster casts of willing women. And what she described in her work was actually a set of different vagina shapes: the conical, the parallel sides, the heart, the pumpkin seed, and the least fortunately named slug.

This was a surprise to me, and I like to think of myself as someone who knows a lot about vaginas. But five different shapes? I had never heard of this before.

What was even more surprising to me, was that there was that after Pendergrass stopped doing this work, that was it. I couldn’t find anything after her papers about this. Nobody continued to measure the shapes of the human vagina. No one tried to cast more women to see if Paula’s preliminary finding that women from different ethnic backgrounds might have different shapes. Nothing.

And it’s not like this is purely a question of raw, unimportant anatomy. In her papers, Pendergrass pointed at some places why these vagina shapes might matter. Perhaps different shapes impacted drug delivery, perhaps they made certain sexual positions more or less pleasurable or comfortable, perhaps they impact how reliable a sponge contraceptive device might be.

But even if there was no clinical significance, think of it this way: if there were five distinct shapes of human penis, how many studies do you think there would be on it? My guess is more than a handful done by a single researcher.

So this was the story I pitched. That there was this very fundamental thing about human vaginas that simply hadn’t been studied. That it might impact some fundamental parts of a woman’s life, and that there was simply nobody doing the work to find out.

Great, story sold.

Step one: contact Pendergrass. Which was slightly more difficult than I expected, since she’s now retired. But I tracked her down and called her up at her Arkansas home, to hear about her work. It all started when she was in medical school, she told me. She got interested in the vagina after her own issues with fibroids. And she actually had the same question I did: what was the shape of the human vagina? And, like I had found, the papers out there were vague and conflicting.

So she drummed up some interest from her advisors and a funding agency to try and do some casts. First she cast a cadaver, and when that went well she decided to move on to living humans.

And like many scientists before her, she started her study with a subject she knew well: herself. With the help of her husband they figured out how to use dental latex molds to create a vaginal cast. (One thing she learned through that trial and error cast: make sure to put a tampon into the cast with the string hanging out so you can get the thing out of your vagina.)

Once she had the method down, she started studying more women.

She told me about how the work progressed, what she learned, her funding issues, and then ultimately that she retired after a long career as a doctor and researcher. All of it was super interesting, I thought. And then I asked her: okay, so, why hasn’t there been more work on this since you stopped doing it? And she had a few answers. There’s no market for this data. Companies that manufacture vaginal products are looking only to confirm that things like tampons fit inside. They don’t care much about the specifics beyond that.

But the big reason she highlighted was the one that made me both sad and angry. When she was doing the work, people were grossed out by it. “It’s off-putting to a lot of people, and I’ve had trouble with it since I started,” she said. “People who were embarrassed I was doing this, They said I was a a dirty old woman doing this.” A dirty old woman. For wanting to know the shape and size of the human vagina. I was sad, and angry, and ready to finally tell her story.

Okay, step two: talk to outside sources. And, as you probably expected, this is where it all fell apart.

To get an outside take, I talked to two OBGYNs. And I showed them the papers. And they basically just shrugged. “Vaginas are changing shape all the time, depending on musculature,” said Dr. Ruth Ann Crystal, an OBGYN. You could cast the same vagina twice and get different looking shapes. And having a baby can stretch the vagina in new dimensions, so casting a person before and after they’ve given birth will result in different measurements too.

Crystal says she’s not surprised that different ethnicities might have differently shaped vaginas either, just like eyes and noses vary between people. Sure, different women might have different shapes, but she just didn’t think it mattered much.

Neither did Dr. Jen Gunter, another OBGYN. “I’m not sure it would be clinically relevant,” she said. “People can fit seven pound babies, and at some point the baby’s head is in there, and the shoulders, and the body, and the vagina can fit them all. It’s more like a stocking, it’s meant to stretch.”

The one thing that both Crystal and Gunter said might be impacted is which positions are best, but they both pointed out that sex is more than just figuring out the “optimal” angle for which a penis can go into a vagina.

Essentially, there are probably different vaginal shapes, but what shape you have probably doesn’t matter.

So, there’s not really a story here. I told my editor. We agreed it was a dead end.

But I still feel somehow… sad. Not about my story, although that paycheck would have been nice since I did all the reporting. But more that Pendergrass was shamed for even thinking about doing this work. That people called her a dirty old woman for just wanting to know what the shape and size of the human vagina was.

So this story has, a coda I guess. I read through Pendergrass’s papers enough times, and thought about the process enough and it dawned on me: I could do this. I could cast my own vagina, and at least carry on some of Pendergrass’s legacy. So I went online and i ordered a dental casting kit from a medical supply outlet. It’s sitting on my desk here. And this weekend I’ll enlist my very patient (and far less impulsive) partner to help me figure out what the inside of my vagina looks like. Wish me luck.

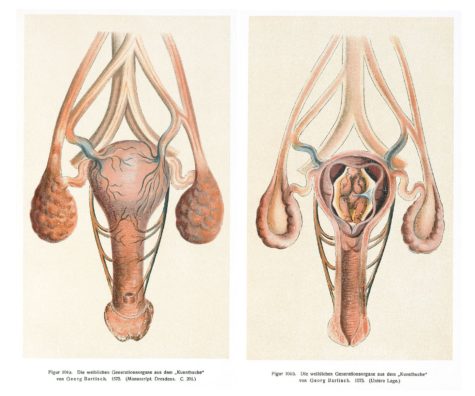

Top image from Wellcome Images.

Women’s invisible “parts” have been considered dirty (and thus worthy of vile names and jokes) for a very long time. What state legislature was it that came unglued when a woman used the word “uterus” to them? And men in the Texas legislature are so mortally afraid of tampons that they had women’s purses searched and any tampons confiscated before allowing the “terrorists” into the legislative chambers. So it’s not surprising that Dr. Pendergrass was called a dirty old woman, though it was certainly an ignorant remark.

It’s even more depressing and angering that women Ob-Gyns would consider knowing the resting shapes of women’s vaginas unimportant because the vagina is capable of stretching. So is the stomach. So is the gut. So is skin. Doctors don’t consider the shape of an empty stomach unimportant because it can hold a large amount of food. Or the shape of an empty gut unimportant. So why is the natural un-expanded shape of a vagina unimportant?

In part because women are still thought of as mere conduits for reproduction: as long as a penis and some sperm can get in, and a baby can get out, that’s all that matters. Any vagina will do; they can stretch. It doesn’t matter what it was before, what its natural shape was, whether that shape is ever recovered after intercourse or delivering a baby–its purpose is for someone else, man or baby, to deform and it will stretch to allow that. That it might be less painful and more pleasurable for the women the vagina is part of, if the shape were known and certain positions adopted or avoided. or that some shapes might be particularly ill-suited for shoving a baby through…isn’t important as long as it works. She doesn’t have to enjoy any of it; her job is just to push out the next generation. It’s only recently, after all, that testing of drugs extended to women, rather than making men the norm for everything (with the not-surprising finding that women do not metabolize everything exactly like men.) And it was only last year that a major health-tracking app failed to include a way to chart menstrual cycles–a very important health tracking issue for over half the population. Women’s body size isn’t considered in items intended for the use of both sexes (astronaut suits, smartphones) or in the portions served in restaurants, where huge servings for already obese men are the norm, and women have the choice of requesting a doggie bag or wasting food. At the same time, heavier women are ridiculed and penalized; sturdy and comfortable clothing for larger sizes is simply not available.

Obviously I take issue with this attitude. Female reproductive organs aren’t dirty. Female reproductive organs are not something to shrug off with “it’s like a stocking; it stretches.” Women’s discomfort and pain related to their reproductive parts should not be ignored, disbelieved, or minimized. And the natural size and shape of women’s vaginas–both before and after childbirth–should be of interest to clinicians who can think beyond “if it stretches around a baby, that’s all that matters.” The neglect of this and other basic research has almost certainly affected fertility and other health issues in some women.

It doesn’t seem right that flexible equals shapeless. An engineer could probably be enlisted to look at the various tensions as it is put under stress and stretched. Good luck, Rose.

If it goes well, maybe you could do it a bunch of times over the course of a year to see if it does change shape, thus proving or disproving that theory. Who knows, you could even write a paper yourself.

In a similar vein, have such studies been done on the stomach? It’s the closest thing I can think of that would have some inherent default shape but that changes drastically throughout the day and our lives…. Excellent writing and THANK YOU. What’s your type of the 5? 🙂

Not sure this is a dead end. A search for citations shows 38 alone for Pendergrass’s 2003 paper, ‘Surface area of the human vagina as measured from vinyl polysiloxane casts’, including 3 citations this year alone. These are respectable numbers, so I wouldn’t say that there isn’t anyone following up on her work.