When I travel outside the US, I use an app called OffMaps. It loads up a map of whatever city you chose onto your phone, so even without service I can at least have some sense of where I’m going. There are lots of apps that do this, and probably ones that do it better than OffMaps, but it’s what I’m used to. And there’s a feature that OffMaps offers that I really love. You can chose to download just the map, or you can chose to download the map and all the Wikipedia pages related to that map.

This means that I can walk around in a place and read about all the stuff I’m seeing, at least as far as Wikipedia has entries on things. It also means that I can browse through all these Wikipedia entries looking for interesting monuments or tidbits.

This summer I went to Montreal to see some Women’s World Cup games. And while browsing OffMaps I saw an entry for something called Goose Village. Already in my mind were images of a whole delightful village full of geese, waddling along tiny cobblestone streets. But when I clicked through to read the entry, I learned that the reality was much darker.

Some Irish history books call the year 1847 “Black ’47.” It was a dark time in Ireland. Crops were failing (most notably the potato) and people were sick, dying and fleeing if they could. Many of them boarded ships to Canada and the United States, but the trip was rough, and the boats were so riddled with disease that they were nicknamed “coffin ships.”

In 1847, a ship called the Syria landed at Grosse Isle, in the Gulf of St. Lawrence in Canada, downstream from Quebec City. Onboard were around 245 passengers, and as many as 125 of them had typhus.* Nine had died during the 46-day crossing from Liverpool, England. The Syria wasn’t unusual either. By the end of 1847, 406 ships anchored off Grosse Isle carrying around 75,000 Irish immigrants trying to make their way into Canada. And almost all of these ships anchored full of typhus cases.

Grosse Isle was just an entry point, much like Ellis Island in the United States. But Grosse Isle became a quarantine station for these typhus cases, and soon the island couldn’t take in the flood of sick travelers it was receiving and some of them were moved to an area called Windmill Point, in the southwest of Montreal. These transferred immigrants were housed in three “fever sheds” — buildings designed to house the sick and dying, to keep them away from the population at large. These were big buildings usually made hastily of wood measuring 150 feet long by 40 or 50 feet wide, lined with beds.

But pretty quickly three sheds wasn’t enough, as thousands more immigrants landed in Windmill Point. Eventually there would be 22 sheds on the site, where the sick were tended to by a team of 40 nuns. Of those 40, thirty would catch typhus, and seventeen would die. Typhus had spread to Montreal proper too, nearly 11,000 people in the city were sick that summer, and as a restul tensions over this flood of Europeans were high. At one point, a mob threatened to attack the sheds and throw them into the river.

By 1848, when the outbreak ended, somewhere between 3,500 and 6,000 people died in the outbreak. “The mortality here along the riverbank of Point St. Charles was appalling,” wrote Reverend John A. Gallagher in 1936.The number of bodies was so overwhelming that workers dug trenches on site where they buried the bodies.

But despite the mass casualties, the grave and the site was largely forgotten once the outbreak ended. In fact, nobody really knew that bodies were even buried there until 1859, when construction workers starting to pave the way for the Victoria Bridge, came across bones. Lots of bones. According to some accounts, many of those construction workers were themselves Irish, and they petitioned to have some kind of monument put up to memorialize those who were buried there.

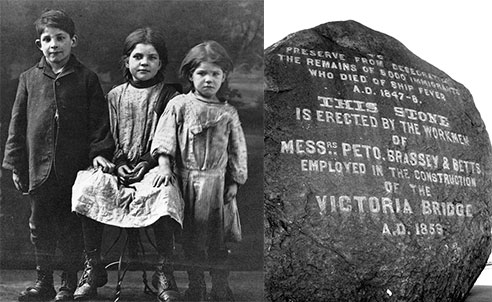

It worked, and on December 1, 1859, a huge black stone (now known as The Black Rock) was placed on the site that read:

To Preserve from Desecration the Remains of 6000 Immigrants Who died of Ship Fever A.D. 1847-48

This Stone is erected by the Workmen of Messrs. Peto, Brassey and Betts Employed in the Construction of the Victoria Bridge A.D.

Over the years, the area was renamed from Windmill point to Victoriatown and then to Goose Village. And over those years the land was built on and settled. By 1960, Goose Village was home to about 330 families, most of them Italian Canadians. But it wasn’t a wealthy area and the mayor of Montreal at the time, Jean Drapeau, reportedly hated the little village. Montreal was preparing to host the 1967 World’s Fair (also known at Expo 67) and Drapeau worried that the little village would make Montreal look bad.

So he had it demolished. In 1964, the whole village of Goose Island was bulldozed. There are still people living in Montreal today who grew up in Goose Village. In 2007, Canada.com spoke with one of those people who they simply call Martin:

Not a trace survives of the neighbourhood where Martin grew up. Gone are St. Alphonsus School, Piche’s store, Zaleski’s, Diorio’s, the No. 2A bus that wound through the Village with bus driver Roland (Flirt) Desourdie at the wheel. The stockyards are gone, and the reeking tannery; the steel rolling mill and the cafe that served the city’s best fish ‘n’ chips.

The only things spared in the 1964 demolition were the fire station, the train station, and The Black Rock.

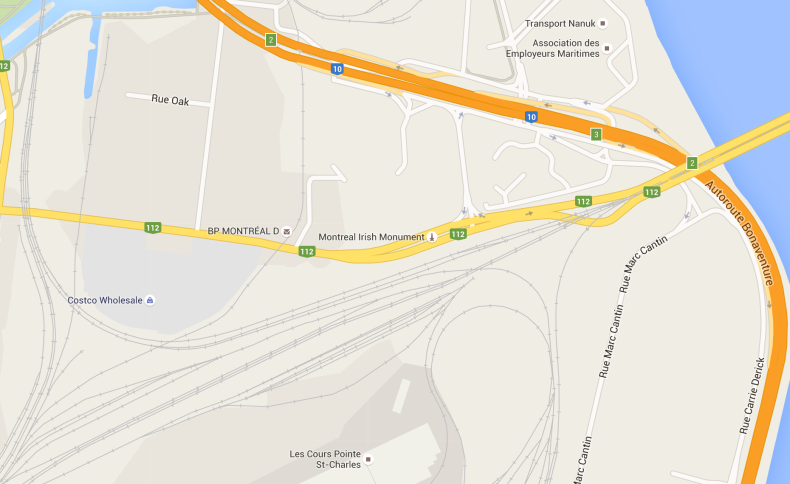

So of course I wanted to go see what was left of Goose Island and The Black Rock. We grabbed bikes from Montreal’s bike share system, and pedaled out over the bridge, across some very busy streets, and got very lost in a construction site. After several loops and close calls, we came to a parking lot where people were racing tiny tricked-out go carts. A monument? A big black monument? Oh, yeah, they said, that way, just across the parking lot.

And it was. But it wasn’t quite what I expected.

The Black Rock currently sits in a median that divides two busy streets. You have to dodge traffic to get across to it. It’s weather worn, and it’s hard to even get a picture of the thing without a billboard behind it, or a car’s blurry mass in front of it. All the photos you see of The Black Rock are closely cropped, just pictures of the inscription. This is why:

This monument to thousands of Irish who came to Canada trying to escape famine and death in Ireland, only to die terrible deaths in long wooden sheds on foreign soil, is being swallowed by development. And not even the good kind of development. This is the crappy kind of development that creates huge parking lots for no obvious reason, and continuously open construction sites that never seem to construct anything.

Irish Central described it this way: “The grave now sits in an industrial zone at the foot of the Victoria Bridge in Montreal with little indication that it holds host to the grave of 6,000 Irish and Canadian people.”

There are people currently trying to change the sad state of The Black Rock. The head of the Montreal Irish Monument Park Foundation, which was established in 2012, is petitioning the city to turn this little patch of land into a proper memorial park with a little museum and a green space. And they currently have a sympathetic mayor in Montreal, who himself has Irish heritage.

Even without the big park, the stone is appreciated at least once a year. Every July the Ancient Order of Hibernians conducts a “Walk to the Stone” event, where hundreds of Montrealers walk from St. Gabriel’s Church north east along the 112 to the monument. This year, Justin Trudeau, now the Prime Minister of Canada, lent his support.

Certainly there have been greater tragedies in the history of humanity. Certainly there are greater tragedies that have no monuments at all. But I couldn’t help but feel a little sad about how unceremonious The Black Rock was, sitting there in the median of a thoroughfare. This was once a village with a famous bus driver (every account of Goose Island I found referenced the No. 2A bus and its driver, Roland Desourdie). There are thousands of bodies under that road, and I wonder if anybody driving on it has any idea.

*Different accounts I’ve read list pretty different numbers for how many people were on the Syria, and how many of those people had typhus. Some places say the ship held 430 thyphus cases, while others put the total number of passengers at 245 or 241. Some say that there were 125 sick people on the boat, other places say 84. Everyone seems to agree that nine people died in the crossing.

Top Image: Left, Goose Village children, 1910, McCord Museum. Right, The Black Rock, douaireg, Flickr.

You write: By 1948, when the outbreak ended, somewhere between 3,500 and 6,000 people died in the outbreak.

You mean 1848

You are right! That would have been a very long outbreak. No more eggnog for me. Thanks for pointing it out! Corrected.

Rose, have you read Andrea Barrett’s story, Ship Fever, in her collection of the same name? http://andrea-barrett.com/ship-fever/ it’s the same story, only fiction and beautifully written.

Thank you for this. I lived most of my life in Montreal from 1974 to 2011 (when I moved to Halifax). And yet I had NO IDEA about any of this. So as to your pondering as to how many people drive those roads while never knowing of the bodies beneath them, I’d say it’s quite likely a fair number.