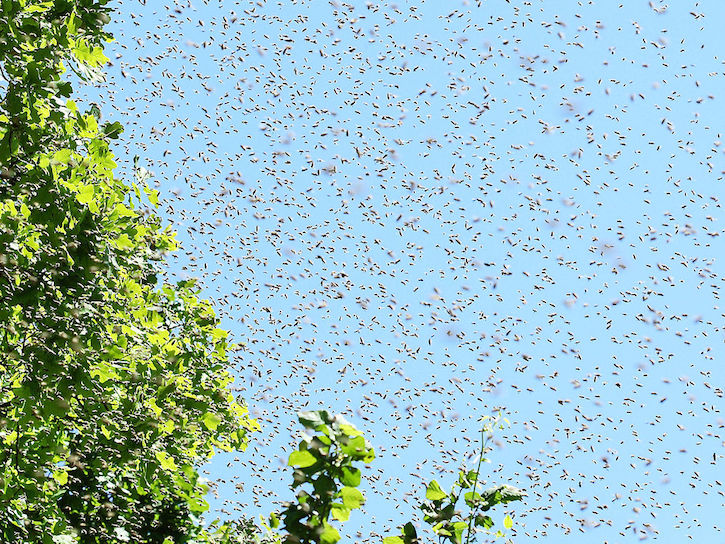

Early the other morning, I woke up to a strange humming noise. My first thought was the ceiling fan motor was petering out, but it turned out the sound was coming from outside. So I stepped out onto my little balcony for a look, and listen. The hum hummed louder. It took a minute before I could focus on what was in front of me, but then suddenly I saw them. Bees. Thousands of bees. Maybe tens of thousands. The massive swarm hovered just there, not terribly far from my face, a full-on cyclone of insects.

Early the other morning, I woke up to a strange humming noise. My first thought was the ceiling fan motor was petering out, but it turned out the sound was coming from outside. So I stepped out onto my little balcony for a look, and listen. The hum hummed louder. It took a minute before I could focus on what was in front of me, but then suddenly I saw them. Bees. Thousands of bees. Maybe tens of thousands. The massive swarm hovered just there, not terribly far from my face, a full-on cyclone of insects.

It was an awesome thing.

It wasn’t a total surprise. My neighbor keeps three honeybee hives in his backyard (and shares the spoils all around, probably to shut up those ready to complain). Apparently, there had been a coup of sorts in one of them: Occasionally, about half the workers in a hive snatch up the queen and find a new palace, slamming the door on their way out.

Imagine trying to make a decision about real estate with 10,000 opinions to consider. Fortunately, bees don’t work quite so independently. To prove it, the swarm moved as a single thing, rising and falling with its contours intact. Within, of course, it was a madhouse of movement, bees zigging and zagging every which way like popcorn in a popper. But it all held together in a beautiful way.

Finally, apparently having decided my yard lacked the homey feeling bees like, the whole massive thing rose like a single balloon and moved off over the trees. The hum faded like a lawnmower powering down. (It was pretty early on a Saturday for mowing, but bees I can forgive.)

I’ve been writing about honeybees (and other pollinators) for a dozen years, starting with the first round of “Colony Collapse Disorder” that got us all thinking about how much we rely on them for our food. (A lot.) But this isn’t about the pollinator crisis. You see, before this day I was a swarm virgin. This was my first sighting of a textbook-perfect swarm. And watching it stay whole despite all the moving parts got me thinking. I suddenly decided that a bee colony is sort of…mammalian. Almost human! It’s a stretch, but hear me out. And humor me a little.

First off, bees are hairy. Their hairs are made of chitin instead of our keratin, but still, it’s furry stuff. And yes, bees are cold blooded, but the hive as a whole thermo-regulates. It’s able to warm up by way of individual bees’ metabolic activity and muscle contractions that resemble shivering. So the heat comes from within. Kind of endothermic, isn’t it? (By the way, researchers just discovered a warm-blooded fish, the first known. Cool.)

Now, it’s true that bees lay eggs. But they take care of their kids. Mom (Queen) has a whole village of nannies. Nannies feed the young a sort of milk (royal jelly). Moms and drones (reproductive males) make love a bit like we do, albeit in midair. Moms are a little bit slutty, having many partners in a row—certainly not unheard of in our own colonies.

Full disclosure, though: The tip of the drone’s penis rips off and blows into the queen’s reproductive tract during sex. Which doesn’t usually happen when people get it on. But still, there are parallels. Like this one: Those sexual males just lie around all day, unemployed, watching TV, waiting for their big moment in the sky. After sex, they die. (See above penis mishap.)

And talk about loyalty to family! After Mama’s one wild night, the colony truly treats her like royalty…better than many of us treated our mothers, no doubt. Her kids stick around, helping around the house, taking out the trash. Maybe they complain about boring chores or sharing rooms with hundreds of siblings, maybe some get grounded. Who knows? But most grow up to have real jobs, as nurses, food-deliverers, construction workers, janitors, guards, morticians. A few necessarily turn into those drones, sprawled on the sofa, drinking directly out of the milk carton, waiting for sex. It’s all so…familiar.

And eventually, when the house gets too crowded and the queen becomes careworn and floppy in the upper arms, its time to find a new home for herself and the most loyal of her family. Maybe a nice condo in the city. As for the rest of them? They can just stay behind in that crappy old hive and who cares that there’s a new, younger queen taking over the old queen’s bed. Bitch.

So…honeybees. Every hum has a story.

Top Photo: by Waughsberg, via Wikimedia Commons

Bottom Photo: CSIRO [CC BY 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Wonderful Jenny! What a thrill to experience a swarm. Great writing.

You mentioned that a drone’s penis gets ripped off, when bees mate, and “blows” into the queen’s reproductive tract. Does this kill the drone?

If yes, isn’t that a rather inefficient method of fertilization? Each father dies after just one round of sexual intercourse. The hive’s resources will be directed unduly towards raising fathers if that is the case (Since we’ve all heard of how often a queen lays eggs). I think that’s rather absurd. Or maybe I’m missing something somewhere.

If not, the drone (father) has just one chance at fertilizing the queen. And since the penis itself is not the site of spermatogenesis, there is a possibility of fertilization not taking place and the drone who is now penis-less doesn’t get another shot at it.

I’m no expert on bees. Please correct me if my understanding of this is fundamentally flawed somewhere. 🙂

You make excellent points. But my understanding, from reading multiple reputable sources, is that honeybee drones commit sexual suicide…each one performs his task a single time. The tip of the penis ruptures from the powerful ejaculation, and the bee dies soon after. The Queen mates over and over on that one night, leaving a dozen or more dead drones on the ground. She stores the sperm and uses it for the rest of her life. Perhaps the fact that the Queen lays so many eggs makes this scenario more efficient than it sounds. So, even if a drone gets just one chance, he makes a lot of babies in the process. If any bee expert reads this and wants to comment, please weigh in!

There’s usually about a hundred drones lazing about my hive..more in a really booming hive. And any time a hive goes queenless, some workers will start laying many many drones..so there is no lack of lazy boys for mating, despite the predominance of working females. We beekeepers routinely kill mass quantities for mite prevention and she still lays more..

When the hive senses a dearth in nectar availability they will drag all the men it to die, and in September all the guys are pushed out…so losing 20 for each successful mating is but a drop in the bucket.

A good queen will pump out 500 drones for a season at least. And those will have the genes of all her former lovers to spread around. She will not mate with her sons..supposedly..but I don’t know how anyone checks.

I would think those lucky few had a good time as compared to their brothers that we play with and experiment on, and sacrifice for the colonies health..as well as the fickleness of their sisters love .

Also, just for fun, though it isn’t TGIPF, a drone bee has the highest rate of junk to body mass than other animals. That’s one of my fun demonstrations to a crowd is to push it out of his body..I learned that on an artificial insemination video.

But 10 drones should fertilize enough of the queens eggs to lay for a couple years of laying 3000 eggs a day. Many keepers replace her every year with a new one thinking New is better, though I like to let mine continue since her life of constant child bearing has got to suck enough that she shouldn’t be worried about that too..and I’m trying to breed queens to survive in NE Ohio winters.