The room is plain and cloaked in shadow, save the single pool of light draped over a hardened criminal. Facing the her is a meaty lug of a detective with a ketchup-stained tie and hairy knuckles.

The room is plain and cloaked in shadow, save the single pool of light draped over a hardened criminal. Facing the her is a meaty lug of a detective with a ketchup-stained tie and hairy knuckles.

“This doesn’t have to go bad for you, Jenny,” the larger man growls. “You work with us and I can put in a good word with the D.A. Get you a deal.” Jenny stares hard at the wall-size mirror across from him.

“Look, Jenny,” says a skinnier cop sitting near the door, “if you don’t flip on your cousins, your kid’s looking at a life sentence of autism. That’s hard time. Jenny’s hand flinches almost imperceptibly at the word “autism” but she kept her stare fixed.

The fat man jumps in, as if on cue. “But you implicate your cousin Tony and his gang, you’re looking at – worst case scenario – a little measles for the kid. Hell, chances are, he walks outta here free and clear.”

“So what do you say?” the other one says. “Better yet, what do you think Tony will say? Hey, we got him in the next room. Maybe we offer him the same deal, see where it gets us. I bet he turns on you before I even finish asking.”

The detective lumbers to the door and without turning says, “When your little boy’s got autism, don’t say we never gave you a choice.” As he pulls the door, a voice behind him squeaks.

“Wait. Wait, don’t. Come back. My kid can’t do autism. Let’s talk.”

And there you have it, one of the most important and enduring ideas in all of game theory: The Prisoner’s Dilemma. For those who missed A Beautiful Mind, game theory is a field that tries to quantify the various strategies that humans use every day to shape society.

The Prisoner’s Dilemma is one of the field’s most enduring and interesting paradoxes. It shows how – even when it’s in their best interest to work as a team – totally rational people will go it alone and screw everybody involved. It’s a surprisingly powerful tool for understanding and predicting all manner of human behavior. Entire economies have risen and crashed based on it and, as you probably guessed, it perfectly explains our current predicament with the anti-vaccine movement.

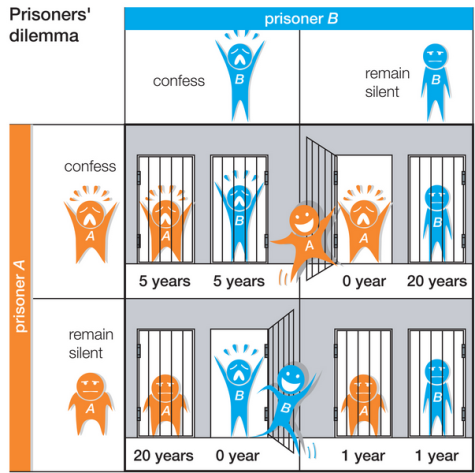

The Prisoner’s Dilemma provides a very basic quandary. If every member of the gang keeps his mouth shut, they all get a slap on the wrist. If everyone squeals, they all go to the slammer. But – and here it gets tricky – if one of them blabs to the cops, he gets off scot free while his buddies go away for a really long time.

It looks a little like this:

Now, what does this have to do with economies and vaccines? Whether you are talking about two guys in jail, a city, state or a massive country, the Prisoner’s Dilemma shows that a sizable segment of the population will sell out their neighbors when the going gets rough.

This idea is often called “free riderism,” which is easily my favorite “ism” so far in 2015. Free riders take all kinds of forms. A free rider may be that roommate who never cleans up but gets to live in a clean house. In class, it’s the guy who skips working on a group project but takes the A with the rest of the group.

On a national stage, free riding can be disastrous. Tax evaders are free riders because they don’t pay for, say, our national defense but get protected from invasion anyway. In another classic dilemma, free riders graze their sheep on common pasture land but take a little extra time – maybe sneaking out at night, leading to collapse and no or diminished pasture for everyone.

Similarly, when everyone gets vaccinated, we all benefit from “herd immunity” and a lot less smallpox or polio. In much the same way, we lose our herd immunity — which protects infants and those who can’t get vaccinated — when immunizations levels drop below 90%.

So the anti-vaxxers have chosen an anti-social path over a pro-social one. By not shouldering their portion of the load (getting shots with minimal risk), they have increased the risk for the rest of the gang. But in the mind of an antivaxxer, keeping your mouth shut (ie: getting a child vaccinated) is a bigger risk than blabbing (avoiding the shots).

So why does game theory go to such lengths to draw out bizarre analogies? Well, once you understand a societal glitch like this, you can prescibe a solution. And as it happens, game theory provides four ways out of the Prisoner’s Dilemma. The first is obvious – simply correct the mistake that creates the problem in the first place. Make the antivaxxers understand that there is no danger from vaccines. It would be a little like a lawyer breaking in on the interrogation and telling Jenny that the cops don’t have a case. No danger, no difficult choice, problem solved.

So why does game theory go to such lengths to draw out bizarre analogies? Well, once you understand a societal glitch like this, you can prescibe a solution. And as it happens, game theory provides four ways out of the Prisoner’s Dilemma. The first is obvious – simply correct the mistake that creates the problem in the first place. Make the antivaxxers understand that there is no danger from vaccines. It would be a little like a lawyer breaking in on the interrogation and telling Jenny that the cops don’t have a case. No danger, no difficult choice, problem solved.

But I sense that if that was going to happen it would have before now. The second would be community cohesion. Instead of a lawyer coming in, it would be Jenny’s mom telling her she has to take the fall for the good of the family. Loyalty kicks in and she fesses up (and gets the shots, much the way Americans did with the early polio vaccines, which were also seen as dangerous). This would mean that anti-vaxxers would have to admit that vaccines – while still dangerous in their minds – are a necessary way to prevent epidemics.

Sadly, this only works in a cohesive group, like a family. These days the phrase “fellow Americans” doesn’t hold the weight it once did. And given our polarized, splintered and squabbling society, I can’t think who would have enough trust from the prisoner to play the part of that lawyer (except maybe one of the leaders of the anti-vaxxer movement having the courage to reverse his/her statements).

That brings us to the third option. A government can step in and force the issue by changing the calculus. We are sort of doing this already. By banning unvaccinated kids from attending school or playgroup, we raise the cost of choosing to be a free rider and push the scales toward vaccinations. So the penalty for antisocial behavior gets higher. Of course, that also creates an incentive to lie and tell people your kid has his shots.

That brings us to the last way out of the Prisoner’s Dilemma – the nuclear option. Simply do nothing. Right now, to misinformed parents, the slim chance of a few red spots on their children’s skin seems a better risk that a lifetime of autism. But as epidemics spread and they see actual children dying of preventable diseases, the scales will shift. It’s a little like Jenny realizing that if she rolls over on her cousin, she’ll implicate herself in a second crime that will land her on death row. Now she has no choice but to go with the good of the group and hope her buddies don’t squeal.

Photo Credit: Shutterstock and Encyclopedia Britannica

Special thanks to Liz Vance for explaining basic economic theory on a Sunday morning.

OLG I love this post! Sadly, I’m afraid that it would be too elaborate to grasp for the anti-vaxers among my acquaintances

I’m not a mathematician or game theorist but as I understand it, these ideas demonstrate that someone can be highly intelligent and rational and still do something seemingly nuts. “Nuts” is the technical term, I’m told.