Charles Hard Townes died a week ago, aged 99. He was a physicist at Berkeley who came up with the principle of the laser; at age 98, he’d stopped coming into the office every day. His obituaries are thorough and their praise is justified. I’d met him for reasons the obituaries don’t mention. He helped set up the Jasons, a group of well-regarded physicists who give the government advice, such that the advice they gave would have no conceivable benefit to them. And he helped get a classified technology declassified so the astronomers could use it to change astronomy. Both these things were important, with wide and deep effects, and Townes gets little notice for what he did; nor did he ask for it. He seemed just as happy to make things happen.

Charles Hard Townes died a week ago, aged 99. He was a physicist at Berkeley who came up with the principle of the laser; at age 98, he’d stopped coming into the office every day. His obituaries are thorough and their praise is justified. I’d met him for reasons the obituaries don’t mention. He helped set up the Jasons, a group of well-regarded physicists who give the government advice, such that the advice they gave would have no conceivable benefit to them. And he helped get a classified technology declassified so the astronomers could use it to change astronomy. Both these things were important, with wide and deep effects, and Townes gets little notice for what he did; nor did he ask for it. He seemed just as happy to make things happen.

I inteviewed him for hours over two days in 2002, when he’d just turned 87. He sat comfortably in his office chair, windows all around overlooking the green campus. He was dressed as physicists of a certain age dressed: slacks, white shirt, jacket. His shirt collar was a little askew and his slacks rode up toward his chest. His manner was open and courtly. He was a master a giving the devil his due – “that’s very natural,” he’d say, “you might say it’s stupid, yes, but that’s the way humans behave, some of them.” He told stories the way Southerners do, a call-and-response that gets the listener right at the scene: “Jason also is not going to take that. So they say no. Well then what does he do? Can he back down? Well, a sensible person you might think would back down. But you know, so many people who just can’t back down.”

Townes had begun his distinguished academic career at Columbia but ten years into it, in 1959, he interrupted it to work for a couple of years at the Institute for Defense Analyses (IDA), a defense research center: “At that time, we had just been through the Sputnik crisis and Washington was very eager to get more scientific and technical advice. I felt such an obligation, I went down to Washington. I agreed to do it for two years. I thought two years was the minimum time to do it well and I could stand that much.” While he was there, he heard of a group of physicists, academics who wanted to give physics advice on defense issues. The trick would be to keep the group useful, trustable by government, and independent, that is, nothing to gain or lose by their advice.

So Townes arranged to get the physicists unusually high clearances, “remarkable clearances,” he said, “clearance to look at almost any secret project, across the board.” Then, since some of these physicists were open, even mouthy, about their liberal leanings in this post-McCarthy era, Townes arranged for the group to have some well-known conservatives as senior advisors, including Edward Teller, John Wheeler, and Eugene Wigner. And finally, he made a clever administrative move: instead of contracting the group to the defense department, as the department wanted, he set them up as a private nonprofit entity, administered by IDA, which would contract out to whomever it wanted to. Jason’s ability to give advice based on science regardless of politics and with no conflict of interest, was at the time unique in the world: and was one reason it’s still alive and useful after 55 years. At IDA, Townes said, “I would say that is undoubtedly the most important single thing that I did.”

About 20 years later, Jason was working on a problem the Air Force had with the atmosphere distorting the images of potential enemy satellites. The Jasons invented a technology to measure the distortion, called a sodium laser guide star, and the Air Force was so happy with it they classified it so highly that for a while even the inventors didn’t have access to it, let alone the entire community of civilian astronomers which had the same problem with the atmosphere distorting not satellites but stars and galaxies. The process of declassification was extremely lengthy and had many authors, but certainly one of them was Townes.

About 20 years later, Jason was working on a problem the Air Force had with the atmosphere distorting the images of potential enemy satellites. The Jasons invented a technology to measure the distortion, called a sodium laser guide star, and the Air Force was so happy with it they classified it so highly that for a while even the inventors didn’t have access to it, let alone the entire community of civilian astronomers which had the same problem with the atmosphere distorting not satellites but stars and galaxies. The process of declassification was extremely lengthy and had many authors, but certainly one of them was Townes.

Townes had by then moved his research from lasers to astronomy, had learned from the Jasons about the sodium laser guide star, and was keeping track of its progress by regularly visiting the Air Force scientists developing it. He talked to, as he says, “some high official” in the Pentagon, urging that the guide star be “opened up.” One story goes that the high official was the President, then the first George Bush, who reportedly said, ‘Well ok. If Charlie said it was something we need to do, I’ll sign it.'” I have no idea if that’s true and when I wrote and asked Townes later about it, he waffled in the most politic manner: “I remember some such statement about the President, but don’t really know what he said anent adaptive optics.” Later I looked up “anent.”

But the sodium laser guide star was indeed eventually declassified and opened up for astronomy. Townes happened to know that the American Astronomical Society had a meeting coming up and, he says, “I felt it important and sensible for [the Air Force scientist] to be invited and give a talk.” He arranged for that to happen, then sat at a panel table, leaning forward to watch the talk which, he said, “was quite spectacular.” Afterward another astonomer who’d been working fruitlessly on a similar system and who was scheduled to give the next talk “then came up to me and said he felt he now had nothing to say. The talk really opened the eyes of astronomers.” And now, 24 years later, astronomers are using the laser guide star on the world’s biggest telescopes to find things like stars orbiting the Milky Way’s black hole. I have no idea what the Air Force is using it for.

Both the set-up for Jason and the boost to declassification of the laser guide star are quiet causes of long, long effects. Townes wasn’t even famous for doing them because he’d done so much more — I just this minute remembered he won a Nobel prize. But both are things anyone would be proud and grateful to have done. And how excellent, to be able to do so much with an administrative flick of the wrist, a few phone calls; and then go back to “the curiosity of how in the world this wonderful universe works,” as he said, “what’s out there and what’s it doing and how does it work and what makes it do such special things.”

____________

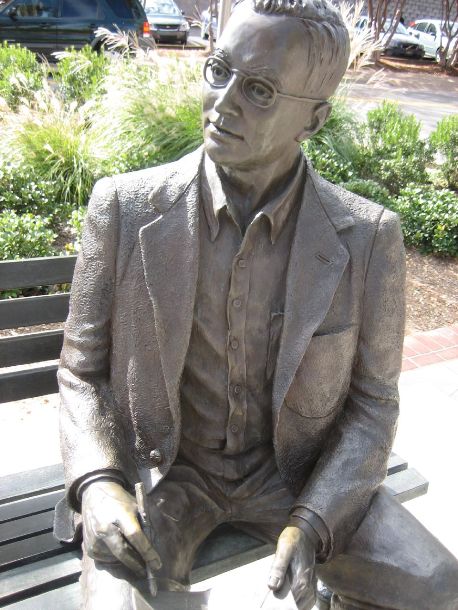

Photos: apologies for no photos of Townes, no good ones are available creative-commonly, but this is a statue showing the moment when, sitting on a park bench in Washington DC, he thought of the laser – Sarah; the European Southern Observatory using the sodiuim laser guide star – Y. Beletsky/ESO

One thought on “Charles Hard Townes Made Things Happen”

Comments are closed.