October 14, 2014: At a heady, expert-packed Ebola forum assembled at Johns Hopkins University, a Liberian man said more in a minute and half than everyone else said in five hours. He summed up the United States tainted history with Liberia and begged for respect, this time around.

October 14, 2014: At a heady, expert-packed Ebola forum assembled at Johns Hopkins University, a Liberian man said more in a minute and half than everyone else said in five hours. He summed up the United States tainted history with Liberia and begged for respect, this time around.

The expert forum was the best, yet. Top thinkers on the Ebola problem shared views and experiences; mapped the bioethics of green-lighting vaccines (getting approval to use them, provided people sign consent forms); talked about the bone-chilling exponential growth of this freak of nature, and how it could murder a million Africans by next year; and concluded that the global community is incapable of slowing its spread because of poor infrastructure.

Michael Osterholm, an outspoken biosecurity exert, called the World Health Organization’s response impotent, and questioned its future. “This outbreak is W.H.O.’s 9-11,” Osterholm said. “This will be a really very, very important time for reconsidering global health and how we respond to global health crises.”

At the end of many hair-raising presentations, this panel of all white men, but for one white woman, opened the microphones for questions.

That’s when Bobby Gborgar Joe spoke. He said, with a nervous laugh—filled with irony—that he had lost family to Ebola. “…So it’s personal to me when you have a conference like this without …asking people from the three countries who could have been included in this group, so that we don’t just hear European ideas about how to help the Black Man!” He drew in the microphone so that “Black Man” bellowed.

Hundreds in the audience applauded. Then came silence, an almost audible empathy. Participants and speakers got him; they agreed. Most had been on the ground in West Africa, or supported people on the ground.

He spoke again, with growing conviction, as if his dead countrymen sat on his back: “We have been with America since 1822,” he said, referring to the founders of his country—freed American slaves who sailed on schooners across the treacherous Atlantic to escape deadly racism in the U.S. South. They landed in West Africa and created the country of Liberia.

“You talk about infrastructure. We gave you the first airline to fight World War II,” he added, bringing up another important point, of how the United States used Liberia to wage war on Hitler. “The relationship has not been beneficial in a real turn,” he said, again drawing the microphone close to his mouth. “You want to sit around and talk about, oh, how much vaccine you can produce, and that’s good, but what about working with local herbalists who may know something…” He took a deep breath, visibly shaken, then decided to stop. “That’s all I want to say.”

The room applauded, again. He was right. A member of the panel had just described a Liberian village where local herbalists were asked to help western health educators contain Ebola, and it worked: people learned from trusted local leaders how to care for the dead and avoid contamination, and the spread stopped. It stopped! But where little coordination occurred, villagers fell prey to rumors—that white people brought them Ebola. Attempts by foreigners to educate them failed. And the disease spread.

It was all there, on the overheads, using graphs. The curves turned downward where villagers helped with containment. The curves turned upward—showing an exponential increase in case numbers—where westerners arrived in space suits, as if from another planet, to tell locals what to do.

A Kaiser study on how $1 billion will be spent to contain Ebola in the next six months shows that less than 5 percent will go to community outreach—asking local elders, like herbalists, to help stop the spread. Bobby Joe’s point was to ask: Really? That’s all? This is the one category of spending that will change conditions on the ground, and funding for it is last on the priority list?

His second point was equally poignant, but probably not as well appreciated. By bringing up World War II, he was trying to remind everyone that Liberia was a crucial partner to the United States in the fight against Hitler. He alluded to a little-known fact: that Liberia, in a significant way, contributed to the success at Normandy.

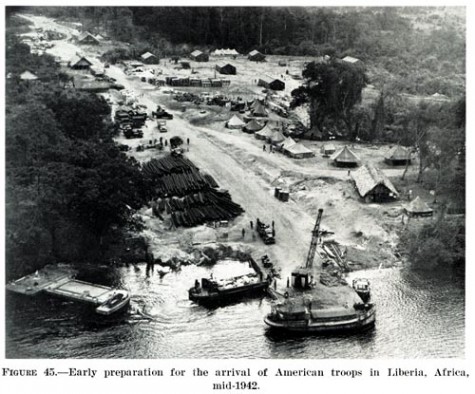

Before the Normandy invasion, Americans funneled troops and war supplies through Roberts Airport in Liberia, near Monrovia (“International” joined the title much later). The U.S. Army also used the coastal lagoon of Fisherman’s Lake for water-landing aircraft, and a small airstrip at Robertsport near the Firestone rubber plantation. All these areas are now among the hardest hit by Ebola.

Before the Normandy invasion, Americans funneled troops and war supplies through Roberts Airport in Liberia, near Monrovia (“International” joined the title much later). The U.S. Army also used the coastal lagoon of Fisherman’s Lake for water-landing aircraft, and a small airstrip at Robertsport near the Firestone rubber plantation. All these areas are now among the hardest hit by Ebola.

These ports provided the Allies safe, reliable transport for the enormous buildup of troops and supplies prior to the North African invasion, and for the capture of Tunisia, Sicily, and Italy. Liberia’s rubber plantations, meanwhile, put tires on Allied jeeps, trucks, aircraft, and other big machinery that rumbled through the Mediterranean to beat German forces.

These battles forced Hitler to keep troops in Italy instead of sending them where they were needed most: to fight Russia and to build a fortress along the Atlantic coast, to stop the Normandy invasion.

In Liberia, over 2,000 U.S. soldiers, mostly black, serviced airplanes loaded for the battles raging in the north. They guarded the rubber plantations from enemy attack. They ran mess halls and barracks for troops passing through from the United States. And they endured terrible malaria as they built runways and army camps.

Their presence triggered a massive migration of villagers from the interior, who came to these coastal ports for cash-paying jobs created by the needs of the U.S. military. Village men drained swamps, sprayed for mosquitoes, dug latrines, served food, did laundry, hung screens from barracks, and sat all night in palm trees looking for German U-boats.

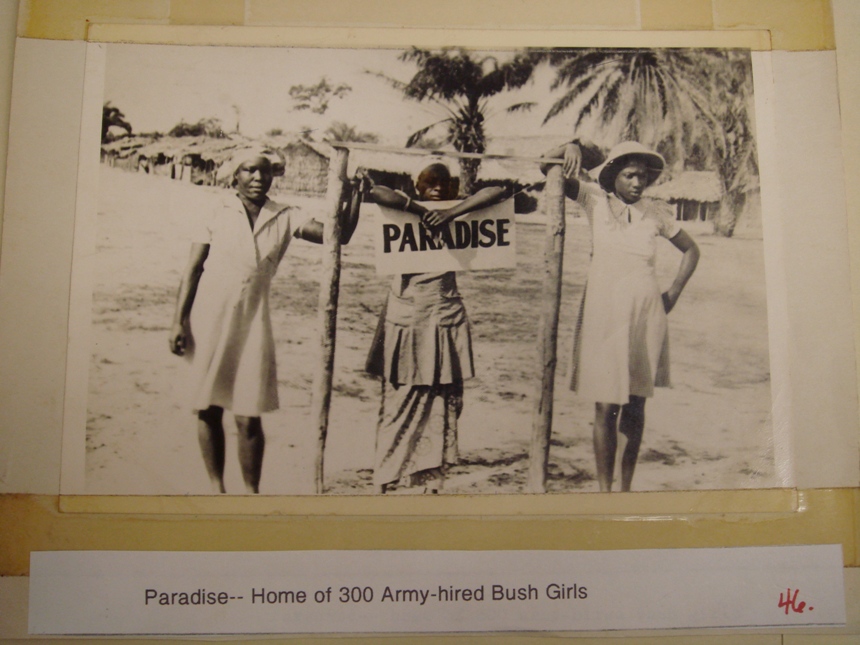

Several hundred Liberian women worked as prostitutes in three thatch-roofed camps set up to service U.S. soldiers—including one guarded by MPs to hold women infected with venereal disease (given to them by the Americans). Military doctors treated the women and when they were well allowed them back into the sex camps—which were called Shangri La and Paradise, each with 300 single-room huts for privacy, and open for business all day, but for the dinner hour.

Several hundred Liberian women worked as prostitutes in three thatch-roofed camps set up to service U.S. soldiers—including one guarded by MPs to hold women infected with venereal disease (given to them by the Americans). Military doctors treated the women and when they were well allowed them back into the sex camps—which were called Shangri La and Paradise, each with 300 single-room huts for privacy, and open for business all day, but for the dinner hour.

In exchange for using Bobby Joe’s country in this way, Liberian President Edwin Barclay was paid in kind: the U.S. Army examined thousands of village men for military service then trained them to fight. These newly minted Liberian forces protected Barclay from military factions that he believed were trying to overthrow him.

In exchange for using Bobby Joe’s country in this way, Liberian President Edwin Barclay was paid in kind: the U.S. Army examined thousands of village men for military service then trained them to fight. These newly minted Liberian forces protected Barclay from military factions that he believed were trying to overthrow him.

When the war ended, and American troops departed, they left behind guns, war machines, and a military mindset. Village life had broken down; family units had disintegrated (with men in armies and women in the sex trade). These were the seeds that grew into decades of violence, during which different armed military factions destroyed villages, raped women, and used machetes to dismember and terrorize the population.

Fast forward to the 2010s. Liberia is finally recovered from decades of violence. Villages have leadership and strong family units. Liberia’s economy is among the fastest-growing in the world. …Then Ebola strikes—through no fault of its own. A child in Guinea contracts it, maybe from a bat or bush meat. And Liberia falls.

Bobby Joe spoke from his bones. He spoke to this panel, but he was really speaking to U.S. policy makers, asking them to please respect his country at this harrowing hour, to work with his people and culture to help stop Ebola. Don’t step in again with a big foot and then leave. There’s no pill to make Ebola go away; it will come back. Use this opportunity to retool global health programming in a way that aligns international money with country health ministries so that the highest priority moving forward is to invest in local public health and other prevention- and education-based strategies.

Do that and, next time, local people will be competent enough to contain the disease—before it becomes a global emergency.

____________

Karen Masterson just published a book called The Malaria Project, a historical narrative about the U.S. government’s hunt for a malaria cure during World War II (NAL, Penguin, Oct. 2014). She teaches science writing at Johns Hopkins University and was a member of the Global Health Security team at the Stimson Center. She was awarded a Knight journalism fellowship in 2005 to study malaria at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Malaria Branch in Atlanta and with CDC investigators in Tanzania.

Karen Masterson just published a book called The Malaria Project, a historical narrative about the U.S. government’s hunt for a malaria cure during World War II (NAL, Penguin, Oct. 2014). She teaches science writing at Johns Hopkins University and was a member of the Global Health Security team at the Stimson Center. She was awarded a Knight journalism fellowship in 2005 to study malaria at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Malaria Branch in Atlanta and with CDC investigators in Tanzania.

____________

Photos: west Africa, from the XX Century Citizen’s Atlas, by Gabriel, via Flickr; Arrival of American troops — U.S. Army; Paradise prostitutes’ camp — courtesy of George and Katy Abramson Collection, Cornell University; Franklin D. Roosevelt and President Edwin Barclay of Liberia — U.S. National Archives and Records Administration

Is “arrrrrgh!” a comment?

I’m reading this a month later and unfortunately, I don’t hear Bobby Gborgar Joe’s word resonating in the news even today. We are quite the selfish bastards aren’t we.