Having grown up in Connecticut, I spent most of my childhood exploring streams, creeks, shorelines and marshes. Some of those places weren’t just mucky, they were dirty (as in “this is why we have the Clean Water Act” dirty). But all around, there were lush, green, magical places.

Having grown up in Connecticut, I spent most of my childhood exploring streams, creeks, shorelines and marshes. Some of those places weren’t just mucky, they were dirty (as in “this is why we have the Clean Water Act” dirty). But all around, there were lush, green, magical places.

When I moved to the arid Southwest, I couldn’t wait to plunge into the Rio Grande. As I kid, I’d envisioned a mighty river carrying Spanish galleons and tossing barges about.

So, um, yeah, it’s nothing like that.

I loved the Rio Grande anyway. I probably loved it more because it was unlike any river I’d ever seen. I loved its shallow, muddy waters and the maze of paths and game trails through the bosque. Even though the non-native Russian olive, salt cedar and Siberian elms heartily out-compete the cottonwood trees in many places, those riverside thickets are rich with songbirds and porcupines, coyotes and raptors.

More than 12 years ago, affection migrated into obsession when I was checking stream gages online (God bless the USGS!) and watching as the Rio Grande’s flows south of Albuquerque, New Mexico dipped as low as 14 cubic feet per second.

Water managers were supposed to be leaving some water in the river for the endangered Rio Grande Silvery Minnow, a fish that used to swim throughout the Rio Grande and the Pecos River. At the time, in 2002, the species only survived in a 173-mile stretch of the rio—a stretch that’s divided by dams and diversions into three sections.

When I questioned federal officials about the nearly waterless river, they assured me the gage was out of whack.

Then, when seven miles of the river dried up in early June 2002, they blamed the drought.

What really happened? At the start of irrigation season that year, so much water had been sucked into canals and ditches that the Rio Grande had changed from a flowing river into a sandy channel.

What really happened? At the start of irrigation season that year, so much water had been sucked into canals and ditches that the Rio Grande had changed from a flowing river into a sandy channel.

And it’s still happening. Last month, I wrote about how more than 20 miles of the Rio Grande had dried south of Albuquerque—even though we actually received decent monsoon rains this summer. Last year? About 30 miles dried. In 2012, more than 50 miles. And in southern New Mexico, about 200 miles are dusty for almost nine months out of the year.

For a dozen years, I’ve borne witness to how the politics of western water play out in its rivers. And I still haven’t learned how to harden my heart.

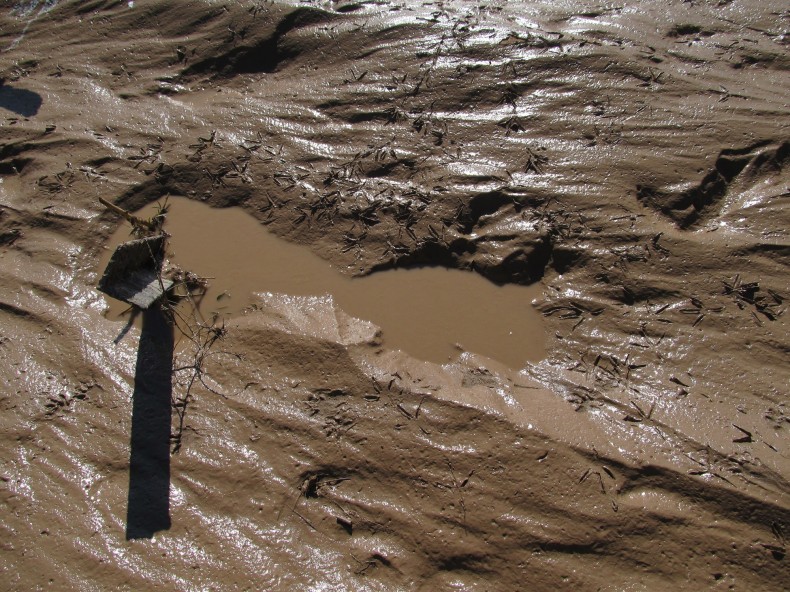

Traveling with biologists when they’re attempting to salvage the endangered minnows from pools, I’ve watched the sun warm the riverbed. The fish left behind – carp, mosquito fish, red shiners, and catfish – flicker and twitch even after the puddles have evaporated into thick mud.

I’ve watched sandhill cranes, ducks and crows fly off from the dry stretches once there’s nothing left to eat.

I’ve gone to the Rio Grande in summer and unsuccessfully searched for a spot deep enough to wade.

As an American journalist, I’m not supposed to advocate for one position or another, even when it comes to things like rivers running dry or species blinking out of existence. But really, my heart constricts with grief.

When I first moved to New Mexico in 1996, I came as an archaeologist. Excavating pithouses and campfire rings as someone new to the desert, I was only vaguely aware of the droughts and periods of scarcity ancient people had to weather.

During those six years in the field, I’d gape at the columns of rain hanging from the sky like tapestries. Unlike in New England, rain here doesn’t appear out of nowhere. It migrates across the sky, pushing ahead of it the scent of wet sage, creosote or greasewood. Before we figured out how to tap into aquifers and pump water from beneath the surface of the earth, those summer rains and winter snows determined where people would live—and if they’d survive.

Today in New Mexico, many Native people still live where their ancestors walked. Cliff dwellings, potsherds, and stone tool scatters mark the places people left thousands or hundreds of years ago. Some of those communities were lost to conquest and disease. Others relocated because of drought.

Today in New Mexico, many Native people still live where their ancestors walked. Cliff dwellings, potsherds, and stone tool scatters mark the places people left thousands or hundreds of years ago. Some of those communities were lost to conquest and disease. Others relocated because of drought.

Meanwhile, my culture is leaving behind “ghost rivers.” That is, rivers that flowed during the last century but have been sucked dry by cities and farms. The rivers that once graced cities like Phoenix, Tucson and Santa Fe no longer hold water most days out of the year.

I remember what it’s like to crouch and excavate what once were villages. Maybe that’s why I’ve decided to accept this obsession with a river that has sustained human life for thousands of years – and which deserves to keep running, even if it’s hard anymore to make it to the sea.

Laura Paskus is a reporter and producer who lives in Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Photos: (1) The Rio Grande north of Albuquerque, September 2014. (2) Drying puddles, July 2012. (3) The river near Mesilla, in southern New Mexico, January 2014. (4) In February 2014, a coyote dashes across the river as it flows through Albuquerque.

Well done and well said, Laura.

Ghost Rivers. Wow. This is amazing. Thank you for writing, and thank you for sharing.

Such an important and lyrical piece!