(Part 2 of 2; Part 1 appeared yesterday.)

Harry’s utterance “Damn damn Kepler on the Moon damn damn” immediately entered the lexicon of our little messenger world. I then introduced it to my non-work friends, who likewise adopted it as an absurdist catch-all. For years afterward my only knowledge of Kepler was as a punch line to a prank phone call. Only when I began researching astronomy for a book project, deep into adulthood, did I come to understand Johannes Kepler’s contributions to the history of science, including the three laws of planetary motion that provided the foundation for Newton’s universal law of gravitation.

Harry’s utterance “Damn damn Kepler on the Moon damn damn” immediately entered the lexicon of our little messenger world. I then introduced it to my non-work friends, who likewise adopted it as an absurdist catch-all. For years afterward my only knowledge of Kepler was as a punch line to a prank phone call. Only when I began researching astronomy for a book project, deep into adulthood, did I come to understand Johannes Kepler’s contributions to the history of science, including the three laws of planetary motion that provided the foundation for Newton’s universal law of gravitation.

Even then, however, I remained ignorant of Kepler’s contribution to the history of literature: He was the author of the first work of science fiction.

A year ago a student in the Science as Narrative course I teach first brought Kepler’s Somnium to my attention. I’m teaching that course again this semester, and in the past few weeks we’ve been discussing Kepler. This time I looked up Somnium online, and what I found was a truly transgressive work of literature. Also, the evidence in Harry’s favor.

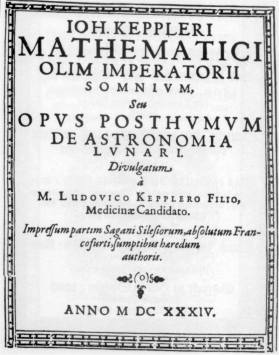

Kepler wrote Somnium (Dream) in 1608 (though it wasn’t published until the 1630s, several years after his death). For historical context, remember that Copernicus’s cosmology relying on a Sun-centered universe was just over 60 years old. In the absence of empirical evidence, however, the Church could regard heliocentrism purely as a mathematical exercise; not until 1609 did Galileo begin to gather that evidence with the help of a new invention, the telescope. Still, in 1608, you couldn’t be too careful, and Kepler was quadruply so, at least.

His short book opens with a narrator, who might or might not be the author, recounting a dream. In the dream, the narrator is reading a book. In the book, the main character hears a tale. The tale unfolds entirely in the words of the daemon, or alien, who’s telling it.

Some of the tale is fantasy: Daemons regularly transport people from Volva (read: Earth) to Levania (Moon), which is populated with creatures and vegetation. Some of the tale is science: Kepler, who had spent years as an astronomer working with the instruments and records of Tycho Brahe, the greatest astronomer of the immediately pre-telescopic era, includes lengthy explanations of what the duration of day and night, the appearance of eclipses, and the positions of planets and constellations would be to an observer on Levania. And all of the book is deeply subversive, because of that specific perspective: the point of view of an observer on Levania.

In the Copernican system, the Earth is merely one more “wanderer”—the meaning of the Greek word planētē. The point of view of someone on Earth is no more privileged than that of an observer anywhere else in the universe. “Because the stars are moving,” the daemon tells the main character of the book within the dream of a narrator who might or might not be Johannes Kepler, “Levania seems to stand no less motionless to its inhabitants than our Earth to us.” In short, if you lived on the Moon, you’d think you were at the center of the universe.

I’m not suggesting that Harry was familiar with Somnium. I’m not suggesting he was familiar with Kepler’s three laws. I’m not even sure he was familiar with the Moon, at least by the time we teenagers got around to tormenting him. But I do know this: All along the joke was on us.

Damn damn.

Thanks, Richard, for calling attention to Johannes Kepler who, IMHO, is the most interesting person who’s ever lived(!). Not only was he marvelous theorist, but the events of his life are almost beyond belief. Plus, he was a marvelous writer. Here’s an excerpt from the preface of the 5th Book of his Harmonice Mundi. “….Having perceived the first glimmer of dawn 18 months ago, the light of day 3 months ago, but only a few days ago the plain sun of a wonderful vision–nothing shall now hold me back. Yes, I give myself up to holy raving. I mockingly defy all mortals with this open confession:I have robbed the golden vessels of the Egyptians to make out of them a tabernacle for my God, far from the frontiers of Egypt. If you forgive me, I shall rejoice. If you are angry, I shall bear it. Behold, I have cast the dice, and I am writing a book either for my contemporaries, or for posterity. It is all the same to me. It may wait 100 years for a reader, since God has also waited six thousand years for a witness…” Ref: Arthur Koestler’s “The Sleepwalkers”, Part Four “Chaos and Harmony”.

I highly recommend Koestler’s book!