There are a lot of ways to follow the progress of the Curiosity rover as it probes the geological history of Mars. But you could do worse than following one of her drivers, Scott Maxwell, on twitter (@marsroverdriver). Sure, his tweeted celebration of Curiosity’s successful touchdown late Sunday night — “Hey, I still have a job Monday. : D” is a long way from “One small step for a man…” But it’s eloquence of another kind — immediate, funny, and as playfully enthusiastic as a Labrador puppy with a new ball.

There are a lot of ways to follow the progress of the Curiosity rover as it probes the geological history of Mars. But you could do worse than following one of her drivers, Scott Maxwell, on twitter (@marsroverdriver). Sure, his tweeted celebration of Curiosity’s successful touchdown late Sunday night — “Hey, I still have a job Monday. : D” is a long way from “One small step for a man…” But it’s eloquence of another kind — immediate, funny, and as playfully enthusiastic as a Labrador puppy with a new ball.

During the cold war, we had fighter pilot astronauts. In today’s networked, virtualized world, maybe it’s fitting that our front-line space explorers are Earth-bound joystick jockeys instead. Whatever might be missing in terms of square-jawed swagger is more than compensated for by a knack for humor and emotional presence not often associated with the rocket men of old.

I emailed and tweeted with Maxwell for a story earlier this year, not about the adventures to come with the new probe, but about life at the controls of the previous two. As the Curiosity teams go about testing their systems and preparing to roll out across the Martian surface, it seems like a good time to cast an eye back to some of the successes and heartbreaks of the Mars Exploration Rover (MER) mission, with the rovers Spirit and Opportunity.

I asked Maxwell about high points at the controls of the Mars rovers. Here’s what he had to say, very slightly edited for clarity:

“The MER project has been like a slot machine that won’t stop paying off. We put in our quarter, pulled the lever, and money started tumbling out — and tumbling out, and tumbling out, and tumbling out. Thanks to that, I can hardly answer your question in any finite amount of space; there’s just too much. But here are a couple of anecdotes.:

On the Spirit side of the planet, I don’t think I’ll ever forget the first time I drove her. It was just a few meters along a simple path — we wouldn’t even bother to yawn at it today — but it was magic to me then, as it’s magic to me now. I went home and should have slept, but all I could do was stare at the ceiling, in awe that right then, on Mars, there was a robot doing what I told it to do. It was dead amazing, and that feeling has never left me and I hope it never will.

On the Opportunity side of the planet, we always talk about how Mars keeps bringing us new missions. Opportunity keeps reaching new destinations — Eagle Crater (where she landed), her own heat shield, the dune fields, Victoria Crater, and now the Manhattan-sized Endeavour Crater — each of which is like a whole brand-new mission when we get there, offering new geology and a new chance to explore deeper and deeper into the Martian past.

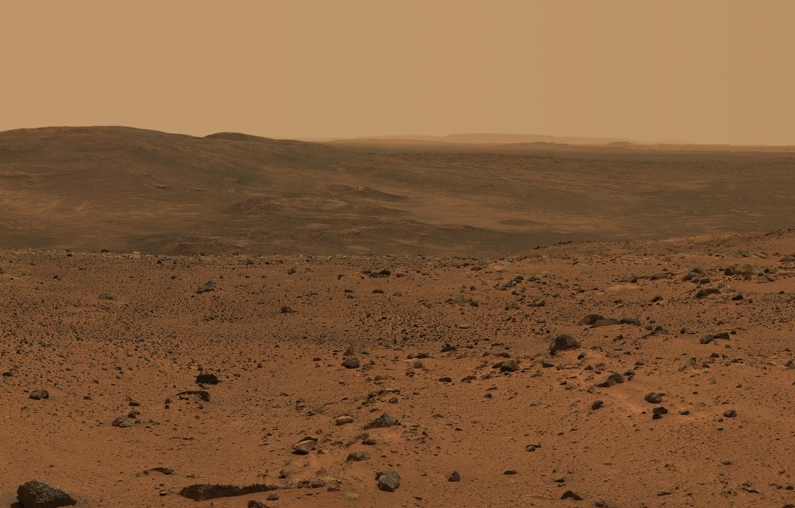

But possibly the high point of the entire mission for me is Spirit‘s conquering of Husband Hill. She fought and struggled every centimeter up that Statue of Liberty-sized mountain — a struggle she had to go through in order to find the Martian water evidence she came to the red planet for. The gorgeous color panorama she took from atop that hill is beautiful and amazing in its own right, but also because of what it says to me about the value of simple, dogged persistence. Spirit never gave up, and we never gave up on her, and by god, we did what we set our minds to. She was amazing.”

I also asked about disappointments, and the experience of losing the Spirit rover, which finally died when its solar panels could no longer charge the batteries in the deep of Martian winter, after the rover had been stuck in soft soil for months:

“The most disappointing and frustrating moment had to be losing Spirit — we were so close; we had figured it out; another couple of weeks would have done it. It’s frustrating partly because I feel we acted reasonably at every turn — we played the game properly, we just lost. *Damn* it.

When we realized Spirit was dangerously bogged down, we immediately retreated to our testbed facility, where we have a high-fidelity copy of the real rovers that we can safely experiment with. At least we had the luxury of time: the dangerous Martian winter was months away, and we intended to spend the intervening time well. We spent months working out techniques for moving Spirit again — none of them very promising, as it turned out, but we had reason to hope.

Spirit’s predicament was very serious; since one of her six wheels had failed, we had five working wheels and one anchor, and we were trying to drag ourselves out of some unfairly slippery stuff. So we tested and tested, got our ducks in a row, and held a NASA-level review. They gave us the green light. Now it was all up to us. We started using those techniques on Mars, and initially we were very happy; Spirit was behaving spot on predicts. We didn’t have a lot of spare time any more, but we were making progress and were confident we’d escape. Then a second wheel failed. That was just about the only thing that could possibly have made our situation worse.

Now, instead of five wheels and one anchor, we had four wheels and two anchors — and instead of having lots of time to play with, we had to fly by the seat of our pants. We listed everything we could think of that might work, and started trying stuff — on Mars, this time; there was no time to try things in the testbed first. What worked for us, we discovered, was to “swim” our way out. We could steer the front and back wheels out, and they’d act on the soil we were buried in like flippers do in water, pushing Spirit backward just a little bit. Then we’d spin the wheels a while to build up another pile of material, push back a little farther, and so on.

As crazy as it sounds, this was working! We were making progress! We just couldn’t make progress fast enough. Another couple of weeks and we’d have been out — but we didn’t have that time. Winter stopped us, and Spirit went into deep hibernation in a desperate last-ditch effort to survive. As far as we can tell, she never woke up again. *Damn* it.”

Finally, I asked about how close the experience of driving the rovers actually took the operators to the surface of Mars. And came to appreciate that the experience might be remote, but that doesn’t mean it’s not more visceral than virtual:

“I grew up dreaming of space exploration. The only thing better than going there virtually in our robot bodies would be going there physically in our squishy frail human bodies. If they’d send me, I’d go — I wouldn’t even have to think about it. I’d be on the rocket tonight if there were one leaving. I hope NASA can get its act together and send that rocket — I *want* it.

I think the first thing you’d notice on Mars is how light you felt despite your spacesuit. Gravity’s only about a third of Earth’s, so divide your weight by three and imagine feeling that light forever. Visually, it’s a weird place — a frozen, airless, waterless, cratered moonscape. And it’s intensely lonely — other than a single robot, there’s nothing moving on the surface of a world that has about the same surface area as all Earth’s continents with no pesky oceans. Inside your spacesuit, then, it would be kind of like scuba diving through an endless Utah desert.”

***

Image: detail of the Spirit rover’s panorama from atop Husband Hill, NASA.

2 thoughts on “SCUBA Diving through the Endless Martian Desert”

Comments are closed.