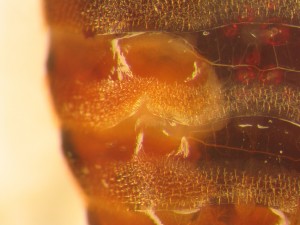

Behold the bed bug penis. Entomologists call it a lanceolate paramere, where lanceolate means “shaped like a lance head” and paramere, the “copulatory hooks formed from outer subdivision of primary phallic lobes.” Put more simply, it curves out from the tip of the male’s abdomen and ends in a wicked point, like a dagger.

This shape is no coincidence. The bed bug penis is adapted to stab.

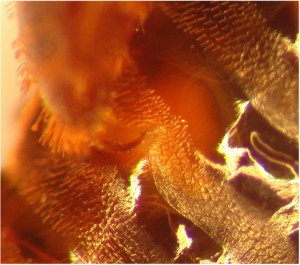

The male bed bug—and we’re talking the common bed bug, Cimex lectularius, the species you’ve likely read about in the news, although all 100 or so related species perform a similar feat—climbs onto his lover’s back, his head draped casually over the equivalent of her left shoulder and his body curved around hers in a violent embrace.

He next aims his pointy member not at her genitals, the target choice of more reasonable animals, but at the right side her abdomen. There, he stabs her, ejaculating directly into her body cavity.

Scientists call this traumatic insemination. I call it rude. Isabella Rossellini calls it art.

Just watch.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MakIB_IJnu0

(As a former fact checker, I would like to note an error in the film. Female bed bugs don’t lay 500 eggs in two weeks. The correct number is between one and a dozen per day, or up to 500 in a lifetime. Also: bed bugs do not wear unitards. Facts. Checked. Moving on.)

To counteract the male’s stabs, the female bed bug has developed her own unique organ, the spermalege. Outside the body, the spermalege appears as a small notch on the right side of the female’s segmented abdomen. Inside, a mass of immune cells protects her from bacteria that coat the male’s paramere and helps heal her love wounds.

The male aims for the notch and stabs into the mass of cells; the sperm, which also has anti-microbial properties that may shield it from bacteria or help further protect the female, then travels into the female’s circulatory system, ultimately ending up in bags attached to her ovaries. The female stores the sperm in these handy bags, using just a bit at a time to stretch her fertilization period to between five and six weeks.

Bed bugs perform this strange lovemaking ritual despite the fact that the female appears to have fully functional genitals. Let me repeat that. The male bed bug bypasses a perfectly good set of genitals, choosing instead to stab his lady in the belly with his dagger penis.

What the hell? Is probably what you’re thinking. It’s a good question, and one that entomologists have been asking for nearly a century. The answer may lie in an evolutionary biology concept called sexual conflict, where the male of a species evolves features that increase its chances of breeding, but at the female’s expense. The reverse may also happen. Their partners coevolve strategies to either fend off unwanted advances or to protect themselves from physical harm in a so-called sexual arms race.

It isn’t entirely clear why bed bugs evolved their version of sexual conflict, but the strongest hypothesis relates to the mechanics of the female’s sperm bags. The last sperm in is the first to make it to the ovaries; the last male to mate with a female, then, gets to cut the paternity line. This may help explain why each male mates with such frequency—between 20 to 25 times the amount necessary for the female to produce the maximum number of eggs.

In conclusion, I wrote you a limerick, which is perhaps the best literary genre with which to convey the bed bug’s mating style:

The bed bug traumatic’ly inseminates

Much to the dismay of his many mates

Not one for romance

He stabs with his lance

No surprise he’s not asked out on many dates

**

Brooke Borel is writing a book about bed bugs for the University of Chicago Press. For more bizarre tales of the bed bug, as well as other sciencey stories, follow her on Twitter @brookeborel.

Additional Sources:

Interview with Richard Naylor, Sheffield University

Jacques Carayon, “Traumatic Insemination and the Paragenital System,” in Monograph of Cimicidae by Robert Usinger (College Park, Maryland: The Thomas Say Foundation, 1966; Reprint Entomological Society of America, 2010), 1-9.

Margie Pflester, Philip Koehler and Roberto Pereira, “Sexual Conflict to the Extreme: Traumatic Insemination in Bed Bugs,” American Entomologist, Winter 2009, 244-249

Michael Siva-Jothy, “Trauma, disease and collateral damage: conflict in cimicids,” Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 361(2006): 269-275

Image Credits:

I did some research for a TV doco years ago which included some work on bed bugs. This is a fabulous story.

actual number of eggs laid on average.. about 2.5 per day… but not every day!!

about 300-400 in a lifetime.. under the most ideal conditions.

500 is a “stretch……..”

Hi Sam: Yes, it’s true that they don’t lay eggs every day (thankfully!). Only after the female has mated, and only under the right conditions (food availability plays a role here, for example). The 500 number is the upper limit that I’ve seen in the scientific literature, which is why I said “up to 500,” but yes, on average it is closer to the range you state.