“Mommy, why did you kill me?” was the first line of the comment. It devolved from there into a maudlin, hallucinatory, and occasionally Freudian fantasy of an aborted child’s final message to his mother, and it ended with the little guy playing baseball with God in heaven while the mother burned in hell.

“Mommy, why did you kill me?” was the first line of the comment. It devolved from there into a maudlin, hallucinatory, and occasionally Freudian fantasy of an aborted child’s final message to his mother, and it ended with the little guy playing baseball with God in heaven while the mother burned in hell.

The reply was brief and furious: “If men could get pregnant, abortion would be a sacrament.”

Another joined in: “When a man can get pregnant, I’ll be happy to listen to his opinions about abortion.”

The abortion flamewar I’m describing took place in 1999, and it had the honor of being my first. It was quite an education. Unfortunately, the dialogue hasn’t advanced much in the last 13 years, either on messageboards or in real life.

Anonymous Internet Person #2 was right: men can’t get pregnant. But will women always have to bear the sole responsibility and consequences for reproductive decisions that two people made? Perhaps not. Technology advances may soon allow men and women to approach parenthood from a similar perspective, by separating the act of ending a pregnancy from the act of ending the developing fetus’ life. The concept they enable is called ectogenesis, or gestation outside the womb. Not only would ectogenesis completely reframe the long-ossified abortion debate, it could also help women who have trouble carrying their own child to term, giving them an option beyond surrogacy. In the future, ectogenesis might even give indecisive women like Cassie and me the choice of offloading our pregnancy onto our male partners. But is the external uterus an inevitable reality or a fairy tale?

In 1997, a pro-life group called Nightlight Adoptions set up a program called Snowflakes. It brokered the surplus frozen embryos generated during fertility treatments, which would otherwise be discarded or donated to science, and offered them to pro-life people for adoption. To adopt the snowflake, a woman could simply implant that embryo, become pregnant, and bring the baby to term. Embryo adoption wasn’t only for people of the pro-life persuasion, and it ended up being not so simple, but it was the first example of a pro-life critique with a concrete solution.

If only there were some way to extend the concept, transplanting a developing fetus from a woman who found herself accidentally pregnant.

But a straight-up fetus transplant is just not in the cards, says Claus Andersen, a reproductive physiology professor at Copenhagen University Hospital, and here’s why. From the moment the blastocyst implants into the mother’s uterine lining, it is on her life-support system. At that point, removing the embryo becomes roughly on par, in complexity, with removing an egg from cake batter. To transplant it, you would need to move all the support systems too: the growing amniotic sac, the placenta, and probably some of the uterus too. The mother might become sterile, and the fetus would probably die.

And even if it were possible to transplant this entire delicate ecosystem into a new host, the next problem is immediately apparent. Like any organ, a transplanted uterus (and the attendant embryo) would likely be summarily rejected.

But this apparent dead end does leave one intriguing loophole: scoop up the blastocyst before implantation. This is possible during the 7- to 10-day window after the sperm has joined with the egg, and the blastocyst is still a free agent, rolling down the Fallopian tube to the uterus. Snap it up then, and you avoid getting the mother’s system involved.

But if the mother’s system isn’t yet involved, how would you know conception had happened? During its journey, the blastocyst emits a signal to alert the uterus to get ready for a pregnancy. This hormone, human chorionic gonadotropin, is already detected by ultra-sensitive pregnancy tests that can identify a pregnancy several days before you even miss your period.

Make the hCG assays a little more sensitive, Andersen says, and you’d have a way of knowing the egg has been fertilized, which would give you a chance to catch the embryo before it implants. Granted, that leaves the problem of locating the blastocyst, which at this point in its development is 0.1 millimeters around and invisible to the human eye.

But let’s assume you can find it and extract it: then what?

You could vitrify the embryo, or flash-freeze it, the way IVF procedures do now. That way it can be stored without problems for at least five years. It could then be adopted. Or, if the technology matures sufficiently, the embryo could be implanted into an artificial uterus.

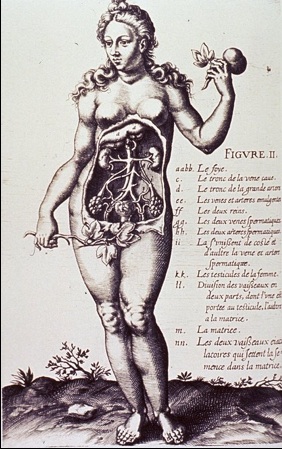

Brave new world. Literally. In Aldous Huxley’s vision of the dystopian future, all babies are “decanted” from artificial wombs. He wasn’t the first proponent of the external uterus; the technology has been hotly anticipated since the 1600s. In the 1920s, external baby incubators were thought to be were just around the corner, and the term “ectogenesis” was coined.

Brave new world. Literally. In Aldous Huxley’s vision of the dystopian future, all babies are “decanted” from artificial wombs. He wasn’t the first proponent of the external uterus; the technology has been hotly anticipated since the 1600s. In the 1920s, external baby incubators were thought to be were just around the corner, and the term “ectogenesis” was coined.

The actual science, however, remained largely theoretical until the late 1990s, when, in a much-publicized Japanese experiment, Yoshinori Kuwabara of Juntendo University successfully sustained a fetal goat in an artificial womb for a few days. He and his team had removed the fetus from its mother after four months of normal gestation, connected its umbilical cord to tubes and an artificial placenta in an artificial uterus, and let it finish out its gestation. Kuwabara, who has since passed away, was on record as saying he hoped his technology would soon be advanced enough to support a human fetus.

But the chances of that are slim, Andersen says. “If we knew how to take a developing child out of the womb in the second or even early third trimester and successfully grow it in an external uterus, we would be doing it right now,” he says. There are so many premature births rights now that if we had any idea how to make it happen, someone would be making a lot of money off the technology. But it’s too complicated: Kuwabara’s goats were born with deformities.

But what if you took the opposite approach, creating an artificial uterus that, like nature’s version, grows around a newly implanted blastocyst? Hung-Ching Liu, a fertility researcher at Cornell University, demonstrated success doing just that. She and her team grew an artificial uterus from donated uterine lining cells. Liu successfully got mouse as well as human embryos (donated from IVF procedures) to implant into the uterus. According to regulations, you can’t experiment with human embryos older than 14 days, so these studies had to be stopped. However, the mouse trials were promising. Still, after a flurry of research in the mid-2000s, research on the artificial uterus seemed to fall off a cliff.

Recently, however, it has been quietly gaining ground again. After Liu’s work, the science has become more focused on mimicking the uterine environment either by manipulating living tissue or with engineered materials. In 2010, for example, researchers at Tufts University grew an artificial cervix using spider silk. In a 2009 study, Chinese researchers constructed an artificial womb out of several layers of real uterine tissue, and concluded that it could support the development of an embryo. The following year, German researchers reported progress in blood vessel growth in engineered tissue, including the kind suitable to create an artificial uterus. If the technology advances sufficiently, it might even be possible someday to implant such an artificial uterus in a man.

In the wake of this research, ethicists and legal scholars have jumped into the fray. Some think these recent technological advances mean ectogenesis is right around the corner. Others insist that it is merely a biologically impossible but convenient fantasy.

After all, the promise of the artificial uterus is seductive: ectogenesis would put men and women on the same moral ground when deciding the fate of a developing (or frozen) embryo, free to regard it from the same abstract perspective. One frequent complaint from men’s rights groups is that a woman can decide to keep a man’s child and legally force him to pay for 18 years to support that child—he has no way of “terminating” a pregnancy if his partner does not consent. On the other hand, some men say they have been traumatized by a woman’s decision to abort a child that was not strictly her own. Removing a pregnancy from one partner’s body would take the choice and responsibility away from one and give it to both.

But in solving one ethical dilemma, ectogenesis would pose ten more. How long could you put off reviving a frozen pregnancy? And if you choose instead to implant it into an artificial uterus, what happens to the unwanted child after he or she has been born? Does he or she go straight to an orphanage? If neither parent wished to be involved in the child’s life, the state might get involved, requiring them to pay child support to ensure their offspring has a decent quality of life.

I don’t know which will happen first, an external womb designed so that no one has to be pregnant, or an artificial womb designed so that anyone can get pregnant. But from years of tech reporting I can say one thing: if the desire for a technology is there, someone will make it happen. There are a lot of ethical minefields to clear, but ectogenesis comes with an irresistible hook: this technology would bring us closer to the day when motherhood and fatherhood mean the same thing.

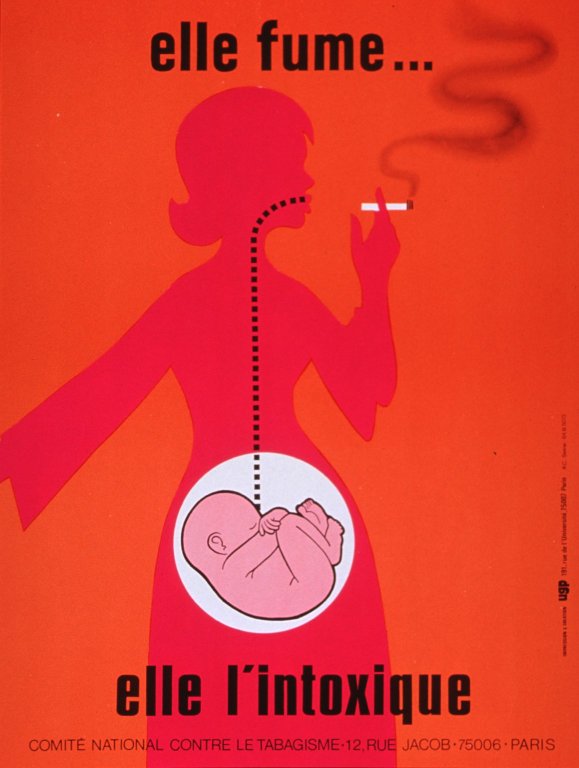

Image credits: Images from the History of Medicine

My only concern is that when this does happen, will we become so dependent on artificial gestation that we will evolve to the point of no longer being able to have children without technology?

Hi Magoonski,

I doubt it very much. On the whole, most women will still want to experience biological motherhood. Plus it will be easier and cheaper. I think the artificial womb will be for women who can’t carry their own children and don’t wish to employ a surrogate, or for women who are opposed to abortion, or for — in the long, long term future — men who wish to conceive without a female partner.

Sally

My only comment is that I am not sure why my previous comment wasn’t accepted.

“But will women always have to bear the sole responsibility and consequences for reproductive decisions that two people made?”

This is arguably a false statement. Men do bear some, albeit less, responsibility for the reproductive choices that they and their partners make.

Men are required to provide child support for their progeny, whether or not they wished to produce them. Further, they may be required to provide child support for children they are presumed to have fathered even if later evidence indicates that they are not the biological parent.

In states where the law favors easier abortion access, men arguably have greater responsibility relative to their available choices. A woman may choose whether or not to carry a child to term. This seems fair given that she is subject to the consequences of pregnancy or abortion. As the law stands today, a man has no right to relinquish parenting rights and responsibilities to a child that he didn’t wish to have. In an era when abortion access was limited and women’s professional options were limited, this seems just. However, in modern times (at least in left-leaning states), this is no longer the case. Further, since a woman likely knows her menstrual cycle and birth control habits (OCP/IUD use, etc.) better than her partner does, she has superior a priori knowledge whether sex will result in conception. Thus, a man may be required to support a child he didn’t want and was told (in good faith or not) was not likely to be conceieved. This asymmetry of control and responsibility seems unfair. The consequences of pregnancy are greater for women and therefor they should full control over choices that effect their health and well-being. However, men should not have to provide for children they did not wish and that their partners chose to keep.

Before Sally’s posting I had composed a comment in which I reflected that while the previous blogs were all vigorous and pithy and emotive they lacked one essential thing, a man’s point of view.

I said that because when people ask me what I regret in my life. The one thing I always say is: I never had a child. And they say but you have children. And I say, I do, and I love them, and I helped raise them, and I feel their love for me but I didn’t really have them. That’s what their mothers did. And there is no real way for me as a man to cross from drip of sperm procreation to the tidal wave of birth.

Men in a biological sense are, to quote a friend, more like guarantors on a house loan than true house builders.

The previous essays – I use that literary expression and not the word blog because it seems to me they are more literally like the French essayer, that is “to try, to attempt” an argument –were fundamentally existential. Motherhood wasn’t anyone’s biological destiny; it was a decision. Do I have a child or not? Do I have one, or two, or more? How do I integrate a child with my other me’s? The writer me? The wife me? The simply human me?

Sally’s essay went far beyond that, but left me wondering two things. The first is exactly what kind of feelings some/many/most women will have about themselves if men begin having children without them. Will it be a sense that we humans all now are equal, or will it be a sense that science/technology has defiled our intrinsic sexual inequalities? Not to mention cat/dog/tyrannosaurs rex fights over the difference between “natural” versus “artificially” created children.

But what I really wonder about is if it is ever gone to happen. Sally says if we want something enough, technology a la a Jean-Luc Picard command will make it so. I would suggest this is wish hubris in the extreme. What we have done in the modern world with our technology has been amazing. But what we want – time travel; immortality without aging; the ability to explore the universe with ease – is beyond amazing. I would suggest that those things are quite likely to remain outside human’s powers to ever do, and if so, wanting them is the same as having fallen in love with a magician’s illusions.

@Stephen Strauss: Your comment wasn’t rejected, it just hadn’t been accepted yet; Sally is in some extremely weird time zone, really. And when the two male LWONites were asked if they wanted to make this a Parenthood series, they ducked. Tom said something like, he’d learned that when women start talking about what to do with their bodies, he’d learned to feign interest in wrestling. But never fear, because we’ve vowed that the mens’ point of view shall, in the nearish future, be represented.