If you were sitting in front of a computer in China right now, you wouldn’t be reading this. Nor would you have seen Cameron’s post about a snail invasion on Monday or Michelle’s piece yesterday on a poem inspired by Marie Curie. In fact, when you tried to open our website, your computer would have heaved and roiled and finally timed out. After several tries, you would have likely concluded that we had server problems and eventually crossed us off your list.

If you were sitting in front of a computer in China right now, you wouldn’t be reading this. Nor would you have seen Cameron’s post about a snail invasion on Monday or Michelle’s piece yesterday on a poem inspired by Marie Curie. In fact, when you tried to open our website, your computer would have heaved and roiled and finally timed out. After several tries, you would have likely concluded that we had server problems and eventually crossed us off your list.

That’s exactly what the government of China wanted. Currently, the Last Word on Nothing.com is persona non grata in China, blocked from its millions of computers. The country’s Great Firewall—the massive internet censorship operation masterminded by the Ministry of Public Security in Beijing—has risen up against us and struck our website down.

I stumbled upon this fact by chance. An old friend of mine is teaching at a Chinese university this semester, and he often emails about the things that catch his eye there. Like many western researchers, he is accustomed to staying on top of science and cultural news by cruising the web. But China’s great firewall makes this extremely difficult. Over the past three months, he has been unable to log on to YouTube, Facebook, or Twitter. Google Books, he says, isn’t doing very well; Google Maps is patchy at best.

What irritated him the most this week, however, was that he couldn’t read his favorite blogs on blogspot.com, a service owned by Google. They were all blocked, he wrote. And that observation got me thinking about our site. We aren’t on blogspot.com—we’re hosted at a private server. But could we be censored, too?

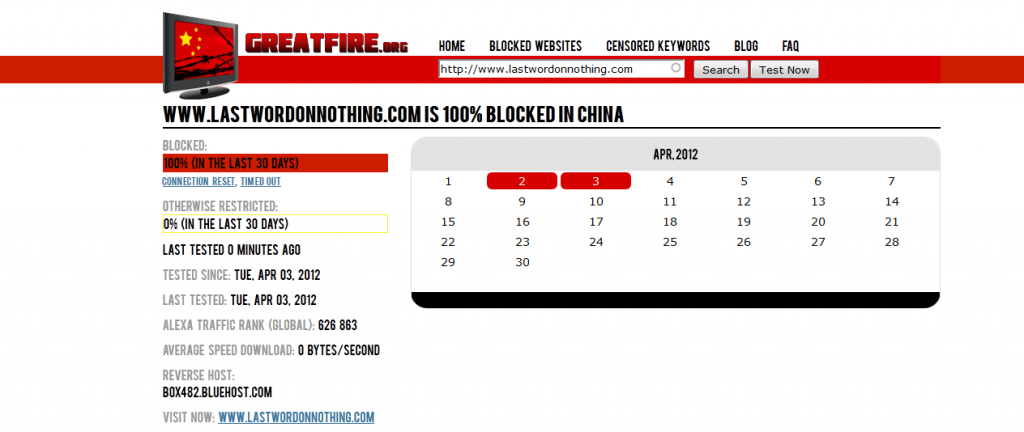

It seemed really unlikely, but I decided to check anyway. My first stop was Greatfire.org, which investigates internet censorship in China. Greatfire offers a free service, testing web addresses to see whether or not they are blocked in China. So earlier this week, I checked www.lastwordonnothing.com. I was gobsmacked by the result: on both April 2 and 3, we were blocked. Not just restricted. 100% Blocked.

It seemed really unlikely, but I decided to check anyway. My first stop was Greatfire.org, which investigates internet censorship in China. Greatfire offers a free service, testing web addresses to see whether or not they are blocked in China. So earlier this week, I checked www.lastwordonnothing.com. I was gobsmacked by the result: on both April 2 and 3, we were blocked. Not just restricted. 100% Blocked.

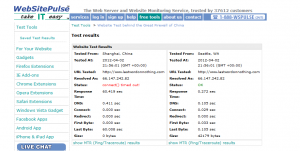

I still needed convincing, though. It didn’t seem possible or real. So I checked out two other testing websites. One of them, WebSitePulse, supplied detailed comparative data. As you’ll see in the screenshots to the left (and please click on them to get a better look), computers in Munich and Brisbane easily opened LWON. The Beijing computer, however, couldn’t connect at all, while the Shanghai computer labored mightily and then timed out. Chinese censors, I’ve since learned, regularly manipulate the loading time of blocked websites, so the user thinks there’s a server problem. Greatfire, for example, categorizes a “timed out” message as censorship if it fulfils two conditions: if the web request takes less than 15 seconds when accessed from the United States, and more than 15 seconds when accessed from China. As you’ll see in the screenshots, our request took 0.272 seconds in Seattle and 60.419 seconds Shanghai.

I immediately wanted to know when the censors in Beijing began dogging us. That’s difficult to tell. Greatfire, for example, only supplies information from the time of registration–in our case, since April 2nd. But if I had to guess, I’d say it’s been going on a while. The little red-dot map that you see on our home page collects info on where all our visitors come from. (Click on it and you’ll see what I mean.) Since October 19, LWON has had just 9 visitors from China—with all its western tourists, ex-pats and students, and its estimated 1.3 billion citizens, a growing number of whom now speak English. Compare that to India. We’ve had 2504 visitors from there.

I immediately wanted to know when the censors in Beijing began dogging us. That’s difficult to tell. Greatfire, for example, only supplies information from the time of registration–in our case, since April 2nd. But if I had to guess, I’d say it’s been going on a while. The little red-dot map that you see on our home page collects info on where all our visitors come from. (Click on it and you’ll see what I mean.) Since October 19, LWON has had just 9 visitors from China—with all its western tourists, ex-pats and students, and its estimated 1.3 billion citizens, a growing number of whom now speak English. Compare that to India. We’ve had 2504 visitors from there.

What I’d most like to know, however, is why Chinese censors consigned our site to oblivion. At first, I thought they could have been targeting science-related sites, so I ran the web addresses of Nature, Science, Scientific American, Discover and New Scientist through Greatfire. Beijing had blocked only one of these—www.nature.com—and that for just two days over the past 11 months: October 15, 2011 and September 27, 2011. Out of curiosity, I quickly scanned its news archives for those dates to see what was happening. But nothing stuck out as particularly China-unfriendly.

So I am mystified. How did LWON catch the eye of the censors in Beijing? When I asked my old friend in China, he wrote back right away. Blogs, he wrote, are forums for free speech and opinion, and “they cannot and will not be tolerated in China.” That comes from a Sinologist who has studied China for more than 30 years.

I feel miserable when I think of all those keen young Chinese students who want to know what’s going on in the world, who want to hear what others think, who want to check out YouTube videos or tweet to their friends, or even, heaven forbid, very occasionally drop into LWON to see what’s up. Who would have thought posts on Mr. Cosmology or Christie’s counting compulsion could seem so threatening?

I feel miserable when I think of all those keen young Chinese students who want to know what’s going on in the world, who want to hear what others think, who want to check out YouTube videos or tweet to their friends, or even, heaven forbid, very occasionally drop into LWON to see what’s up. Who would have thought posts on Mr. Cosmology or Christie’s counting compulsion could seem so threatening?

Censorship is an evil that strikes at the very heart of human conversation. It begins at Tiananmen Square, and if left to grow unchecked, its tentacled grip ends up far, far away, at a place like this.

Screen shots courtesy greatfire.org and websitepulse.com. Please click to enlarge the images. Map of internet black holes, courtesy Wikimedia .

This country (Australia) relies heavily on Chinese trade. I wonder how much, if any, influence our Government would be prepared to exert…

Good question. But the Chinese government has often seemed pretty resistant to international pressure on its human rights record, and I can’t see it buckling to such pressure on this broad issue of censorship. But that’s just an opinion…

Oh Heather, such fun! We’re still blocked — timed out. So I tried the Chinese search sites. Weibo got no results. Baidu got: “Sorry, did not find the URL, you can directly access lastwordonnothing.com” Or as they said, “抱歉,没有找到该URL,您可以直接访问 lastwordonnothing.com.” Either way, what it means is unclear. Baidu went on to link to sites that linked to LWON, which I know because I tested one. Baidu was obsessed with Tom’s dinosaur chicken post.

Ann: I love the Baidu reply: it’s classic doublespeak. It’s like the Google browser saying to us, we’re not going to give you the URL for the site that you were searching for, but if you already have the URL go ahead and try it. But of course, then site is blocked. Orwell would appreciate this.

I wonder if China is blocking or throttling whole groups of sites hosted by US-based companies. They can’t be checking every tiny site, but they can put IP addresses from JustHost or goDaddy on a list. You may not have anything they care about, but other sites hosted by your provider might. (Of course, if one of you has set up your own server and is running the blog off of that, this is a moot point.)

Hi Sarah: I think the mass blocking or throttling idea is very likely. Just as my Sinologist friend noticed that he couldn’t access a large number of blogspot blogs this week –a fact I confirmed by looking at the list of blocked sites registered at greatfire.org–I think it’s possible that the censors are now blocking many wordpress blogs. Ours is hosted at a large commercial hosting service highly recommended by WordPress on its website, so it’s a safe guess that there are a lot of WordPress blogs there. Perhaps the censors decided to block all sites from that service as a way of curtailing free speech. But I don’t have a clue how to check that.

My web site made the black list when I published a short review of a book I had read about the Dalai Lama. I’m pretty sure once you have offended them, you are never forgiven. 🙂

I don’t doubt that David, and very few things rile the Chinese government as much as the Dalai Lama does. By the way, I just received word from my Sinologist friend this morning that Wikipedia is now fully and decisively blocked.

This just proves that what the Chinese government fears most in the world is it’s own people. Sad.

Hmmm.. the UN declared internet access a human right: http://www.wired.com/threatlevel/2011/06/internet-a-human-right/ . I realize it was in reaction to France and the UK and, to a lesser extent Syria, but it might apply, no?