This post originally appeared in December of 2019

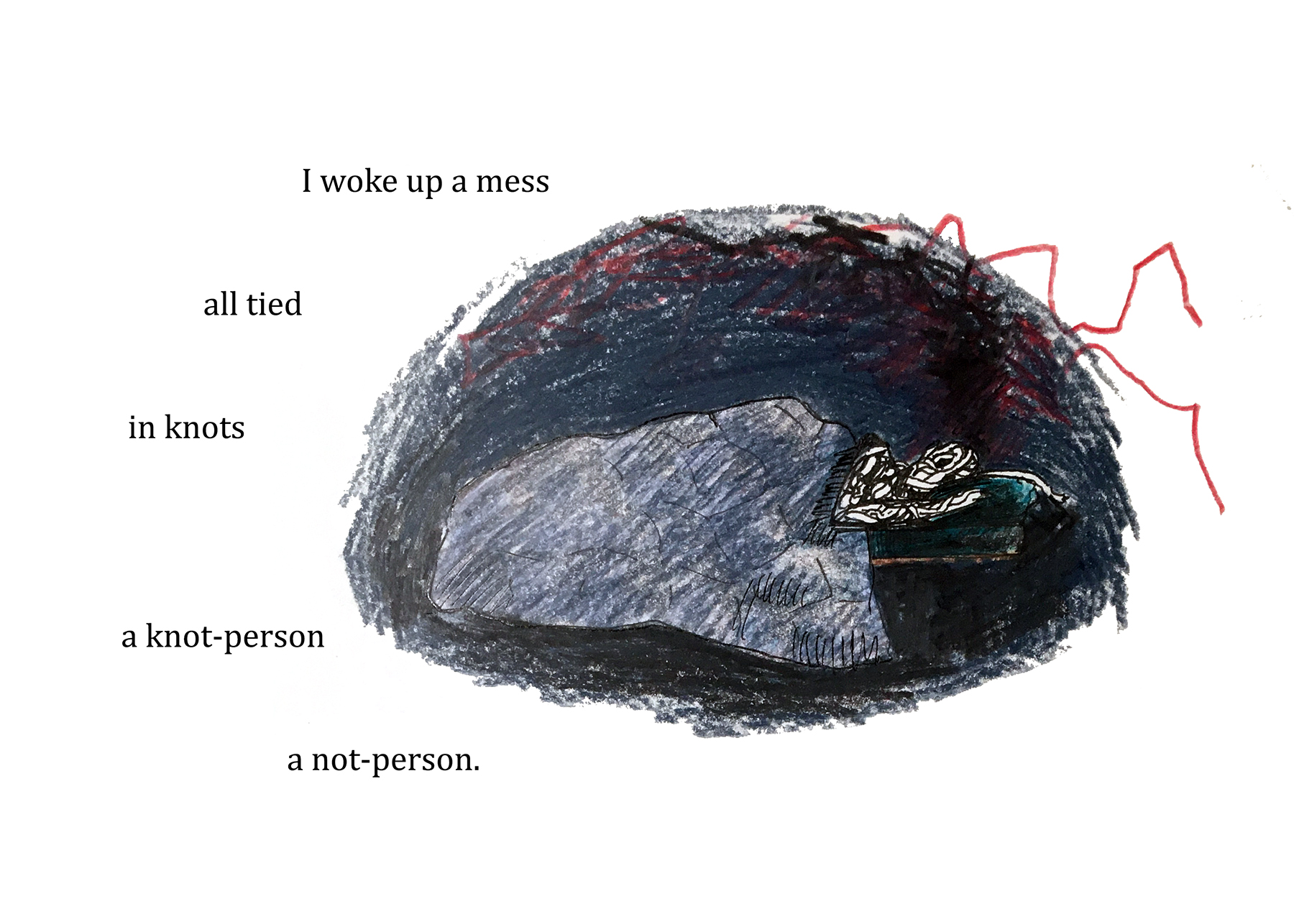

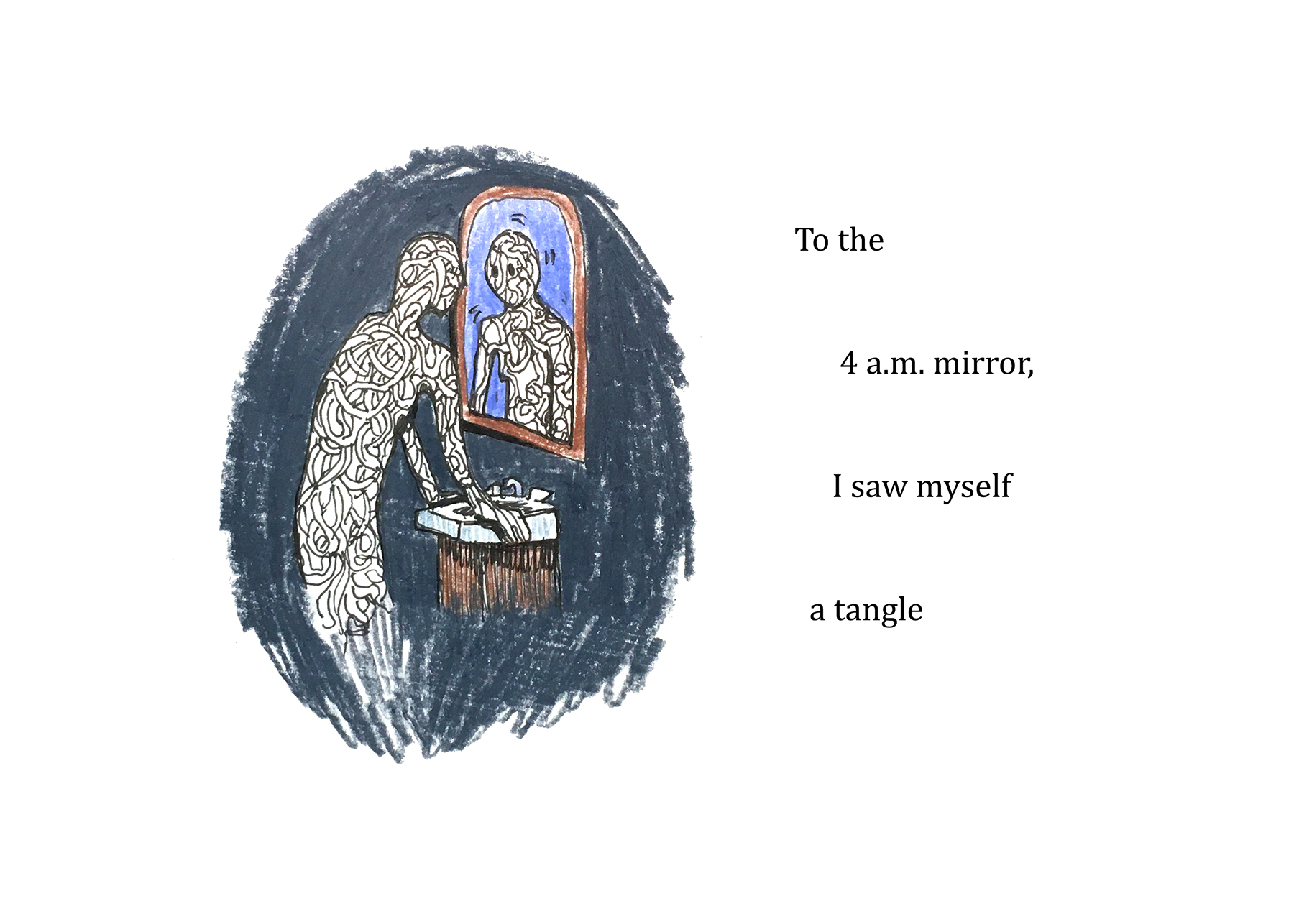

Some things are sisters, if you know how to look at them

like

a wildfire sun and a new penny

like

snowy boughs and salamander feet

Continue reading

Usually, summer is the season for hiking, weddings, family vacations, and neglecting my houseplants and backyard. I’m used to coming home after 10 days away to parched calathea and a lawn full of dandelions. But this year, being home all the time means I am taking special care of my plant friends, because what does it say about me if I can’t keep them alive when I no longer have an excuse for my usual carelessness?

In return, they’ve taught me some things.

Continue readingThis post originally ran winter of 2014 and circumstances have not changed. Careful out there!

There’s been a lot of road kill on my drive to work and back in Western Colorado, mostly prairie dogs and rabbits, and young magpies trying to learn how fast they have to fly to get out of the way. I find myself slowing and dodging for the live ones who continue shooting across my path like meteorites, or those who congregate near the yellow line, scattering in all directions at the last second.

The automobile is an act of violence. Never mind the incredible human toll taken by accidents where in the US about 100 people are killed every day, a whole other class of fatalities exists among those who aren’t even signed onto this culture of speed.

Stains and scraps of animal remains I race past every day leave me thinking about the ease of extinction, how even our rudimentary task of transportation leaves trails of entropy. Cottontails and prairie dogs, at least in my rural neighborhood, are not at risk of extinction, but a debt is being accrued. Continue reading

Less than a week after my eight-month-old started daycare, he spiked a fever. No big deal, I told myself. Maybe he was teething. Maybe he had picked up a cold. I tried not to spin out thinking about the third possibility. Babies get fevers all the time. COVID seemed like the least likely explanation.

Continue reading

I have some new neighbors who many people would consider a nuisance. They show up at random times. They occasionally kick the rocks that line my driveway, and once they knocked off my downspout. They also eat garbage and leave a real mess.

These neighbors are mostly loners. They watch me, unblinking, and do not approach or say hello. Sometimes they run away at the sight of me, but usually they just look in my direction, make eye contact, sniff the air and then move along. I don’t view this as unfriendly, because I don’t want to meet them face to face, either.

You can tell from the photo that these neighbors are bears. But I still feel compelled to write about them as if you don’t know this, because I myself am still shocked by the fact of their existence. I have neighbor bears, at least seven of them, plus five cubs. They were here first. This is their home. I am the intruder here, and yet they watch me and tolerate me so patiently. They are teaching me so many things.

Continue reading

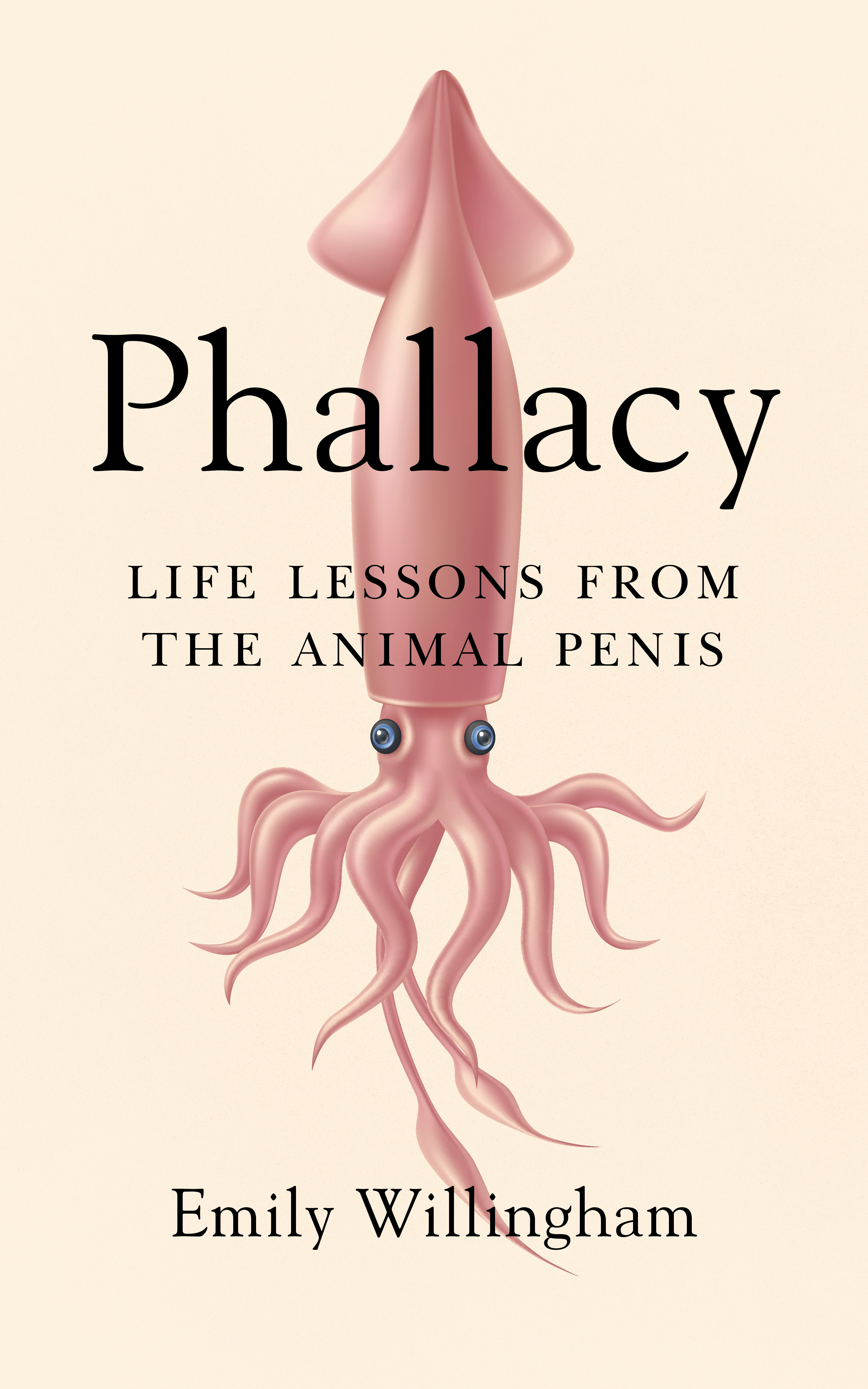

When I was in college my department offered a course in comparative anatomy. The idea was that you could learn a lot by comparing and contrasting different species. I was reminded of that course while reading Emily Willingham’s new book, Phallacy: Life Lessons from the Animal Penis, which is published tomorrow. The book offers a hilarious, enlightening and thought-provoking tour through the world of animal penises, but in the end, I can’t help thinking that the species we learn the most about is humans.

Emily is a friend of mine, and I’ve long admired her excellent work, so I was thrilled to receive an advance copy of her book. I invited her to LWON to talk about Phallacy and how she pulled it off.

Christie: What was the genesis of this book? How did you end up writing a book about animal penises?

Emily: I was working with my agent on an idea about the brain (which is now a book in progress) when I realized, somehow not having done so before, that I know a lot about penises. Not just from being around them, but as someone who did a postdoc in urology. So I sent her a quick email to that effect, and we were on the phone within the hour. It was amazing how fast it unfolded after that.

Christie: In the book’s introduction, you write about a childhood experience where a gardener at your grandmother’s house laid in wait for you, then got your attention and pulled down his pants and started masturbating. “He gestured to me, leering and threatening, trying to get me to come over to him,” you write. You were 12 and his behavior scared you, but you write that “He terrorized me, not his penis.” This seems like a running theme in the book: the consequence of our culture’s fixation on penises. Can you say a few words about the conflation of penises and masculinity?

Emily: Masculinity is a fluid concept, constrained and defined by sociocultural context. What is considered masculine is not the same across cultures, and what one culture might emphasize a lot can get little attention in another. That’s because people are so behaviorally and temperamentally variable from one person to the next, and culture changes over time and under different environmental influences. The human penis, on the other hand, is an anatomical structure that does not show this variability and complexity even in its function and is not a unique qualifier of masculinity. It is reductive to focus only on the penis as something that defines, categorizes, or damages a human being when our brains are the responsible parties.

Continue reading

I went up to a rock art panel in southeast Utah the other day, one known as the Desecration Panel. The sandstone wall is long and repeatedly marked by petroglyphs of animals and human-like characters about 1,500 years old, what is called Basketmaker tradition. Several are terribly defaced, the damage relatively recent. One figure, which once looked like those to either side, has been transformed into a monster of its former self, rising from the rock as if the past were not over, no sharp line saying when it wraps up and the present begins.

Stories vary, but this panel was altered by a hatchet in the 1950s or 60s. You could call it vandalism, but that is too simple a term. The act was highly intentional, perhaps desperate. The most reputable sources tell of an illness that struck Navajo families around the middle of the last century. They went to a medicine man who said the solution was defacing this rock art, taking out certain figures. They must have been connected to the illness, having some bearing on it, an echo or a power from long ago.

A friend was with me at the panel, John Tveten, an ER doctor who works the Navajo Reservation in Arizona. His region is ramping down from being one of the more severe coronavirus hotspots in the country. Tveten said he hadn’t had to intubate anyone from the virus for the past week, a big change. He showed up straight off his shift, a plunge into the desert.

Continue reading