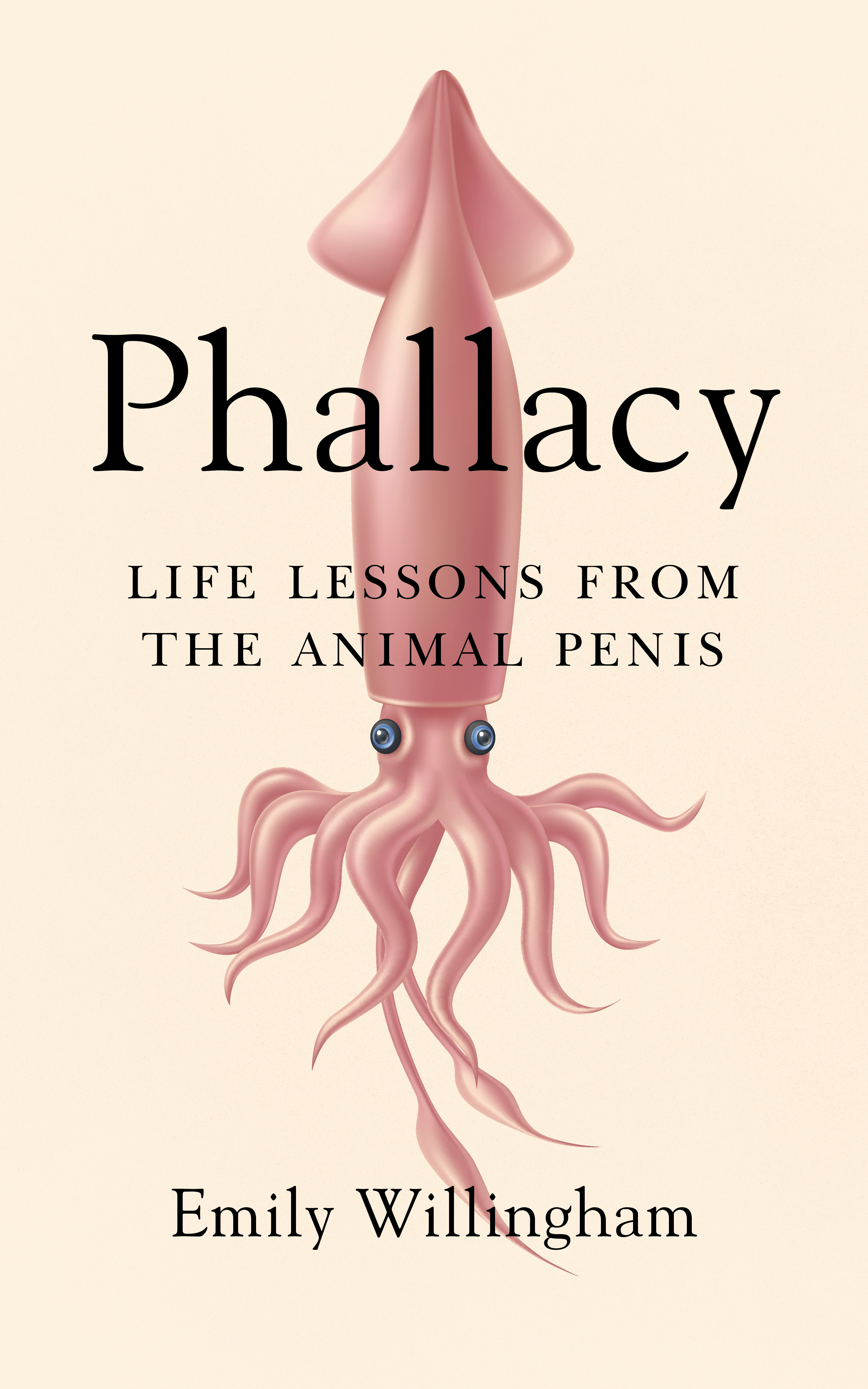

When I was in college my department offered a course in comparative anatomy. The idea was that you could learn a lot by comparing and contrasting different species. I was reminded of that course while reading Emily Willingham’s new book, Phallacy: Life Lessons from the Animal Penis, which is published tomorrow. The book offers a hilarious, enlightening and thought-provoking tour through the world of animal penises, but in the end, I can’t help thinking that the species we learn the most about is humans.

Emily is a friend of mine, and I’ve long admired her excellent work, so I was thrilled to receive an advance copy of her book. I invited her to LWON to talk about Phallacy and how she pulled it off.

Christie: What was the genesis of this book? How did you end up writing a book about animal penises?

Emily: I was working with my agent on an idea about the brain (which is now a book in progress) when I realized, somehow not having done so before, that I know a lot about penises. Not just from being around them, but as someone who did a postdoc in urology. So I sent her a quick email to that effect, and we were on the phone within the hour. It was amazing how fast it unfolded after that.

Christie: In the book’s introduction, you write about a childhood experience where a gardener at your grandmother’s house laid in wait for you, then got your attention and pulled down his pants and started masturbating. “He gestured to me, leering and threatening, trying to get me to come over to him,” you write. You were 12 and his behavior scared you, but you write that “He terrorized me, not his penis.” This seems like a running theme in the book: the consequence of our culture’s fixation on penises. Can you say a few words about the conflation of penises and masculinity?

Emily: Masculinity is a fluid concept, constrained and defined by sociocultural context. What is considered masculine is not the same across cultures, and what one culture might emphasize a lot can get little attention in another. That’s because people are so behaviorally and temperamentally variable from one person to the next, and culture changes over time and under different environmental influences. The human penis, on the other hand, is an anatomical structure that does not show this variability and complexity even in its function and is not a unique qualifier of masculinity. It is reductive to focus only on the penis as something that defines, categorizes, or damages a human being when our brains are the responsible parties.

Continue reading →