This post originally appeared on October 5, 2020. It felt especially prescient as this clusterfuck of a year ends. May we all untangle the knots of ourselves and find ways to rise into a new and better 2021.

This post originally appeared on October 5, 2020. It felt especially prescient as this clusterfuck of a year ends. May we all untangle the knots of ourselves and find ways to rise into a new and better 2021.

Thank goodness for ravines that are inconvenient to build on. This one cuts through the suburbs near my parents’ house. You can hear the Beltway from the spot where I took this picture, but the deer wander by anyway, and the squirrels, and the occasional human.

Photo: Helen Fields

This spring, after weeks of quarantine, my husband was probably already sick of me when I started reading about cicadas. As I ventured further into a Wikipedia wormhole, I shared with him the most interesting tidbits. “Did you know there are multiple broods?” I asked, as he played a game on his phone on the couch next to me. Thirty minutes later and 200 facts later, he’d moved into another room, but I was still shouting things like, “oh my god, there’s a guy who plays clarinet solos with cicadas as the accompaniment!” Finally, he came back into the living room to tell me: “I’m sorry, but I would like to unsubscribe from Cicada Facts.”

More recently, an editor of mine recalled at a meeting that when I was working on a story about COVID’s effect on lottery sales, I messaged her Lotto Facts on Slack. (According to a 2019 report from Oregon Lotto, over $7 million went unclaimed that fiscal year!) And while she didn’t seem to mind it (I’m sorry, Emily!), I felt a little mortified that this is apparently just what I do to the people in my life.

So, fine readers of LWON, you, too, will now be subjected to Jane Facts™, brought to you by looking through some of my recent Google searches. Some of these things you might already know; most are only mildly interesting, at best, but I hope there’s at least one new thing here that sparks excitement.

It is a Gamble tradition that each child can select one present to open on Christmas Eve, ahead of the Christmas Day onslaught. On a nature ramble yesterday with my father and me, my son asked if he could open his when we got back to the house, around 2pm.

“Christmas Eve,” says I. “The clue is in the name.”

“Christmas Eve is the day before Christmas,” says he. “Eve just means before something. For example, ‘Evening’ means ‘before night’. ‘Eve’-‘ning’.”

“’Twas the ning before Christmas,” says I. “….hmm, that doesn’t sound quite right.”

I am used to such lawyering from my firstborn. The joke used to be that he would grow up to be a children’s rights lawyer. But in that moment I realized that many children are just that—little Ruth Bader Ginsburgs shifting the bars of their cages ever so slightly—and that the gains they make can actually build on those that have been made by children before them.

Because who negotiated that rule that children can open just one present on Christmas Eve? It’s a sure bet that wasn’t a parent’s idea. That rule has the distinct flavour of a wheedling child, a Gamble of past generations wearing down her mother, not suspecting her sons and grandsons would be opening presents on Christmas Eve right into the 21st century, harvesting the fruits of her efforts.

So parents, before you give in to the next incremental change, consider this: your descendants down the line may be eating that extra piece of chocolate cake into eternity. Choose wisely.

p.s. I said yes.

The first recorded sighting of the strange birds occurred in August. A man posted a picture on my Facebook neighborhood group: Plump, chicken-esque body. Red beak. Black-and-white striped wings. Bandit mask over the eyes. Commenters were quick to ID the bird. Definitely a chukar. More photos revealed there were at least five roaming the streets. My neighbors were instantly smitten. “May we keep them?” one woman asked. “I love them.”

Continue reading

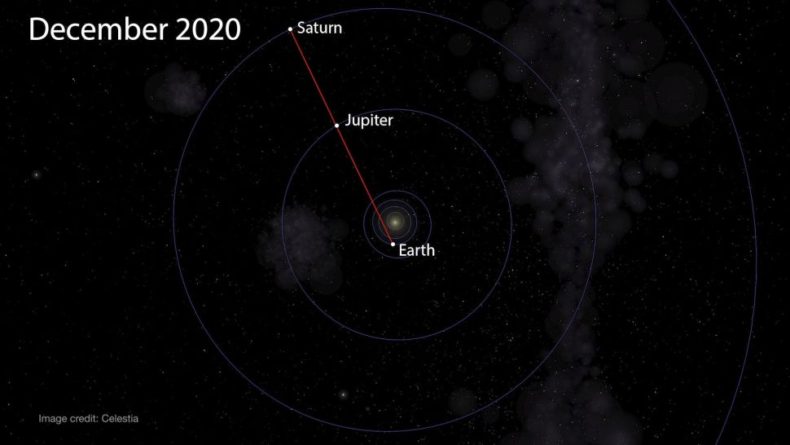

In this year of darkness, today brings something to celebrate. Winter solstice is the shortest day of the year, which means the light will finally start returning. And this year, the first day of winter also marks a special celestial event — the Jupiter-Saturn Great Conjunction.

Imagine that our solar system is a racetrack, and each of the planets is a runner circling the sun in their own lane, with the Earth toward the center of the stadium, Henry Throop, a NASA astronomer, said in an explainer. “From our vantage point, we’ll be able to see Jupiter on the inside lane, approaching Saturn all month and finally overtaking it on December 21.”

It’s been almost 800 years since Saturn and Jupiter were this close in our sky and not too near to the sun or low in the sky to be seen by most Earthlings. Saturn is much dimmer than Jupiter, because it’s smaller and almost twice as far away, but their paths through our sky will make them appear so close from our vantage point so as to almost appear as one.

Poets may find metaphors or deeper meaning in this fortuitous alignment of the planets, but from a scientific perspective it’s simply a cool demonstration of geometry and our place in the Milky Way relative to these two neighbors.

I’ve been observing the two bright planets all year, watching them slowly converge. Last Thursday, I went for a run at sunset and as the sky went from shades of pink and red to deep blue turning to black, the bright glow of Jupiter and Saturn put on a show in the southwest sky.

I’m writing this on Sunday night (12/20) and this evening after sunset I spent some time looking at the two planets. Saturn and Jupiter are still distinct, both with the naked eye and through low powered binoculars. Tonight, they will almost converge when observed from Earth. (According to Joe Rao at Space.com they probably still won’t look like a single point, at least not to people like me with good eyesight. But they will still look really cool!)

One of my favorite things about living in the rural West is looking up at the dark sky. I once stayed up most of the night with my friend Rosemerry, gazing at the sky full of of stars overhead and pondering our place in this vast universe. It’s a thing I can’t get enough of — that feeling of being totally at home in my surroundings while also sensing the wondrous expanse beyond my native planet.

I can’t wait to get more of that tonight, and I hope you will too. The two planets are bright enough to be seen without any aid, but if you live in a very light city or are unlucky enough to have cloudy skies tonight, the Lowell Observatory is hosting a livestream of the event on YouTube, which you can watch here.

Images:

Photo of Jupiter and Saturn over the landscape of the Sacred Mountains of Gran Canaria by Starry Earth, via Flickr.

Diagram of Jupiter, Saturn and Earth from NASA.

Just down the road from my house, there lived a bull. He had a massive, muscular neck and a glossy black coat that rippled as he strode around the pear orchard that served as his pasture. In fall, when the pears ripened, the bull rubbed against the old trees, shaking their trunks until the fruit fell to the ground. Other animals came to eat pears too; wild turkey, geese, and deer. But the bull was my favorite to watch, so fat and majestic.

One day it occurred to me that the trees were so full of pears that the bull could never eat them all. For a moment I contemplated what might happen if I (ever so quickly and quietly) jumped over the fence to grab one.

As if reading my thoughts, the bull lifted his enormous head and fixed me with his inscrutable brown eyes. I froze. Would he charge? Would I get smushed? Maintaining eye contact, he rubbed his enormous flank against a pear tree, using so much of his weight I thought he might snap the tree in half. Pears fell by the dozen, thumping in the dirt around him. As the bull bent his neck to the ground, picked up a pear, and started to chew, he held my gaze, seeming to ask:

“Do you know who I am, mortal?”

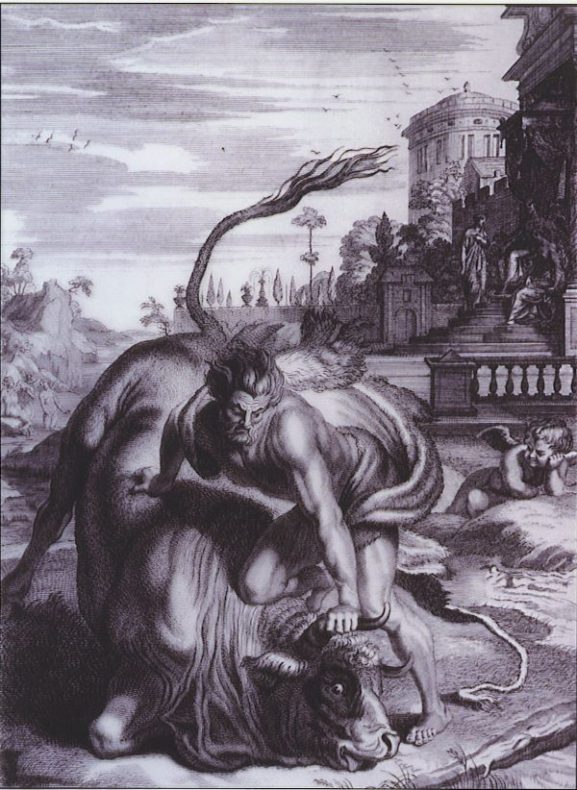

Humans have worshipped bulls in various forms for more than 10,000 years, when they first domesticated bos taurus. There’s the humped white bull Nandi, beloved vehicle of the Hindu god Shiva; Apis, a fertility god of Egypt; the Bull of Heaven, from the Epic of Gilgamesh. In one creation myth from ancient Iran, the bull was the first animal; in a Christ-like parallel, the sacrifice of his blood and flesh renews the world.

Humans being humans, they’ve also used bulls as symbols of control and brute force (see Zeus and the rape of Europa; Minotaur the man-eater; the Wall Street Bull; the bulldozer.) When the Pope wants something done, he writes a papal bull, sealed by the bubble of official papal wax known as a bulla.

One of my favorite bull stories, The Story of Ferdinand, is about a young Spanish bull who does not enjoy fighting, but prefers to sit under a cork tree and smell the flowers. The simple power of Ferdinand’s story, I think, is that it unravels the old conflation of male strength and violence, revealing such macho projections for what they really are: bullshit. (Disliking what he deemed its pacifist message, Hitler ordered the book to be burned.)

In 2009, a red and white Hereford named Dominette became the first cow to have its genome sequenced; since then, the cattle industry has invested millions in efforts like the 1000 Bull Genomes Project, which aim to optimize the modern bovine from rump to udder. Last year several outlets reported that nearly all US dairy cows are descended from just two bulls, dangerously narrowing their genetic diversity. Today, most bulls are owned not by small farmers but by genetics companies; the San Diego firm Illumina promises that their patented genetic screen, the BovineHD Genotyping BeadChip, will ensure cows with “exceptional tenderness” and “better marbling.”

Breed success, their brochure croons. Join the revolution.

A few weeks ago I noticed that the bull next door was gone, along with all the cows in the orchard. I’ve never met the neighbors who keep him, but even in normal times I’d have had to screw up a fair amount of courage to walk up their long driveway and ask where they took him. It would sound a bit odd under the best of circumstances — Hello, I’ve been watching your house, where is the bull? –but it feels odder than usual, wearing my mask, to knock on a stranger’s door and ask after their livestock.

“Where do bulls go in winter?,” I typed into Google instead, fearing that after fattening himself on autumn pears, the bull had been sent to the slaughterhouse. Thankfully, I learned his owners have probably just moved him somewhere warm, to protect his valuable, vulnerable testicles from frostbite. Scrotal frostbite is a serious threat to bull fertility, not only damaging the quality of semen, but a bull’s desire to mate, I learned: In one study, Beef magazine reports, “some refused to service cows for six months following the blizzard.”

Every morning now, I look at the ice crystals sparkling on the empty pear orchard, and hope the bull is cozy in a barn somewhere, wearing a thick winter coat reminiscent of his wild predecessor Bos primigenius, the auroch.

Wherever he’s gone, I hope someone is appreciating his majesty and mystery, and not just his meat or his gonads. I wish I could trace his head in graceful sweeps of red chalk, like the cave painters of Lascaux, or carve his bust out of serpentine and mother of pearl, like the Minoan sculptors of the Bull’s Head rhyton. Instead, I built this tiny version out of modeling clay, a talisman until the bull returns.

Recently Ann wrote that, in the pandemic, she’d been paying attention to “the world that exists when I’m not noticing it, the world that goes on about its own business.”

The other day, the world did something fantastic. It passed through the dust from an asteroid, giving us the Geminids. This is apparently one of the better meteor showers, but I’d never paid attention to it before. Who goes and stares at the sky outside when it’s cold? Not me.

But this weekend I heard the Geminids were coming, and it was going to be clear, and this year I’ve decided I have to put up with cold if I ever want to see my friends in person, so I suggested to a friend that we go chase them. She has a warm coat, so she agreed, and my parents agreed too, so all of us sat in the cold in a field behind a middle school in the suburbs, waiting for pieces of dust to burn.

Continue reading