Just down the road from my house, there lived a bull. He had a massive, muscular neck and a glossy black coat that rippled as he strode around the pear orchard that served as his pasture. In fall, when the pears ripened, the bull rubbed against the old trees, shaking their trunks until the fruit fell to the ground. Other animals came to eat pears too; wild turkey, geese, and deer. But the bull was my favorite to watch, so fat and majestic.

One day it occurred to me that the trees were so full of pears that the bull could never eat them all. For a moment I contemplated what might happen if I (ever so quickly and quietly) jumped over the fence to grab one.

As if reading my thoughts, the bull lifted his enormous head and fixed me with his inscrutable brown eyes. I froze. Would he charge? Would I get smushed? Maintaining eye contact, he rubbed his enormous flank against a pear tree, using so much of his weight I thought he might snap the tree in half. Pears fell by the dozen, thumping in the dirt around him. As the bull bent his neck to the ground, picked up a pear, and started to chew, he held my gaze, seeming to ask:

“Do you know who I am, mortal?”

Humans have worshipped bulls in various forms for more than 10,000 years, when they first domesticated bos taurus. There’s the humped white bull Nandi, beloved vehicle of the Hindu god Shiva; Apis, a fertility god of Egypt; the Bull of Heaven, from the Epic of Gilgamesh. In one creation myth from ancient Iran, the bull was the first animal; in a Christ-like parallel, the sacrifice of his blood and flesh renews the world.

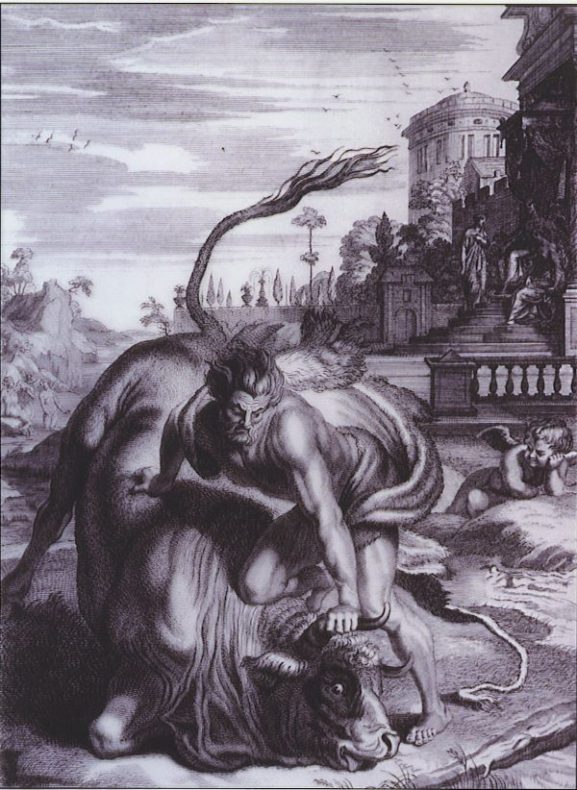

Humans being humans, they’ve also used bulls as symbols of control and brute force (see Zeus and the rape of Europa; Minotaur the man-eater; the Wall Street Bull; the bulldozer.) When the Pope wants something done, he writes a papal bull, sealed by the bubble of official papal wax known as a bulla.

One of my favorite bull stories, The Story of Ferdinand, is about a young Spanish bull who does not enjoy fighting, but prefers to sit under a cork tree and smell the flowers. The simple power of Ferdinand’s story, I think, is that it unravels the old conflation of male strength and violence, revealing such macho projections for what they really are: bullshit. (Disliking what he deemed its pacifist message, Hitler ordered the book to be burned.)

In 2009, a red and white Hereford named Dominette became the first cow to have its genome sequenced; since then, the cattle industry has invested millions in efforts like the 1000 Bull Genomes Project, which aim to optimize the modern bovine from rump to udder. Last year several outlets reported that nearly all US dairy cows are descended from just two bulls, dangerously narrowing their genetic diversity. Today, most bulls are owned not by small farmers but by genetics companies; the San Diego firm Illumina promises that their patented genetic screen, the BovineHD Genotyping BeadChip, will ensure cows with “exceptional tenderness” and “better marbling.”

Breed success, their brochure croons. Join the revolution.

A few weeks ago I noticed that the bull next door was gone, along with all the cows in the orchard. I’ve never met the neighbors who keep him, but even in normal times I’d have had to screw up a fair amount of courage to walk up their long driveway and ask where they took him. It would sound a bit odd under the best of circumstances — Hello, I’ve been watching your house, where is the bull? –but it feels odder than usual, wearing my mask, to knock on a stranger’s door and ask after their livestock.

“Where do bulls go in winter?,” I typed into Google instead, fearing that after fattening himself on autumn pears, the bull had been sent to the slaughterhouse. Thankfully, I learned his owners have probably just moved him somewhere warm, to protect his valuable, vulnerable testicles from frostbite. Scrotal frostbite is a serious threat to bull fertility, not only damaging the quality of semen, but a bull’s desire to mate, I learned: In one study, Beef magazine reports, “some refused to service cows for six months following the blizzard.”

Every morning now, I look at the ice crystals sparkling on the empty pear orchard, and hope the bull is cozy in a barn somewhere, wearing a thick winter coat reminiscent of his wild predecessor Bos primigenius, the auroch.

Wherever he’s gone, I hope someone is appreciating his majesty and mystery, and not just his meat or his gonads. I wish I could trace his head in graceful sweeps of red chalk, like the cave painters of Lascaux, or carve his bust out of serpentine and mother of pearl, like the Minoan sculptors of the Bull’s Head rhyton. Instead, I built this tiny version out of modeling clay, a talisman until the bull returns.

5 thoughts on “Bos Taurus”

Comments are closed.