This post first ran on January 15, 2013, but since then, the New York Times ran a gorgeous photo spread of murmurations that you should definitely check out.

This morning I awoke to the kind of day that offers an easy excuse to skip the walk. The temperature gauge read -3F (-19C) when I crawled out of bed, and by the time I’d finished the tea and hot porridge my husband had prepared, it was still only -1F. But the dogs were eager, the sun was shining, and my day never feels quite right without our morning ritual.

And so we pulled on our snow boots, bundled up and headed out the door. The snow was squeaky cold, and the air had a briskness that put a hustle in our strides. Halfway up the hill to the lookout, a loud ruckus. Dave turned to me. “Stop. Shhhh…” We looked at each other. “Hear that?” A lush symphony of bird song. Starlings, from the sound of it. But where?

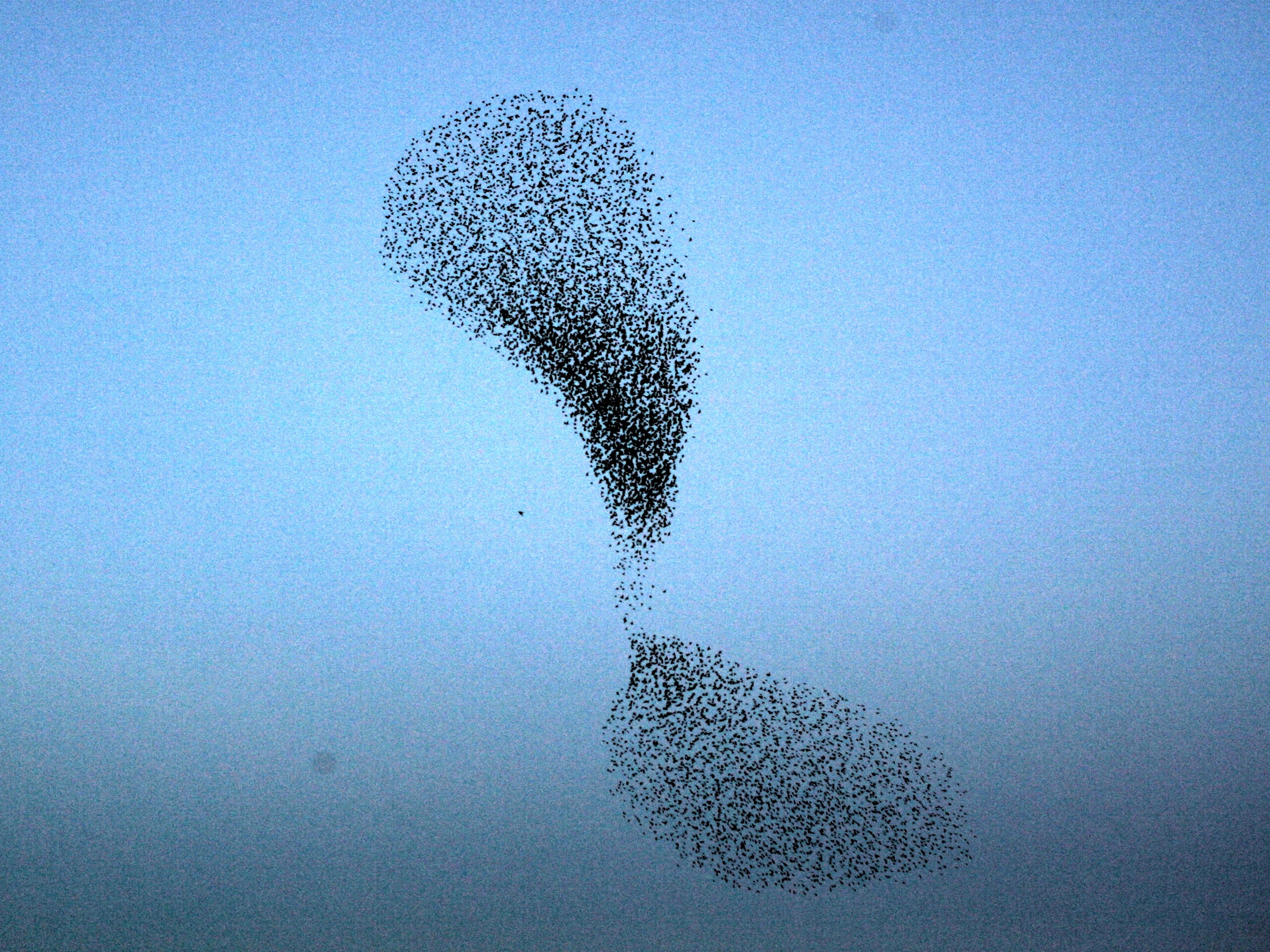

We looked skyward. Nothing. Upslope, only a crow in a nearby piñon pine. Then I spotted them in our neighbor’s willow trees down below. Starlings, yes. Hundreds of them. The moment I pointed to them, as if on cue, they rushed skyward in unison. The birds formed a rising crescendo, then swooped down, and then up and across the sky, like a ribbon, wrapping around itself.

If nature has ever produced a more perfect thing than the mesmerizing beauty of this starling swarm, I have yet to encounter it. No other phenomenon has ever stopped me in my tracks quite like this, made me forget everything else in the world except the brief moment of grace unfolding before me.

A flight of starlings in concert is called a murmuration. Murmuration–even the name is poetic.

Scientists aren’t entirely sure why murmurations happen. But they have some theories. Hawks and falcons prey on starlings (and also my chickens this time of year), and one theory holds that murmurations provide a way for starlings to monitor predators. The chaotic, but graceful motion of a murmuration might also help to confuse and deter predators. As a paper published last year explains,

Work in the 1970s showed that starlings in larger groups responded to the presence of a model hawk faster, and recent work has shown that the formation of ‘waves’ in murmurations is linked to reduced predation success by peregrine falcons. Waves propagate away from an attack, and so fluctuations in the local structure are likely also to be efficient in confusing potential predators.

But even more fascinating to me than why they murmurate is how they pull it off. Here, the European Commission-funded project STARFLAG has some answers. Researchers at STARFLAG have studied starlings around Rome and found that birds in the flock don’t worry about all of the hundred or more birds in the flock. Instead, they focus on six or seven of their neighbors and synchronize with them.

Such synchronicity is a sight to behold. If poetry has a physical presence, this is it. Birds, moving this way and then—suddenly—that. Up, and then down and just as you think you have their flight path figured out, they veer here and then there, always with grace and with fluidity.

This morning’s murmuration was unexpected, and then, just like that, it was over. The starlings landed on some juniper trees on the hillside below us and we continued our trek to the lookout. All the while we kept watch on those trees, but the starlings remained motionless, at least for the moment. The second swarm didn’t materialize during our walk, but the joy of the murmuration stayed with me throughout the day. As tethered as I was to the virtual world later in the day, I could not escape the connection to the physical environment that I’d formed in those brief minutes of bliss.

*Image courtesy of Andrea Cavagna at the STARFLAG Project.