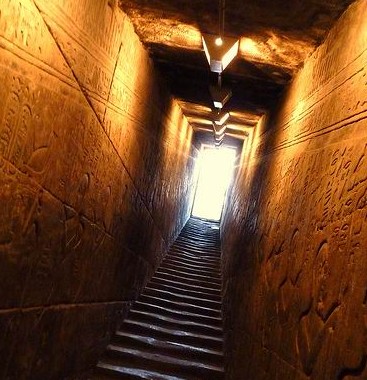

Most archaeologists I know have a soft spot for Indiana Jones. They might not admit it. They might grimace at the famous bullwhip and guffaw at all the suspension-bridge antics over crocodile-infested waters. But despite that, or perhaps because of it, Indiana Jones often captures something from a defining moment in their lives. It reminds them—as little else can—of childhood and their Howard Carter/Gertrude Bell dreams of becoming archaeologists, of going it alone, of mastering ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, of roaming faraway deserts and discovering the golden treasures of ancient kings. Could anything that adults do be more fun?

Most archaeologists I know have a soft spot for Indiana Jones. They might not admit it. They might grimace at the famous bullwhip and guffaw at all the suspension-bridge antics over crocodile-infested waters. But despite that, or perhaps because of it, Indiana Jones often captures something from a defining moment in their lives. It reminds them—as little else can—of childhood and their Howard Carter/Gertrude Bell dreams of becoming archaeologists, of going it alone, of mastering ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, of roaming faraway deserts and discovering the golden treasures of ancient kings. Could anything that adults do be more fun?

At the end of this month, Montreal Science Centre is hosting the world premiere of an exhibit entitled Indiana Jones and the Adventure of Archaeology. On display will be props and models from the George Lucas movies as well as some lovely ancient eye candy from the collections of the University of Pennsylvania Museum. The exhibit will surely draw huge crowds, including, I suspect, most archaeologists from the region.

What I find fascinating though is how little this childhood dream matches the very real, very adult pleasure of working in the field. It’s a pleasure that has little to do with adrenaline, and much to do with other kinds of human chemistry. Continue reading