I live in a bubble. Its name is San Francisco, a magical place where everyone recycles, no one smokes, and Nancy Pelosi is considered distressingly conservative. Worse, I teach environmental sustainability at Stanford, where I’m surrounded by bicycle riding, reusable mug toting, enthusiastically composting colleagues and students. I come from the outside world, so I know my current behavioral baseline is a little skewed. But still, I was recently reminded that some Americans continue to use incandescent light bulbs, and I was genuinely surprised.

I live in a bubble. Its name is San Francisco, a magical place where everyone recycles, no one smokes, and Nancy Pelosi is considered distressingly conservative. Worse, I teach environmental sustainability at Stanford, where I’m surrounded by bicycle riding, reusable mug toting, enthusiastically composting colleagues and students. I come from the outside world, so I know my current behavioral baseline is a little skewed. But still, I was recently reminded that some Americans continue to use incandescent light bulbs, and I was genuinely surprised.

A far bigger shock came, as they usually do, unbidden from the Internet. Continue reading

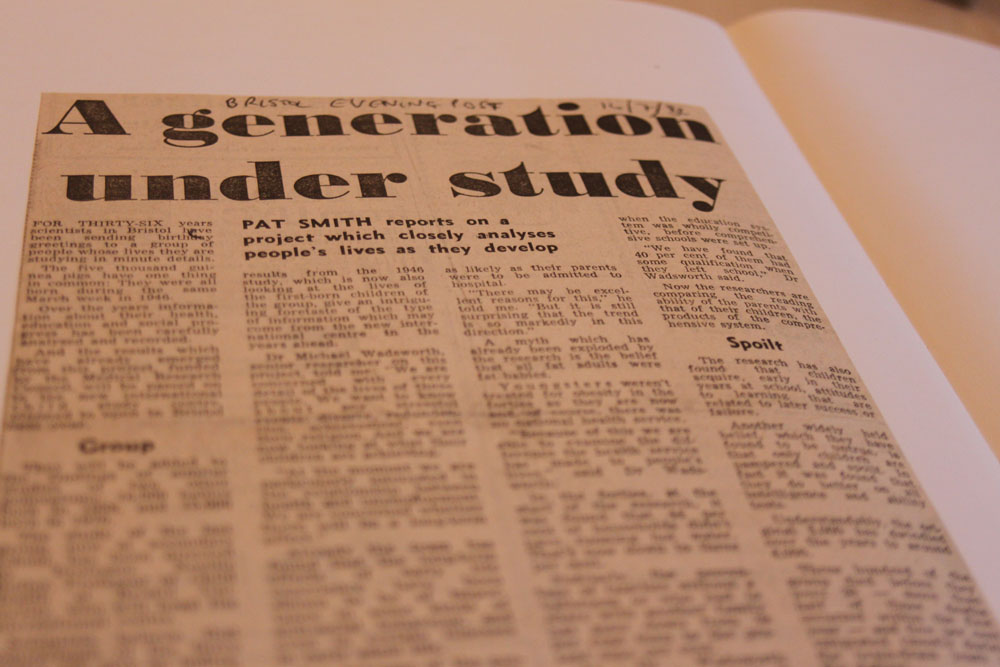

Britain in March 1946 was a dank, hungry, but optimistic place as people grappled with winter, rationing and the aftermath of World War 2. It was also the time that the country gave birth to something historically and scientifically remarkable. 13,687 babies born during one March week were weighed, measured and enrolled into what has, today, become the longest running study of human development in the world.

Britain in March 1946 was a dank, hungry, but optimistic place as people grappled with winter, rationing and the aftermath of World War 2. It was also the time that the country gave birth to something historically and scientifically remarkable. 13,687 babies born during one March week were weighed, measured and enrolled into what has, today, become the longest running study of human development in the world.