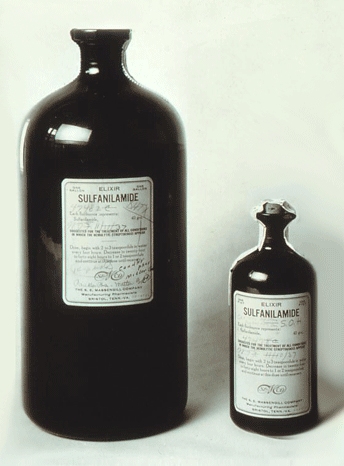

On September 27, 1937, Susie Mae DeLoach caught her leg on a strip of barbed wire. The wound festered, and the infection spread, eventually reaching her heart. None of the remedies DeLoach’s doctor recommended seemed to have any effect. And by the time her family called Dr. Johnston Peeples for a second opinion, she was gravely ill. Peeples prescribed a new medication—a sweet, ruby liquid called Elixir Sulfanilmide. DeLoach’s kidneys began to fail, and a little over a week later, she was dead.

On September 27, 1937, Susie Mae DeLoach caught her leg on a strip of barbed wire. The wound festered, and the infection spread, eventually reaching her heart. None of the remedies DeLoach’s doctor recommended seemed to have any effect. And by the time her family called Dr. Johnston Peeples for a second opinion, she was gravely ill. Peeples prescribed a new medication—a sweet, ruby liquid called Elixir Sulfanilmide. DeLoach’s kidneys began to fail, and a little over a week later, she was dead.

Others in the South were dying too—a farm laborer in Mississippi, a butcher in Tennessee, an eight-year-old boy in Oklahoma. More than 100 people died in the fall of 1937. They suffered from a variety of maladies, but all exhibited remarkably similar symptoms toward the end: vomiting and an inability to urinate. And all shared a common remedy—Elixir Sulfanilmide. Continue reading