On September 27, 1937, Susie Mae DeLoach caught her leg on a strip of barbed wire. The wound festered, and the infection spread, eventually reaching her heart. None of the remedies DeLoach’s doctor recommended seemed to have any effect. And by the time her family called Dr. Johnston Peeples for a second opinion, she was gravely ill. Peeples prescribed a new medication—a sweet, ruby liquid called Elixir Sulfanilmide. DeLoach’s kidneys began to fail, and a little over a week later, she was dead.

On September 27, 1937, Susie Mae DeLoach caught her leg on a strip of barbed wire. The wound festered, and the infection spread, eventually reaching her heart. None of the remedies DeLoach’s doctor recommended seemed to have any effect. And by the time her family called Dr. Johnston Peeples for a second opinion, she was gravely ill. Peeples prescribed a new medication—a sweet, ruby liquid called Elixir Sulfanilmide. DeLoach’s kidneys began to fail, and a little over a week later, she was dead.

Others in the South were dying too—a farm laborer in Mississippi, a butcher in Tennessee, an eight-year-old boy in Oklahoma. More than 100 people died in the fall of 1937. They suffered from a variety of maladies, but all exhibited remarkably similar symptoms toward the end: vomiting and an inability to urinate. And all shared a common remedy—Elixir Sulfanilmide.

Several companies were marketing sulfanilamide at the time, but most sold the drug as a powder or tablet. The newly discovered compound seemed to be a remarkably effective antibacterial. Sulfanilamide helped curb an outbreak of meningitis among the French Foreign Legion in Nigeria, and experiments in Maryland and Pennsylvania showed that it could also fight streptococcus infections and pneumonia. Perhaps the most ringing endorsement came in 1936, when sulfanilmide saved the life of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s son.

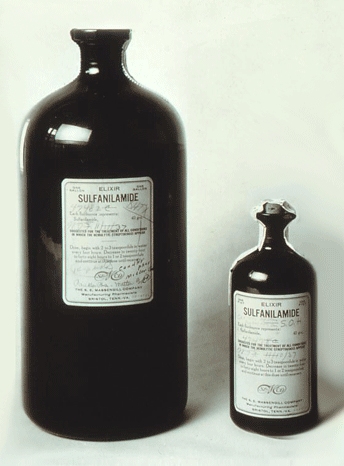

S.E. Massengill Company, a small drugmaker in Tennessee, thought there might be demand for a liquid form of the popular drug. “Sulfanilamide was a powder–and down south, if you can’t give colored people or children a red liquid medicine, you aren’t any kind of a doctor at all,” remarked one Food and Drug Investigator when he was interviewed about the incident in 1978. To create this red potion, Harold Cole Watkins, Massengill’s chief chemist, dissolved sulfanilamide in a solvent called diethylene glycol. Raspberry extract, saccharin, and caramel sweetened the concoction. Although the company tested its medicine for taste and appearance, it was under no obligation to conduct safety testing.

In September 1937, the company shipped out the first 240 gallons of its elixir. By mid-October, the American Medical Association (AMA) had received word of sulfanilamide-linked deaths in Oklahoma. AMA scientists requested samples of the drug and attempted to identify the toxic component. They administered pure sulfanilamide, pure diethylene glycol, and a combination of the two to rabbits, rats, and dogs. It didn’t take long to pinpoint the culprit: diethylene glycol, “a decidedly toxic substance and cumulative poison,” wrote one scientist.

The news came as a blow to Archie Calhoun, a physician in Mount Olive, Mississippi, who had prescribed the medicine to 13 patients. “Nobody but Almighty God and I can know what I have been through these past few days,” he wrote in a letter. “To realize that six human beings, all of them my patients, one of them my best friend, are dead because they took medicine that I prescribed for them innocently, and to realize that that medicine which I had used for years in such cases suddenly had become a deadly poison in its newest and most modern form, as recommended by a great and reputable pharmaceutical firm in Tennessee: well, that realization has given me such days and nights of mental and spiritual agony as I did not believe a human being could undergo and survive. I have known hours when death for me would be a welcome relief from this agony.”

In 1938, Congress passed the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, which required that drugs be proven safe before they reach pharmacy shelves. The requirement seems like a no-brainer. But it also seems obvious that drugs should be proven effective. However, that law would take another 25 years and require another tragedy—a spate of birth defects in Europe caused by the drug thalidomide.

Today, not much has changed. Tragedy is still a key driver of new regulation. In 2012, a shipment of contaminated steroid injections from a compounding pharmacy in Massachusetts caused a meningitis outbreak that killed 64 people and sickened more than 700. In 2013, lawmakers passed the Drug Quality and Security Act, which gives the Food and Drug Administration gives FDA new authority over compounding facilities. And earlier this year, 11 people in Los Angeles contracted a antibiotic-resistant strain of bacteria after undergoing endoscopic procedures. Just this month the FDA began asking manufacturers to submit data showing their scopes can be completely disinfected.

“Lawmakers are perpetually reactive. They spend years trying to develop fixes to past problems, in the hope that history will not repeat itself,” writes Joshua Mitts, a postdoctoral fellow at Columbia Law School. That may be the status quo, but is it the best we can do? Surely some of these problems could have been anticipated and avoided. Surely some of these lives could have been saved.

***

Image courtesy of Wikimedia commons

I first read about the Elixir Sulfanilamide disaster in Paul Offit’s excellent book, Do You Believe in Magic?

More great resources:

Taste of Raspberries, Taste of Death: The 1937 Elixir Sulfanilamide Incident (FDA)

Elixir Sulfanilamide: Deaths of 1937 (Pathophilia)

The Elixir Tragedy, 1937 (The Scientist)

There probably are countless regulations and people saving lives by making sure things are safe and properly done before a product is released. But how would you go about counting lives that weren’t lost? How do you know about disasters that were avoided? You don’t, because they didn’t happen, you only know about the stuff that goes wrong. Oh, and “everything went well and didn’t kill anybody” isn’t a great news headline either.

Good point, Neil.