I walked along the edge of a cliff. Under my feet, grass. To my right, a hundred-foot drop to the waters of the English Channel. A strong wind blew off the water and over the cliff, blowing the loose ends of hair in my face, obnoxiously. To my left was a field, planted with something I can narrow down to “a grain.” It was the second day of a week-long walk along a segment of the UK’s South West Coast Path, a 630-mile-long trail around the edge of the peninsula that makes up the southwestern corner of Britain.

High above the spring-green waves of grain was a skylark, twittering relentlessly. On the ground, a skylark isn’t a very memorable bird. It’s brown and streaky with a little crest of feathers on its crown. A skylark in the sky is still not much too look at: a madly-flapping speck against the cloudy white sky. While they hover and swoop, though, they emit a constant stream of notes. Because these are birds, I assume they’re showing off for females or announcing their territory or something. As my friends and I walked along, we passed from one skylark’s flapping-ground to the next, on and on above the cliffs. They sang and sang and sang. The skylark made me think of a lyric from a folk song: “Up flies the kite; down falls the lark-o.”

I know more English folks songs than the average American person, and probably more than the average British person, too. I sing in the Washington Revels, a community theater group that performs traditional material mostly from North America and Europe. Our annual spring show, the May Revels, is focused mostly on countryside traditions of England. We dance around the maypole. Some years we sing the song with the lark and the kite, a tradition from the village of Padstow, 70 miles due west of the cliff where I heard the larks.

May is a thrilling time of year wherever you are. In the English May we saw bluebells growing thick under white-barked trees. Primroses, sea pinks, forget-me-nots, and the unbeautifully-named golden dead nettle paved our way with flowers. The white globe-shaped blooms of some member of the onion family turned east-facing slopes of wooded valleys into a garlicky fairyland. Birds sang noisily everywhere we went.

Over and over songs that I knew popped into my head. The lark brought not only the Padstow song to mind, but also The Lark Ascending, by Ralph Vaughan Williams, who loved the English countryside even more than I do.

The English robin and the North American robin share a name, but ours is sturdy and largeish while the British one is a sweet, fat little bird with a little less red and a pretty dab of gray. In The Secret Garden, the bird that shows Mary Lennox the way into the garden is a robin, and I have always wanted one as a friend myself. I saw them often, perched on a fencepost or singing from the top of a bush, and almost always found myself singing the 500ish-year-old song “Ah Robin.” I’m pretty sure this song is about a dude named Robert, not a bird, but it came to mind anyway.

Swallows streaked by at fence-level, wings swept back like tiny fighter jets. “Bring back the roses to the dells/The swallow from her distant clime/The honeybee from drowsy cells,” I sang to myself.

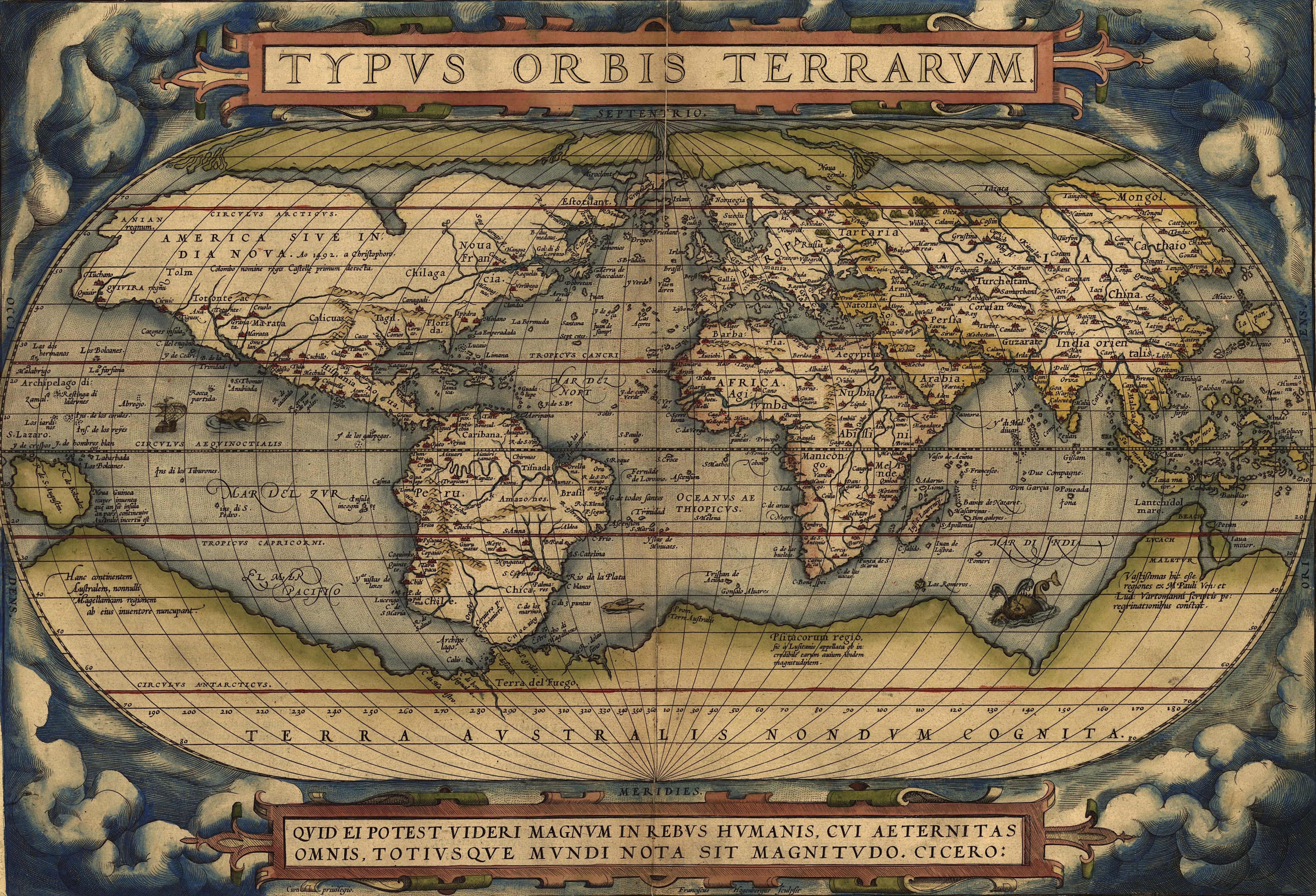

For the first time, I was seeing all of these birds in their ecological context. When I sing about the swallow and the honeybee, I’m thinking about the swallows and honeybees I know, but, in a way, these fields are what I’m unknowingly referring to. They’re about spring and landscapes that have been agricultural for centuries in a country on the other side of the sea.

By the way: England’s blackbird is a thrush, a different family from our creaking New World blackbirds. They sang from the bushes, too, and could only bring to mind one song.

Photo: Shutterstock

Correction: The original version of this piece said both the English robin and the American robin are thrushes, but apparently the English robin has been reclassified since my bird book was published, 20-some years ago.

When top LWONian Ann Finkbeiner asked if I would contribute a top-five list of something in honor of LWON’s fifth anniversary, I immediately said yes. Not just because I love and am a little afraid of Ann, but also because of a writerly phenomenon that she may already have coined a clever name for. It’s the mind’s tendency to go blank when deadlines loom and then start generating story ideas once no outlet exists. To wit, the following list of the top five posts I think Ann would have liked, if only they had occurred to me when I was still an active person of LWON:

When top LWONian Ann Finkbeiner asked if I would contribute a top-five list of something in honor of LWON’s fifth anniversary, I immediately said yes. Not just because I love and am a little afraid of Ann, but also because of a writerly phenomenon that she may already have coined a clever name for. It’s the mind’s tendency to go blank when deadlines loom and then start generating story ideas once no outlet exists. To wit, the following list of the top five posts I think Ann would have liked, if only they had occurred to me when I was still an active person of LWON: